Uncommon truths: Is China over-investing?

Posted by Paul Jackson, Global Head of Asset Allocation Research

China is often accused of over-investing and its capital productivity has fallen. However, marginal efficiency of capital is positive and return on equity is in the middle of the developed comparator range.

We recently wrote that China’s economy is in reasonable external balance but noted that investment is extremely high when compared to other countries. China’s investment spending has represented 40%-50% of GDP throughout most of this century but has been easily financed because savings have been even higher (see China in the balance).

External balance is one thing but what about the effect of high levels of investment on the domestic economy? Just as too little investment can be a bad thing, too much can render projects unprofitable and create economic inefficiencies and losses. China has often been accused of building roads to nowhere or even worse to newly constructed ghost towns If this were true it could boost employment and income in the short term but would imply a loss of efficiency over the long term as those projects fail to give economic returns.

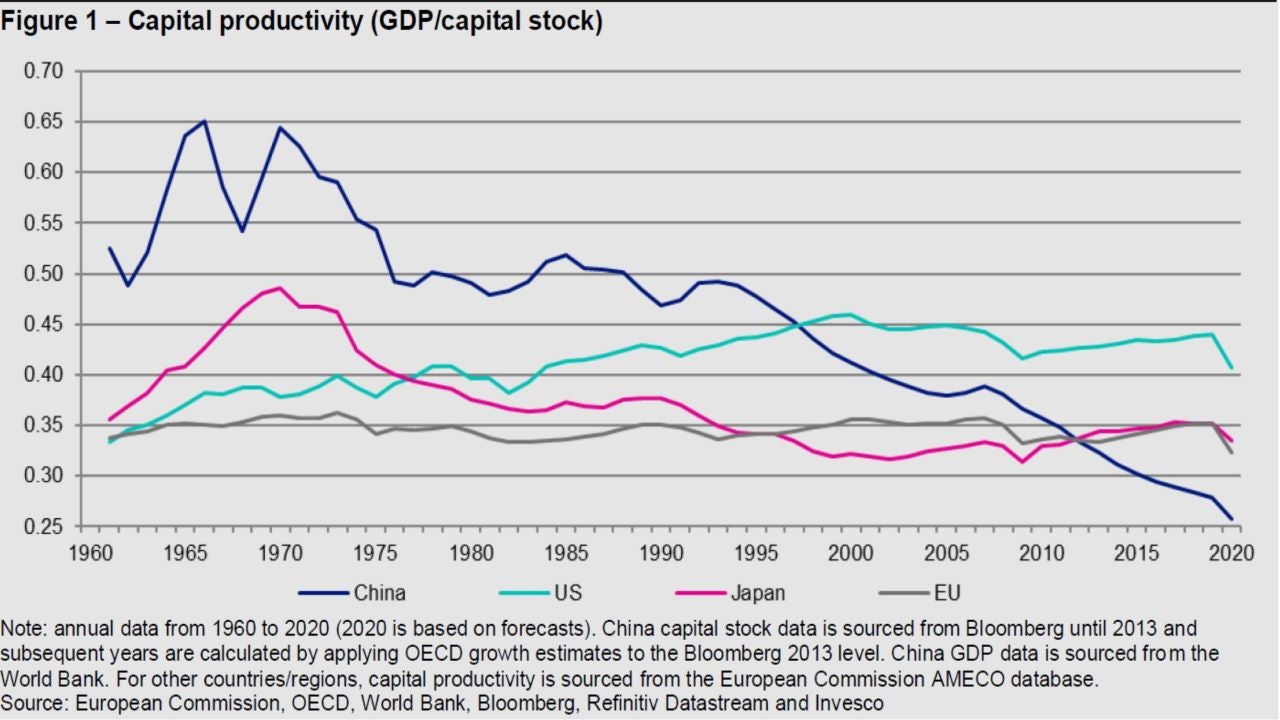

One way to judge the efficiency of investment is to look at capital productivity (though finding the data for China is a challenge). Figure 1 shows the simplest of measures: GDP divided by the capital stock. When this measure of average capital productivity is on the rise, it suggests that recent investment has given more GDP returns than was the case in earlier periods (not surprisingly, capital productivity declines during recessions, as predicted for 2020). For example, US capital productivity improved throughout the 1960-2000 period but has since levelled off and declined slightly.

