Asset allocation Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs) | 2025

Invesco Investment Solutions erstellt Kapitalmarktprognosen (CMAs), die langfristige Einschätzungen zum Verhalten der wichtigsten Anlageklassen weltweit liefern.

![Central banks [are] not the only game in town](/content/dam/invesco/uk/en/insights/il2905-central-banks-are-not-the-only-game-in-town.jpg)

Mario Draghi’s ‘parting gift’ of more QE, another rate cut, deposit tiering, and a more favourable TLTRO scheme was coupled with a strong message to governments across Europe: “It would be nice if the economies at large did not have to rely on central banks yet again in order to resist the next shock.”

The monetary response to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has been unprecedented. To us it is very significant when the same people responsible for implementing monetary policy are now calling for more fiscal stimulus. Take a recent speech by ECB President Draghi in Sintra, Portugal:

Mario Draghi, ECB PresidentIt would be nice if the economies at large did not have to rely on central banks yet again in order to resist the next shock.

More recently Christine Lagarde, the ECB president-elect, urged governments whom: "have the capacity to use the fiscal space available to them (to start investing in their infrastructure)."

As part of the same speech she urged the stronger Eurozone nations to spend more during downturns as central banks cannot do it all alone - “I’m not a fairy.”

Judging by how conservatively markets are positioned, barring the most recent week or two, fiscal spending is not something that is being taken very seriously today. Maybe this is unsurprising as markets have only ever experienced a very restrictive fiscal stance since the GFC. With Germany – central to European policy - doggedly sticking to fiscal discipline, it has been much easier to assume a continuation of what has happened in the last decade than anticipate a change in direction.

To some in financial markets, fiscal policy will only be used if the economic situation is dire, implying equities would have to be much lower before fiscal taps are turned on. Our view is somewhat different. Not only is there already evidence of policy shift – several governments are already introducing more expansionary fiscal measures – but good reasons to believe fiscal policy can become a good deal more accommodative for several years.

Should such a policy shift materialise the implications for European equities, and in particular the type of stocks one might favour within the market, would be very significant. Many people still fear Europe could end up in a vicious circle of stagnant growth and deflation – conditions Japan have grappled with for a long time. This anxiety is not helped by underlying inflation stubbornly sticking to around 1% (well below the ECB target), despite huge monetary help. A more proactive, long-term fiscal policy would go a long way to addressing some of the concerns over growth. It would also put upward pressure on bond yields thereby reducing some of the attractiveness of bond-like equities.

