Uncommon truths: Giving credit to China

Posted by Paul Jackson, Global Head of Asset Allocation Research

China’s credit growth has often been a cause for concern, especially the rising importance of shadow banking. In this update to earlier work we acknowledge the growth but see reasons for hope.

Remember China’s shadow banking problem? Five years ago, this was the next big thing that was going to sink China – or so we were told at the time. When we explored this in More pictures of China in 2018, we concluded that China’s shadow banking system had grown rapidly but only to bring it in line with that of the US and leaving it smaller than those of many European countries. If China had a shadow banking problem, then so did other countries.

Before bringing that analysis up to date, it is worth looking at the broader debt situation in China. As outlined in Global debt review 2020, China’s non-financial sector debt exceeded 250% of GDP in 2019, as did that of the US, Japan and many European countries (Germany being the honourable exception).

Though the level of China’s debt was unremarkable (relative to other large countries), the rate of change was alarming. China’s debt ratio had increased by around 80 percentage points in the most recent 10 years, the biggest increase across our universe of the world’s 25 largest economies.

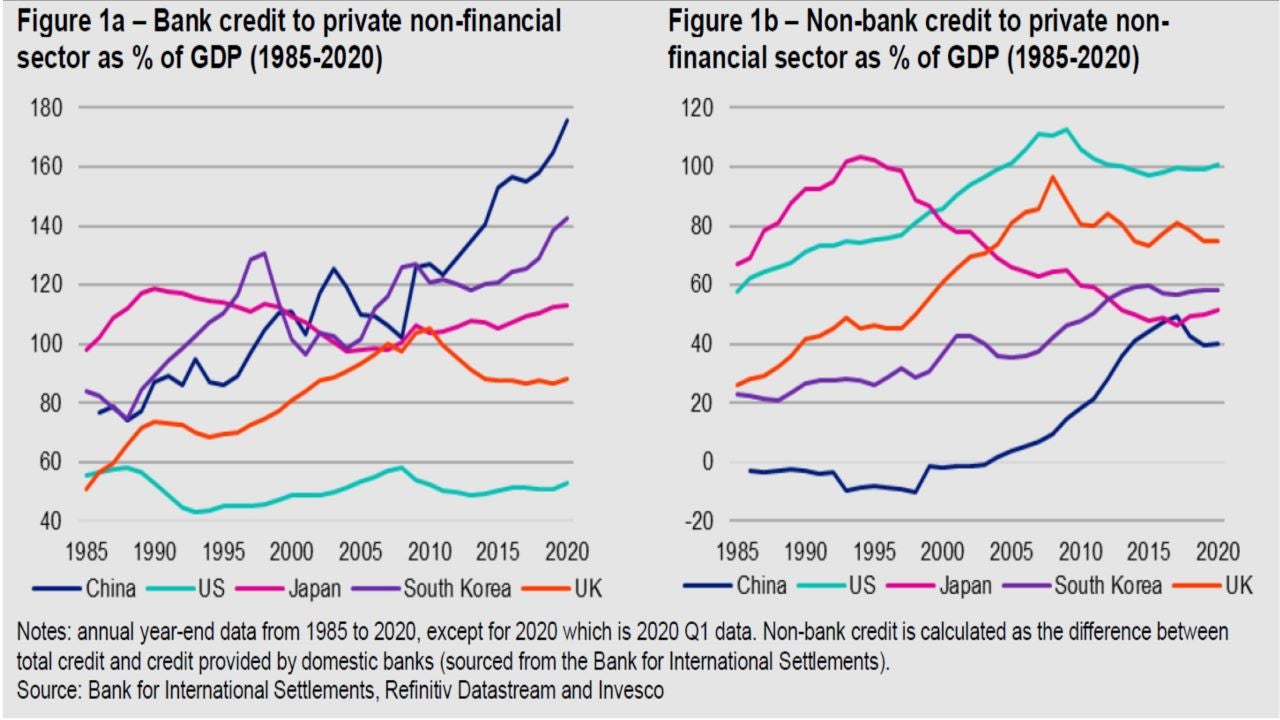

Figure 1a shows that bank lending to the private sector accounted for a large part of the accumulation of debt in China (including another jump during the first quarter of 2020). It also shows that bank financing has become a noticeably more important part of the Chinese economy than in other countries (the Eurozone looks like the UK on this score). Note the stark contrast with the US, which has tended to rely more on financial markets than other countries.

