.jpg)

Extending life

Human ingenuity is clawing back territory from the Grim Reaper. That comes with a new set of challenges for our species.

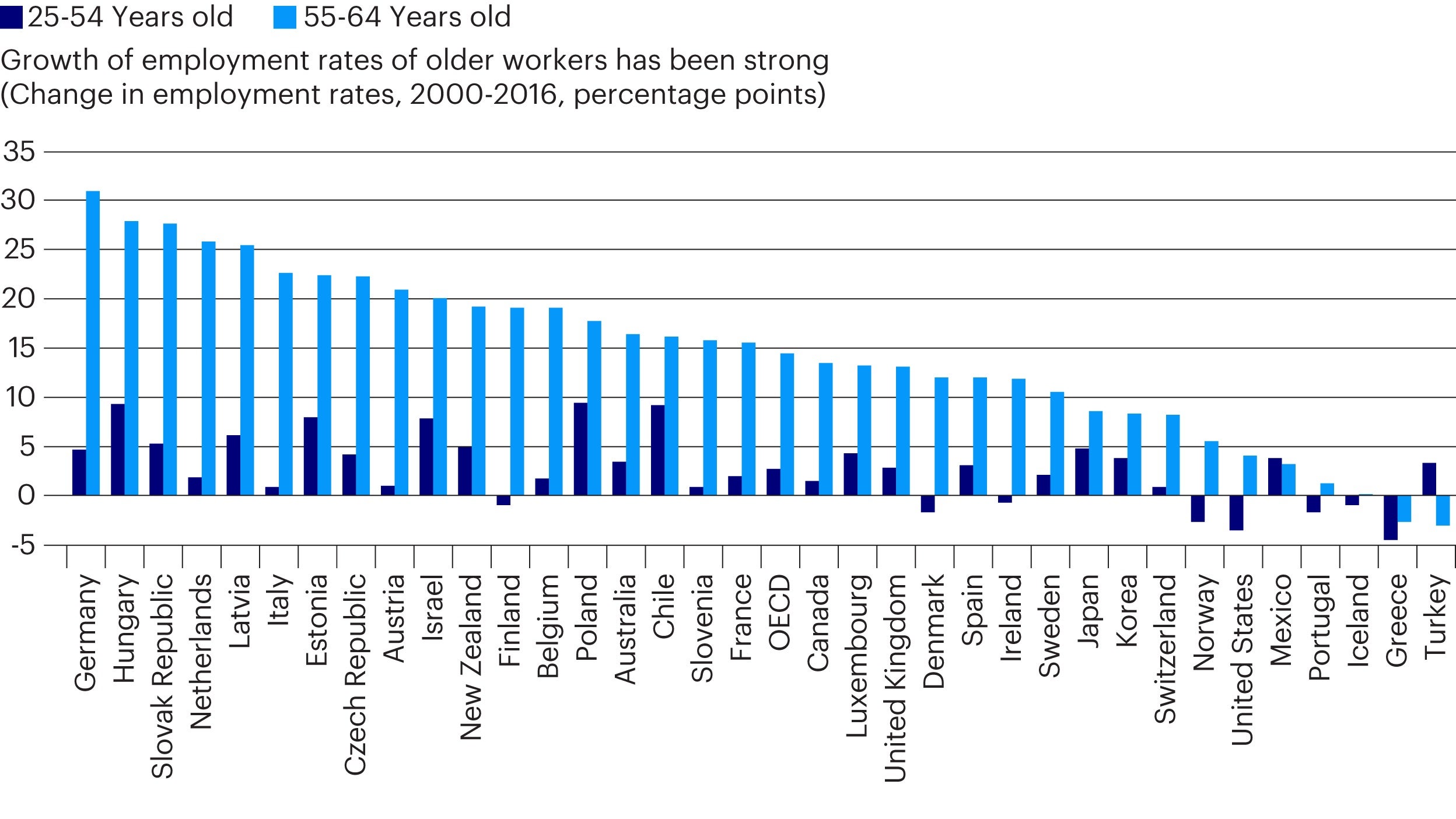

As our lifespans lengthen, it’s commonly argued that young workers will see an increasing share of their incomes dedicated to supporting others, while also needing to save more to provide for their own longer old age. Retirement ages are rising in many developed economies, but there’s little appetite for working well into your 70s. Working longer, spending less, saving more, all with a reduced security net—it isn’t an attractive proposition. Is there an alternative?

The starting point is reframing the concepts of work and retirement, argues Andrew Scott, professor of economics at London Business School. He says that stretching out education, work and retirement as monolithic blocks over longer time periods won’t work, "because if you’re living to 100 that’s a 60-year career, and that sounds pretty miserable". Moving away from an expected retirement age would address this by allowing for individual differences and facilitating later working lives that are through choice, rather than necessity.

That’s already changing how the relationship of working to non-working lives is structured, as we begin to see a much greater diversity in when people retire. Within the EU, although retirement ages are trending upwards, many continue to work part-time after retirement in self-employed roles.1 In addition, there’s a trend in developed countries to introduce flexible retirement ages.2

Giving people more opportunity to change careers, to work more flexibly—something covid-19 has thrown into relief—and to switch between entrepreneurialism, community work and education is both appealing and, arguably, necessary. "If you don’t," says Mr Scott, "it’s going to be a terrible allocation of time, as there’s not much you can learn at 20 that’s still relevant when you’re 70 or 80."

