China GDP target portends further monetary easing and fiscal stimulus in 2022

Ambitious GDP target is achievable, as long as inflation plays along

A key moment from Li Keqiang’s press conference closing the latest Two Sessions legislative summit was his explanation of the new economic growth target.

While the market expected guidance to be 4.5% for 2022, the government had announced instead a notably ambitious 5.5% growth target, ahead of my own expectation of 5%.

While light on details, Mr. Li indicated that policy to drive growth would include some tax reductions and employment support. Monetary policy will also be central to this effort.

We have already seen substantial monetary policy divergence between China and the US since the start of the pandemic, but we can expect this to go into overdrive over the rest of the year as Beijing policymakers shower the economy with stimulus to meet this high bar, all while the Fed tightens monetary policy to tackle high inflation.

It has been two long years since central banks across the world, led by the Fed, enacted extraordinary monetary policy actions to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. Back then, a nascent rate rising cycle at the Fed came to a screeching halt as the virus spread, with interest rates slashed and the return of aggressive quantitative easing, coupled with fiscal policies that injected trillions of dollars directly into the economy.

These programs were effective in putting a floor under the financial damage COVID would ultimately cause, but this success was achieved at the cost of inflation, which classical economists would argue was inevitable given the sheer scale of monetary policy expansion.

Contrast this with what the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) did in 2020. Before COVID, monetary policy was focused on broad de-leveraging and macroprudential reforms (i.e., the three red lines to limit real estate leverage). No additional asset purchase programs were launched in 2020 even as the pandemic exploded; the PBoC essentially tinkered with policy to create more favorable conditions for commercial bank lending and liquidity.

Despite COVID hitting domestic consumption throughout 2020, Chinese monetary policy didn’t make a clear shift until December, at which point the PBoC cut interest rates on both short-term reverse repos and the Medium-Term Lending Facility (MLF), while also cutting the Reserve Requirement Ratio for commercial banks.

This enabled money and credit growth to expand, but considerably less so than in the US. In 2020, China’s M2 money growth clocked in at 10.1% year-over-year, versus 24.8% in the US. The divergence narrowed in 2021, with China money growth at 9% against 12.9% in the US.1

Source: People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and Federal Reserve. Data as of Jan 2022.