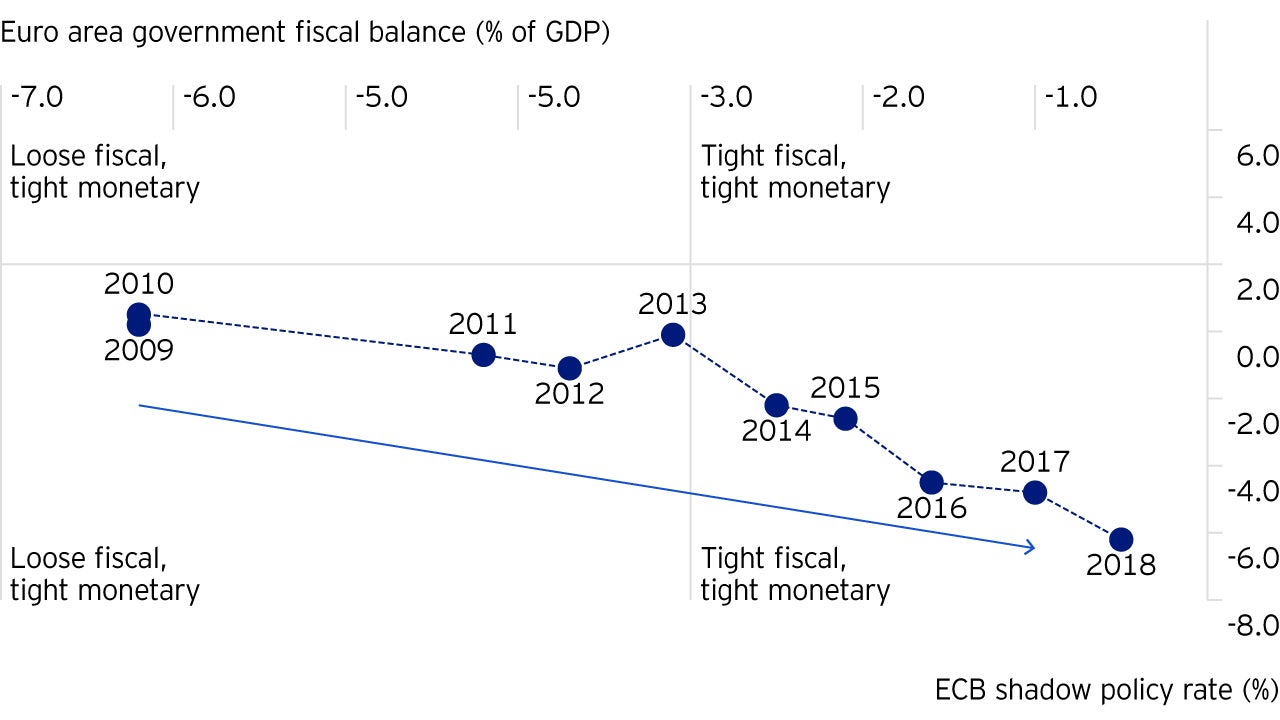

Since the GFC there has been an unusual divergence between monetary and fiscal policy. To combat the systemic financial risks huge monetary stimulus was provided. Fiscal policy - in practice austerity - focused on repairing government finances – especially those countries in the periphery. The chart below highlights this. In effect, using the Wu and Xia methodology in which they construct a shadow European monetary policy rate, the effective interest rate is -7% today. This compares to around zero in 2009. In contrast fiscal policy has gone completely the other way – it has tightened by 5.5%, from -6% to -0.5%. It is worth taking note that the fiscal balance is not expected to tighten this year, the first time since 2009.

The ECB’s reaction to the existential crisis in 2012 and subsequent measures were successful in supporting Europe through a very challenging period. Quantitative Easing drove asset prices higher creating capital gains on banks’ bond portfolios. These gains were used to absorb losses coming from the loan book. It also gave banks time to repair their equity. Meanwhile low interest rates stemmed the flow of new non-performing loans (NPLs). In many ways quantitative easing was incredibly effective.

However, it has been less successful in getting inflation back to the ECB target. Moreover, loose monetary policy has also created unintended consequences (something we have discussed in earlier pieces: Hiding in plain sight, The haves and have-nots). Asset inflation has favoured the asset rich as opposed to those exposed to the real economy i.e. much of the electorate, driving a bigger gap between the rich and the poor.

This headwind, as well as a very restrictive fiscal policy, is causing rising resentment across Europe. The Gilets Jaunes’ protests in France and acrimonious budget discussions between Italy and the European Commission (EC) are symptoms of the building frustrations. The threat to the harmony of the European Union is clear.

We are now seeing several governments introduce, or set to introduce, more accommodative measures:

For governments to remain in power, or indeed be elected in the first place, they are increasingly needing to adopt a more pro-fiscal stance. Our belief is that a government manifesto based on austerity is going to struggle to win over the voting population. It would also be wrong to dismiss the importance of the environment as an issue today. Taking this seriously would require a significant investment from government which is likely to prove popular with the electorate.