Japan has followed the opposite path, with high post-war capital productivity giving way to decline from 1970 to 2000, perhaps due to over-investment in the 1970s and 1980s. However, since the start of this century, capital productivity in Japan has improved again and is now back in line with that of the European Union (which itself has been relatively stable since 1960).

China appears to have gone through a dramatic transition. During the Mao era, we would guess the country suffered from under-investment (see the high capital productivity in the 1960s and 1970s), making it easy to invest profitably. Though productivity stabilised at a lower level in the post-Mao era (he died in 1976), it remained well above that of the comparator countries until the end of the last century.

It was during Deng era that investment spending became more important, approaching 40% of GDP in the mid-to-late 1980s and finally exceeding that level for a few years in the early 1990s. The cumulative effect of all this investment spending was to lower capital productivity, which started on a new downtrend in the mid-1990s, a downtrend that is ongoing.

That doesn’t look good. Not only is China extracting less benefit from its capital stock than at any time since at least 1960, it also appears to be getting less benefit than developed country counterparts (with the US doing better than Japan and the EU).

However, the fact that China is suffering diminishing economic returns from its investment does not mean the investment should not have occurred, nor that it should not continue. The important question is whether China is deriving any benefit from its investment spending. One way to judge that is to look at the marginal efficiency of capital (the return on the latest yuan of investment spending).