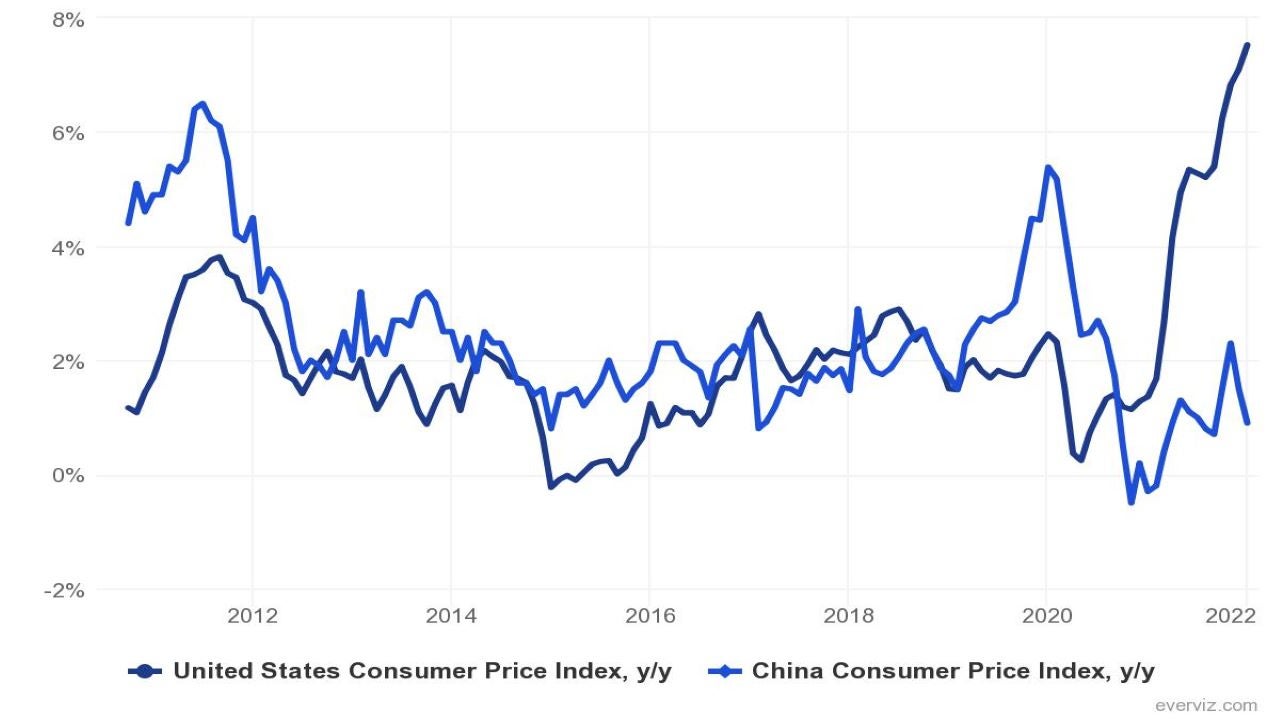

This also resulted in much lower inflation – whereas the January 2022 US CPI print showed 7.5% year-on-year inflation, in China the same figure was only 0.9%.2

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Data as of Jan 2022.

With the Fed now accelerating its tapering of asset purchases and starting a new rate rising cycle in March, the contrast with China couldn’t be any starker.

The PBoC’s current approach simply isn’t sufficient to reach their 2022 GDP target, as the challenges facing the Chinese economy are coming into clearer focus. The relentless outbreak of the Omicron variant in Hong Kong is likely to push Chinese authorities to double down on their Zero-COVID policy, especially as the proportion of unvaccinated seniors remains worryingly-high.

Despite the current omicron outbreak on the mainland, I believe the government will be able to tackle this wave of infections, and the Zero-COVID policy will remain in place until a homegrown mRNA vaccine and effective treatments are broadly available. This is likely to happen sometime this year, but will prevent domestic consumption rebounding to pre-COVID levels until it happens.

The massive property sector also remains under pressure, but similarly to Zero-COVID, the Three Red Lines policy isn’t likely to go anywhere for the foreseeable future. Even though the government has made clear it does not see real estate speculation as healthy for the overall economy, policymakers could nonetheless relax property restrictions as we’ve recently seen some stabilizing of home prices, which could indicate that the credit cycle has already bottomed out.

This year’s GDP target will also need to be supported by robust infrastructure stimulus at the local level. Local governments have historically been a large driver of borrowing for major infrastructure projects – there are some indicators this is picking up, for example in renewed spending on metro systems.

Regardless, a supportive monetary backdrop isn’t enough to give the economy a boost –businesses will need to respond with increased credit appetite to fund real commercial activities. So far there have been mixed signals on this – bank lending actually slowed slightly in January 2022 versus September 2021, although Q4 2021 credit data demand showed a slight improvement.3

As always, sustainable growth comes from economically productive investments. This will continue to flow to high-end manufacturing, technology, alternative energies, services, and a strong domestic consumption base.

The question is how long the Chinese stimulus can go on without a concerning rise in inflation? The eruption of war between Russia and Ukraine has thrown a wrench in this calculation with a rapid runup in commodity prices and a major re-pricing of risk.

Similar to the challenges faced by its peer institution, the Fed, we believe the PBoC may need to navigate massive economic forces that conspire to complicate their well-laid plans. Given that China has almost always met or exceeded its GDP growth guidance, history is on their side.

A version of this article appeared in South China Morning Post on 16 March, 2022.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

When investing in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in value.

Investment in certain securities listed in China can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity and/or investment performance.

Footnotes

-

1

People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and Federal Reserve. Data as of Dec 2021.

-

2

China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Data as of Jan 2022.

-

3

People’s Bank of China (PBoC). Data as of Dec 2021.

当資料ご利用上のご注意

当資料は情報提供を目的として、インベスコ・アセット・マネジメント株式会社(以下、「当社」)のグループに属する運用プロフェッショナルが英文で作成したものであり、法令に基づく開示書類でも金融商品取引契約の締結の勧誘資料でもありません。内容には正確を期していますが、必ずしも完全性を当社が保証するものではありません。また、当資料は信頼できる情報に基づいて作成されたものですが、その情報の確実性あるいは完結性を表明するものではありません。当資料に記載されている内容は既に変更されている場合があり、また、予告なく変更される場合があります。当資料には将来の市場の見通し等に関する記述が含まれている場合がありますが、それらは資料作成時における作成者の見解であり、将来の動向や成果を保証するものではありません。また、当資料に示す見解は、インベスコの他の運用チームの見解と異なる場合があります。過去のパフォーマンスや動向は将来の収益や成果を保証するものではありません。当社の事前の承認なく、当資料の一部または全部を使用、複製、転用、配布等することを禁じます。

IM2022-012

そのほかの投資関連情報はこちらをご覧ください。https://www.invesco.com/jp/ja/institutional/insights.html