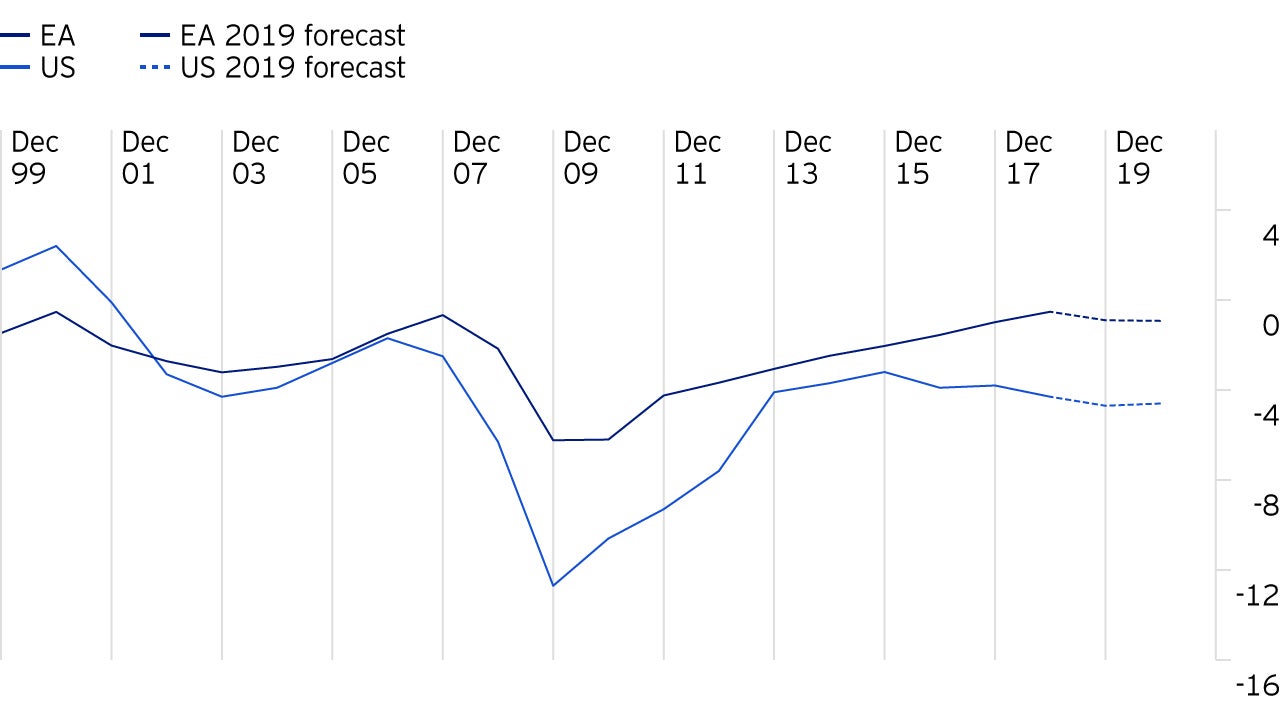

There is significant financial headroom available at the European level, especially in comparison to other countries like the US.