Jim Pugh, Co-founder, Universal Income ProjectWhen we say living longer, do we mean simply extending old age? Or do we mean longer productive periods?

This is echoed by Jim Pugh, co-founder of the Universal Income Project, who asks, "When we say living longer, do we mean simply extending old age? Or do we mean longer productive periods?" If people are contributing to society for longer, we shift the idea of an older population from being a burden to being a benefit.

One solution that has been floated—and trialled in various countries from Finland to Kenya—is universal basic income (UBI). This is a government payment made to all citizens, guaranteeing a minimum level of subsistence. Proponents of UBI see it as creating an infrastructure so that people can be more productive and fully participating in society, which is exactly the sort of situation you would want if you’re talking about large-scale changes and people’s lifespans.

UBI, however, doesn’t come cheap. For the US, Mr Pugh estimates total annual transfers would be about $3-4trn, giving every adult $1,000 each month, and perhaps every child $250, "which is really subsistence-level," he says. This could potentially be sustained with a transfer repayment tax, where if you are earning money you pay a percentage of your basic income back, repaying the full amount at four times the poverty level. That could drop the net cost by a factor of three or four, says Mr Pugh. Income tax rates in line with the pre-Reagan era in the US is one possible method of covering the remaining cost of UBI alongside the transfer repayment tax.

While Ros Altmann, pensions expert and member of the UK’s House of Lords, concedes that UBI has great appeal as a ‘leveller’, she asks, "who would set the level, and wouldn’t politicians be tempted to tweak it for certain groups?" This could, she says, recreate the same problems as found in the current welfare system. "Some people will spend all their income and society will not be able to leave them penniless. Others will have greater needs, and the list of exceptions would keep growing."

The potential of UBI is still an open question. Finland is the only country that has completed a nationwide randomised control trial of a basic-income programme, with consultant McKinsey summarising the evidence for or against UBI as slim.3

Another way of looking at this, more optimistic than Baroness Altmann’s free-rider concerns, is to see UBI, somewhat like AI, as releasing human potential—giving people the time to develop their own creativity, rather than being another cog in the machine.

Although the sums involved in UBI are eye-watering, Mr Pugh says that how societies are already responding to covid-19 could catalyse change. "Anytime you have a crisis moment like this, it makes people rethink their ideas." He points to the possibility of the ongoing technological transformation providing the basis for this. "We are figuring out new, more efficient ways of doing things," he says. "Much of the technological innovation today offers greater potential to be able to accomplish more with less, so even if you had a lower percentage of working hours across someone’s lifetime, people could be doing quite well."

That, however, as someone once said, isn’t how we do things round here. The world is geared for growth—if GDP doesn’t increase from one year to the next, it makes headlines; if profits dip, investors bail. Implicitly, then, addressing these needs is a challenge to our existing economic model. At the very least, as Baroness Altmann says, "this takes long-term planning, which does not fit well with short-term political cycles".

If governments are not tackling these long-term challenges, how does the individual plan financially? While AI is becoming more important within wealth and investment management, it’s less about human versus machine and more about how human and machine work better and faster together. For pensions and other financial advice, human agency and choice will continue to be central. As life becomes more complicated, people will need complex and holistic advice more than ever before.

What, then, direction will this advice likely take? Paul Jackson, global head of asset allocation research at Invesco and author of The 21st Century Portfolio, believes this is shaped by four key factors: low bond yields, demographics, climate change and technological innovation. "The age at which we retire and our lives thereafter are impacted by, for example, the fact that bond yields are so low," he says. "By selling down the assets instead, you are effectively doing what an annuity would do, but hopefully getting a much better return."

Joachim Klement, head of strategy at investment bank Liberum Capital, agrees that bond yields are "permanently down", but he believes that premising any alternative strategy on demographic trends is "nearly impossible". He says, "Demographic changes happen very slowly. You have a 20- to 30-year trend that is overlaid by three-, four-, five-year events, where investors are attempting to follow a signal that is five times smaller than the noise in the market."

Joachim Klement, Head of strategy at investment bank Liberum CapitalDemographic changes happen very slowly. You have a 20- to 30-year trend that is overlaid by three-, four-, five-year events, where investors are attempting to follow a signal that is five times smaller than the noise in the market.

Nevertheless, we are already confronted with a society that is older than a generation ago, and getting older. For Baroness Altmann, this creates a whole set of needs for the aging, whether for personal services such as "physical or mental health, keeping fit, beauty and skin management", or financial ones. She cites as an example of the latter mortgages that help people borrow into later life and assume their pension income is an adequate substitute for employment income. Although these exist, they are expensive relative to the other products on the market, "and I don’t believe they reflect the low risk of older borrowers relative to those of younger ages".

As Mark Twain said, it’s difficult to make predictions, particularly about the future. However, key drivers are already unfolding, such as aging populations, climate change and the technological revolution. The question we still have to resolve is how these translate into financial pathways to longer but no less enjoyable lives.

.jpg)

Human ingenuity is clawing back territory from the Grim Reaper. That comes with a new set of challenges for our species.

Investors are focusing too much on certain sustainability areas, without paying attention to the broader—or even counterproductive—effects.

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.

Produced by (E) BrandConnect, a commercial division of The Economist Group, which operates separately from the editorial staffs of The Economist and The Economist Intelligence Unit. Neither (E) BrandConnect nor its affiliates accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any party on this content.