With such a large increase in China’s reliance on bank financing, there is natural concern about what will happen during an economic downturn, such as seen during the first quarter of 2020. So far, the news is reassuring with the commercial banks non-performing loans ratio rising but only to 1.94% in 2020 Q2, up from 1.86% at the end of 2019 and 1.75% a year earlier. By way of comparison, it was above 12% in early 2005 and recently bottomed at 0.90% in 2011 Q3.

Of course, bad loans and defaults tend to lag the economy, so worse may be to come but for now the news is not too bad and the economy rebounded quickly after the sharp decline in Q1. In terms of capital buffers, China reports that at the end 2020 Q2, the core tier-1 capital ratio of its commercial banks was 10.5%, down from 10.9% at the end of 2019 but above the Basel III target range of 7.0%-9.5%. When looking at the capital to assets ratio (using Tier 1, 2 & 3 capital), World Bank data suggests that in 2018 Chinese banks (9.1%) were better provisioned than those of Japan (5.4%, 2017 data), the EU (8.3%, 2017 data) and India (7.5%) but lagged those of the US (11.7%), Brazil (10.1%) and Russia (10.0%).

We would expect banks around the world to suffer heightened bad loans and defaults as a result of the Covid recession but, apart from the recent strong growth in loans, we see no reason to worry more about Chinese banks (the economy rebounded quickly and the banks appear reasonably well capitalised).

Looking at non-bank sources of credit in China, Figure 1b suggests this has also significantly increased during this century. Having started in negative territory at the end of the last century (suggesting perhaps that overseas banks were filling the gap), credit from non-bank sources had grown to nearly 50% of GDP in 2017 but had settled at around 40% of GDP in 2019 and 2020 (as of the end of Q1).

That growth in China’s non-bank credit from 2000 to 2017 looks very similar to what happened in the US and the UK from the early 1990s to the time of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and we know what happened next. Nevertheless, non-bank sources of credit are currently nowhere near as important to the Chinese economy as they were in the US and UK just prior to the GFC (and remains well below the levels seen in those countries).