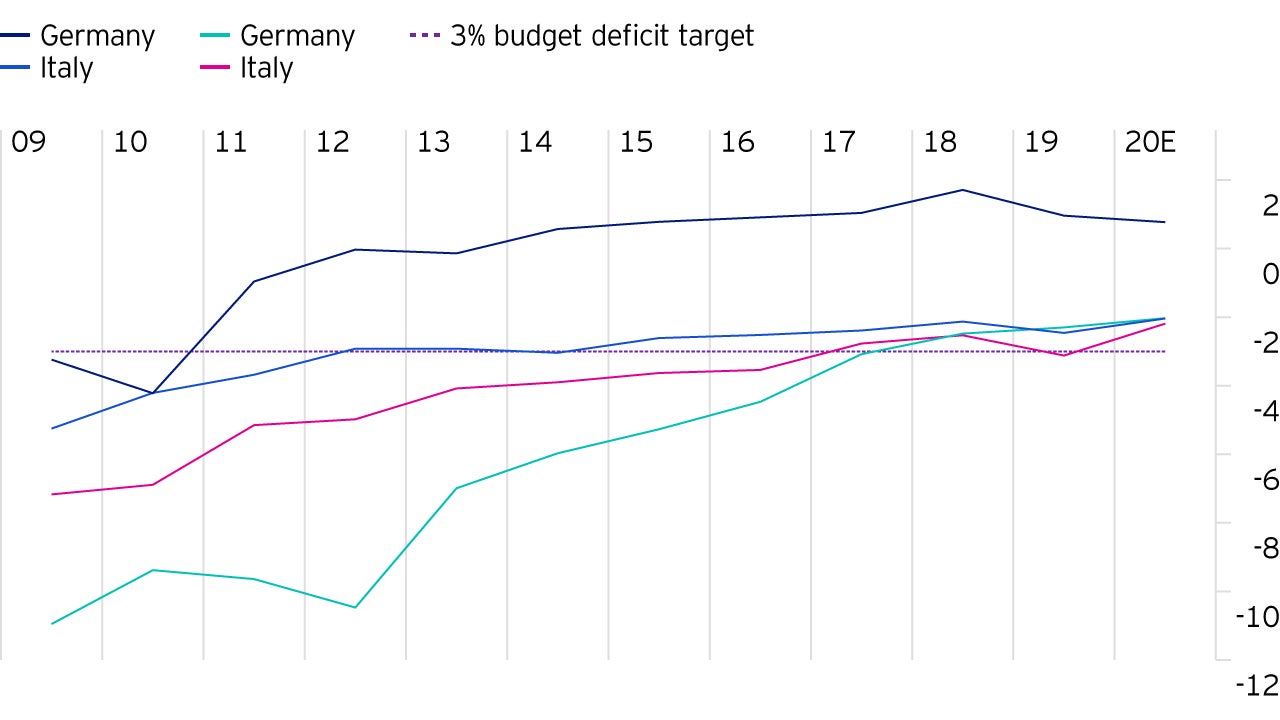

However, this fiscal headroom is not uniform across Europe. Simplistically - by looking at budget deficits in isolation - the major European countries are within the 3% level required by the EC. Of course, the EC looks at this measure in combination with debt to GDP. However, well targeted fiscal plans would provide an uplift to GDP too.

Assuming the ‘Big 4’ European nations use most of the available headroom, would these measures be enough for inflation to move towards the ECB target of around 2%? We think it would be a significant step in the right direction. Of course, further measures are likely to be needed – possibilities range from less onerous stability and growth pact rules to help from EU Institutions.

As mentioned earlier, Germany is the key blockage to a more expansive fiscal policy at the Eurozone level – they have doggedly stuck to a policy of profound fiscal prudence since the GFC and show little sign of change. Even so - due to a confluence of issues – it is difficult to ignore the rising pressure on Germany to re-assess its fiscal stance.

The importance of the autos sector to the wider German economy - both the manufacturing of and the companies involved in the supply chain - cannot be underestimated. It is not just cars either. Germany has benefitted from exporting to China, something which is unlikely to remain a key driver of growth moving forward.

How will the industry deal with the threat from the transition to Electric Vehicles? Should the government invest more into Electric Vehicles? Does Germany have the right infrastructure to manage that transition? Would it make sense to try to support and grow other industries? The state of the infrastructure is not what it once was – this acts as a brake on both productivity and growth. In addition, Germany is undergoing a major energy transition with most of its nuclear fleet due to be switched off by the end of 2022. After a period of very strong economic growth – even when many other countries were struggling – the outlook does not look as assured as it once did. Demographics are another big obstacle. We think it is critical for the government to increase investment.

Far from being politically stable, there are new forces disrupting the status quo in Germany. It seems difficult to see how the Green Party does not have an important role to play in the future. Their successful European Parliamentary campaign followed by the strong showing in recent polls leaves them well placed. We would expect them to prioritise spending on the environment - an area 70% of the German population believe the government is not doing enough about. At the very least the existing coalition – SDP/CDU/CSU – would need to acknowledge the importance of this issue and respond accordingly. Some of the key fiscal hawks, Angela Merkel for example, are not as influential as they once were. Many of the key proponents of this policy are approaching the twilight of their careers too.