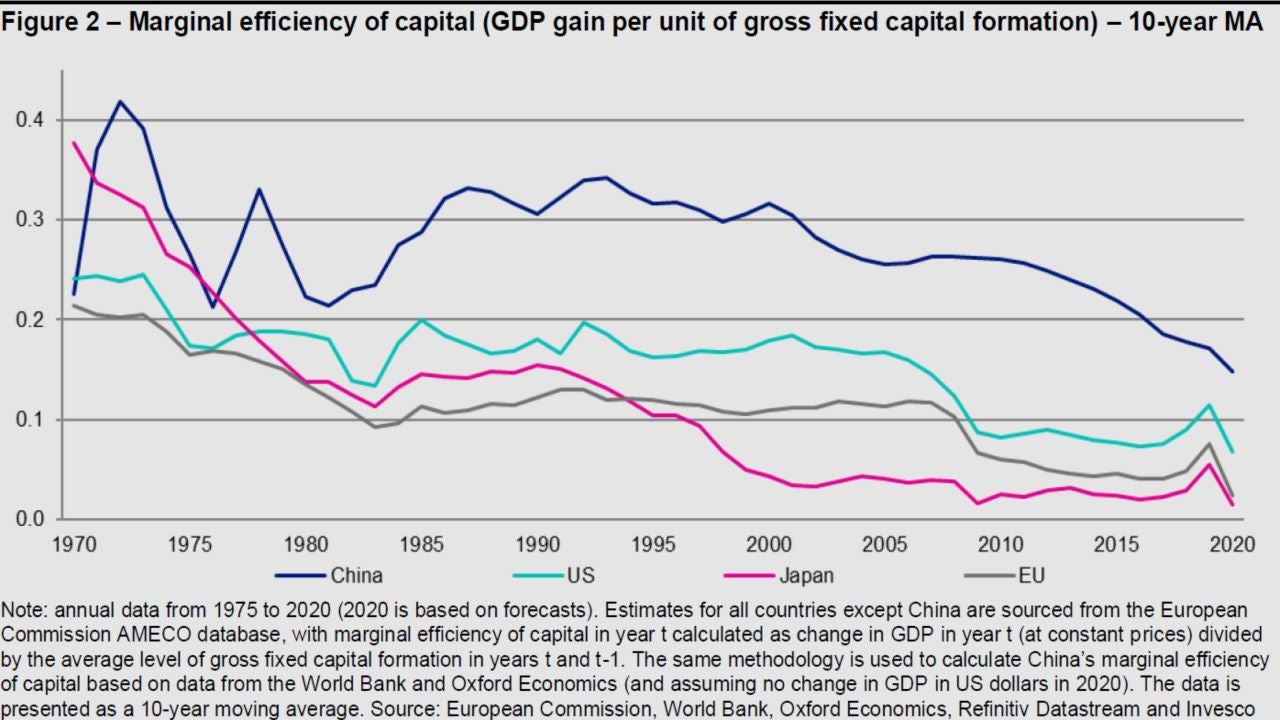

Figure 2 shows one such measure, as calculated by the European Commission (EC), along with our own calculations for China. Put simply, it shows the GDP gain for each unit of gross fixed capital formation, calculated as the change in GDP in year t divided by the average level of gross fixed capital formation in years t and t-1. It is naturally cyclical, with sharp declines during recessions, as is forecast for 2020, which is why we show a 10-year moving average (which we think reveals more than it hides). Sadly, the different methods of calculation render it hard to make comparisons between average productivity (Figure 1) and marginal productivity (Figure 2).

Though China’s marginal efficiency of capital has recently been less than half what it was in the 1980s and 1990s (and is trending down), it has remained positive and above that of comparator countries (our calculations suggest it will be close to zero in 2020, while EC calculations suggest it will fall into negative territory for our comparators).

This suggests that, while China’s use of capital is less efficient than it used to be, there is still scope to reap economic benefits from further investment (by movingrural populations into urban areas and making them more productive, for example). If our calculations are correct, China is better placed than our comparators to benefit from further investment spending, though the gap has closed.

All the above looks at investment spending from a total economy perspective, including the public sector. From an investor’s perspective, return on equity (ROE) is another way to look at it (we use a five-year moving average of ROE derived from Datastream indices). On this basis, US ROE has been between 12% and 16% for most of the last 30 years and has consistently been at the top of the comparator country range. China’s ROE approached 20% in the early 1990s but averaged only around 10% in the late 1990s/early 2000s and has since averaged around 12% (and matched that of the US in the aftermath of the GFC). EU and Japanese ROE averaged 6%-10% over the last decade, with that of the EU falling from US levels in the early 2000s (when banks were profitable) and that of Japan gradually rising from the 4% average seen in the early 1990s. We expect ROE to be lower in 2020 in all countries.

Our conclusion is that China’s investment is less productive than it was but is still adding economic value. ROE may be lower than in the US but is higher than in the EU and Japan, which suggests to us that valuation ratios should be lower in China than in the US (lower PE for the same PBV, say) but higher than in other developed markets.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 28 August 2020

Investment Risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

当資料ご利用上のご注意

当資料は情報提供を目的として、インベスコ・アセット・マネジメント株式会社(以下、「当社」)のグループに属する運用プロフェッショナルが英文で作成したものであり、法令に基づく開示書類でも特定ファンド等の勧誘資料でもありません。内容には正確を期していますが、必ずしも完全性を当社が保証するものではありません。また、当資料は信頼できる情報に基づいて作成されたものですが、その情報の確実性あるいは完結性を表明するものではありません。当資料に記載されている内容は既に変更されている場合があり、また、予告なく変更される場合があります。当資料には将来の市場の見通し等に関する記述が含まれている場合がありますが、それらは資料作成時における作成者の見解であり、将来の動向や成果を保証するものではありません。また、当資料に示す見解は、インベスコの他の運用チームの見解と異なる場合があります。過去のパフォーマンスや動向は将来の収益や成果を保証するものではありません。当社の事前の承認なく、当資料の一部または全部を使用、複製、転用、配布等することを禁じます。

C2020-10-080

そのほかの投資関連情報はこちらをご覧ください。https://www.invesco.com/jp/ja/institutional/insights.html