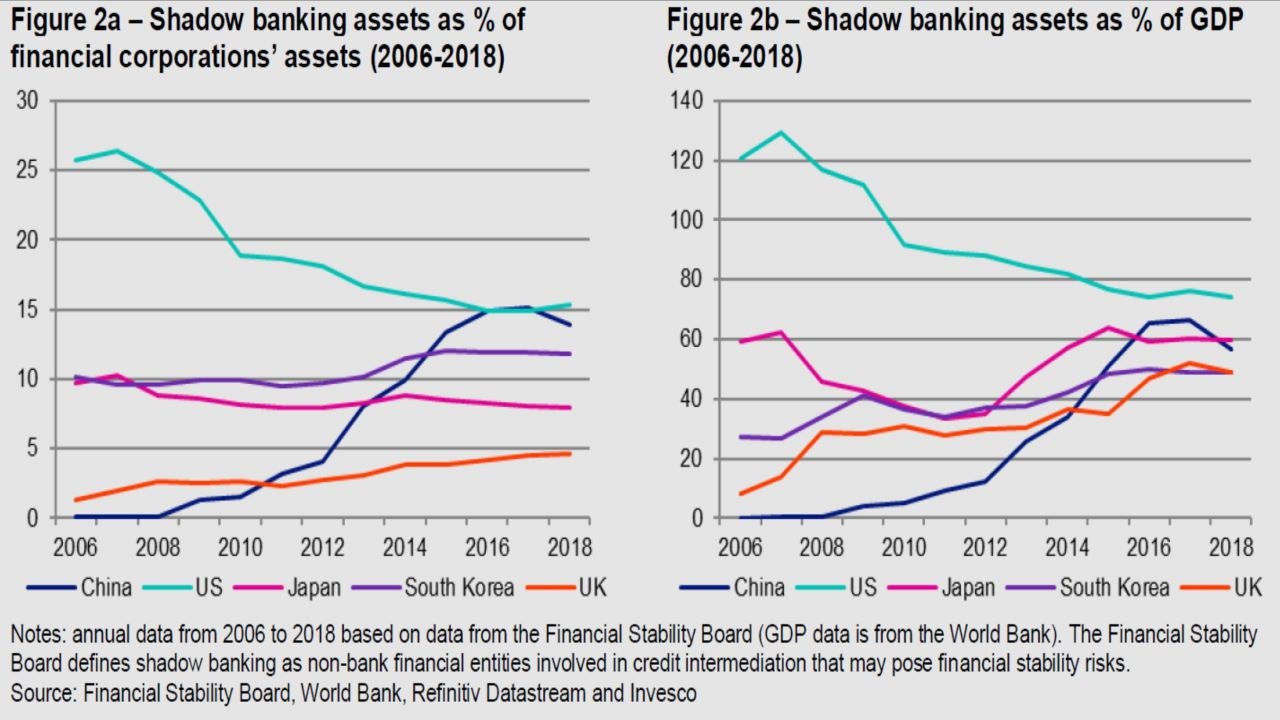

However, talking of non-bank sources of credit doesn’t really stir the emotions in the way that “shadow banking” does. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) makes a valiant effort to compile data and, though data is only available up to 2018, it allows us to compare trends across a wide range of countries (see Figures 2a and 2b).

The FSB defines shadow banking as non-bank financial entities involved in credit intermediation that may pose financial stability risks. Figure 2a shows that the assets of such institutions have grown rapidly in China over the last decade (as a proportion of the assets of all financial corporations). The trend has been the opposite in the US, with shadow banking becoming less important since the GFC. Interestingly, while shadow banking appears to have again become more important since 2016 in the US, it has become less so in China (perhaps because of policy measures to dampen such activity). Shadow banking remains more important in the US than in China.

However, Figure 2a could provide a distorted comparison across countries because central bank assets are included in the denominator. Given the use of quantitative easing in some countries, it may be fairer to compare shadow banking assets to GDP, as in Figure 2b. This again confirms that shadow banking has become more important to the Chinese economy over the last decade (as was the case in all our comparators, except the US). Nevertheless, as of 2018 it was less important in China than in the US (and Japan).

Note that it is difficult to compare the data in Figures 1b and 2b because the FSB definition of shadow banking credit is narrower than non-bank credit (and because Figure 1b concerns credit provision to the private non-financial sector, whereas Figure 2b looks at credit provided to a broader set of borrowers).

In summary, it appears that China’s financial system has evolved rapidly over the last decade and rapid change always brings the risk of errors. However, in many ways China has simply been catching up with developed world counterparts. The importance of banking finance to the Chinese economy appears greater than for our comparator panel but this could be a function of less well-developed financial markets. In any case, Chinese banks appear to be reasonably well capitalised. Likewise, shadow banking activity has increased but has recently levelled off and remains comparable to big developed economies.

Investment Risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

When investing in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in value.

Investment in certain securities listed in China can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity and/or investment performance.

当資料ご利用上のご注意

当資料は情報提供を目的として、インベスコ・アセット・マネジメント株式会社(以下、「当社」)のグループに属する運用プロフェッショナルが英文で作成したものであり、法令に基づく開示書類でも特定ファンド等の勧誘資料でもありません。内容には正確を期していますが、必ずしも完全性を当社が保証するものではありません。また、当資料は信頼できる情報に基づいて作成されたものですが、その情報の確実性あるいは完結性を表明するものではありません。当資料に記載されている内容は既に変更されている場合があり、また、予告なく変更される場合があります。当資料には将来の市場の見通し等に関する記述が含まれている場合がありますが、それらは資料作成時における作成者の見解であり、将来の動向や成果を保証するものではありません。また、当資料に示す見解は、インベスコの他の運用チームの見解と異なる場合があります。過去のパフォーマンスや動向は将来の収益や成果を保証するものではありません。当社の事前の承認なく、当資料の一部または全部を使用、複製、転用、配布等することを禁じます。

C2020-10-079

そのほかの投資関連情報はこちらをご覧ください。https://www.invesco.com/jp/ja/institutional/insights.html