Would this scale of investment breach the “black zero rule” (i.e. running a balanced budget)? Whilst it will not be easy to change this rule, as it is part of constitutional law, the business and political changes outlined above could provide the momentum needed to adapt/amend the existing rules. We already appear to be seeing early signs of change based on the steady stream of headlines and quotes in recent weeks. We provide some examples below:

"Germany considers 'shadow budget' to circumvent national debt rules." - Reuters

"It is absolutely crucial — if an economic crisis actually breaks out in Germany and Europe — that thanks to our sound finances we will be able to counter it with many, many billions." - Olaf Scholz, German Finance Minister

"The debt brake is absurd and is harming Germany." - Marcel Fratzscher, Head of The German Institute for Economic Research

"If we do not invest now, we will not only burden the present generation, but also leave even higher investment needs for the future generations." - Michael Huether, Director of The German Economic Institute

It is all too easy to assume fiscal policy in Germany is only ever going to be restrictive, however we take the view there are compelling reasons for change. If this were to happen, for example much greater investment in industry or the environment, it could facilitate change at the European level too. Significantly, the change in personnel at some of the key European institutions could support this change. There is a good balance of nationalities in some of the key positions, ranging from the appointment of Christine Lagarde from France as ECB President to Paolo Gentiloni from Italy as the new EU commission economics minister. Following Gentiloni’s appointment, the former Italian prime minister commented:

"I will work, above all, to contribute to boosting growth and social and environmental sustainability of that growth." - Paolo Gentiloni, EU commission economics minister

It is not just the individual governments that could do more. A Eurozone budget could help facilitate a more pro-fiscal policy. Institutions like the European Investment Bank have significant financial resources for investment. Many doubt any progress will be made, but completely ignoring the possibility poses its own risk. Following the European Parliamentary elections, the influence of ‘Green’ parties is a great deal more significant than it was. By joining forces, this group could drive the need to invest in climate action and force it to become a much higher priority for European institutions. These parties tend to be staunchly pro-European too.

The appointment of Ursula Von der Leyen to the Presidency of the European Commission is positive too - an extract below from her opening statement in the European Parliamentary Plenary Session – 16 July 2019.

"I will propose a Sustainable Europe Investment Plan and turn parts of the European Investment Bank into a Climate Bank. This will unlock €1 trillion of investment over the next decade." - Ursula Von der Leyen, President of the European Commission

Many have given up on a European budget ever being created. Yes, progress has been painfully slow, but things are finally starting to happen. In June 2019 the Eurogroup, made up of the Finance Ministers of all the EU nations, agreed on a common Eurozone budget in principle. It is lacking in scale and funding details need to be worked out, but it is still an important step in the right direction.

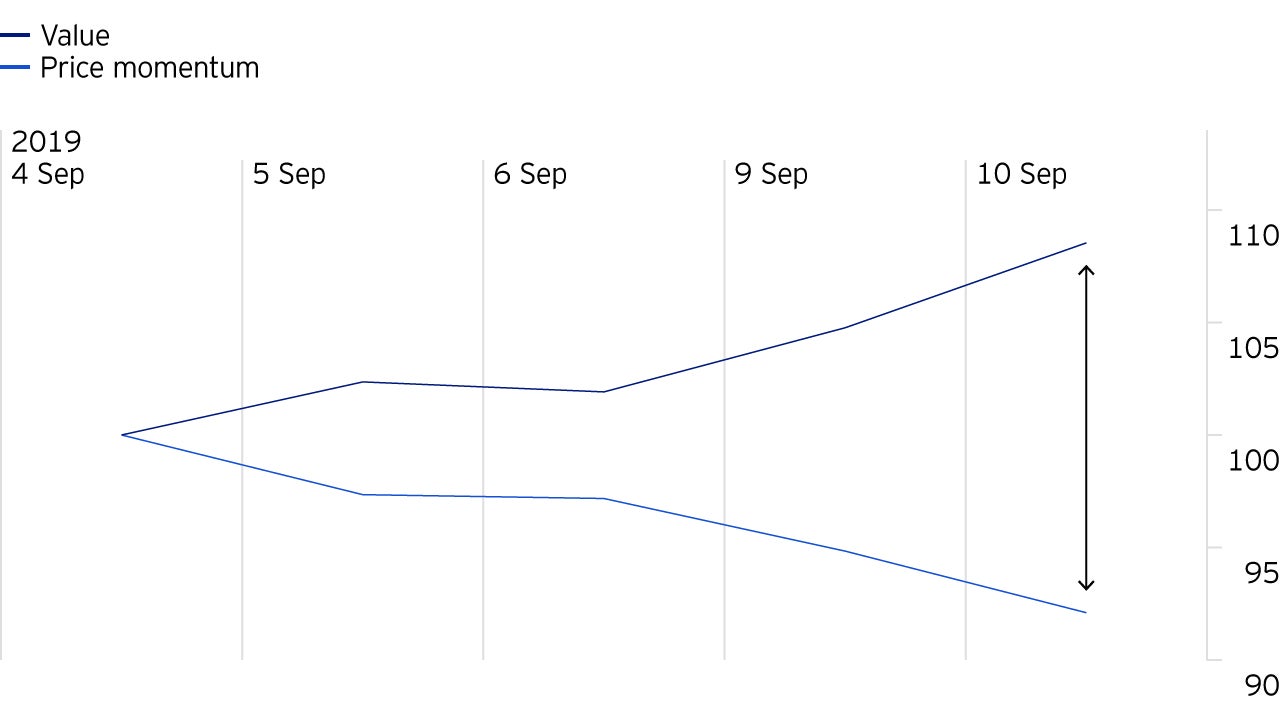

For this piece we have not gone into specific details of any potential stimulus – how big it could be, should it be through tax cuts or investment – as it is too early to know at this stage. More important to us – given the extreme nature of positioning – is how sensitive markets are to changes at the margin. This has been evidenced over the last week with a collapse in the ‘Momentum’ factor, which has dominated market performance this year, and a commensurate aggressive rotation towards the ‘Value’ factor.

Since 4 September and at the time of writing, ‘Value’ has outperformed ‘Momentum’ by 16% (see chart below). It is difficult to point to a significant piece of news that has driven the moves – instead the trigger appears to have been some slightly less bearish sentiment on a combination of China trade, economic data and German fiscal policy.

With this in mind, any change in fiscal policy could have a significant impact on share prices. No longer could one automatically assume Europe is headed for deflation – a la Japan. If anything, this could trigger an uplift in both real and nominal GDP. Debt markets would also potentially be impacted; is such a scenario consistent with a negative nominal 10-year German bund yield?

As well as arguing for a lower equity risk premium for the asset class, many of the companies we own would directly benefit from a stronger domestic European economy – ranging from banks to staffing and media agencies. Many of these are on very attractive valuations – a sign much of the market does not believe any change to the outlook is likely.

As regular readers of our work will know, we try to be open minded: if we can find a good quality franchise with improving fundamentals, an undervalued return profile and interesting capital allocation policy, we will happily consider owning it – whatever the sector. For much of this year markets have prioritised low risk/high quality above all else. Days like we have experienced this week should act as a reminder to markets that ignoring valuation can be a dangerous game. Today that means being exposed to ‘Value’ – where, in our opinion, the best valuation opportunities lie.

Invesco Investment Solutions erstellt Kapitalmarktprognosen (CMAs), die langfristige Einschätzungen zum Verhalten der wichtigsten Anlageklassen weltweit liefern.

Auf dem Weg zur weltweiten Klimaneutralität und Dekarbonisierung der Energiewirtschaft könnten europäische Versorgerwerte den Markt hinter sich lassen. Erfahren Sie mehr.

Invesco Investment Solutions entwickelt Kapitalmarktprognosen, die langfristige Einschätzungen zum Verhalten der wichtigsten Anlageklassen weltweit liefern. Das Team widmet sich der Entwicklung ergebnisorientierter Multi Asset Portfolios, die sich an den spezifischen Zielen der Investoren ausrichten.