Taking stock of the green rush

Investors are focusing too much on certain sustainability areas, without paying attention to the broader—or even counterproductive—effects.

.jpg)

Even if you’ve not watched the Ingmar Bergman classic film, The Seventh Seal, you’ll likely have seen the black and white images of a knight playing Death at chess. Set amid a plague, it is the classic cinematic metaphor.

Today, if we haven’t quite beaten death, we are a couple of pawns up, aided by technology. Death is no longer pitted against a fallible medieval knight, but battles Deep Blue, the first computer to beat a chess grandmaster.

“We’ve optimised sanitation, we’ve optimised combating infectious diseases. What are we going to do next?” asks Eric Verdin, president and CEO of the Buck Institute For Research on Aging.

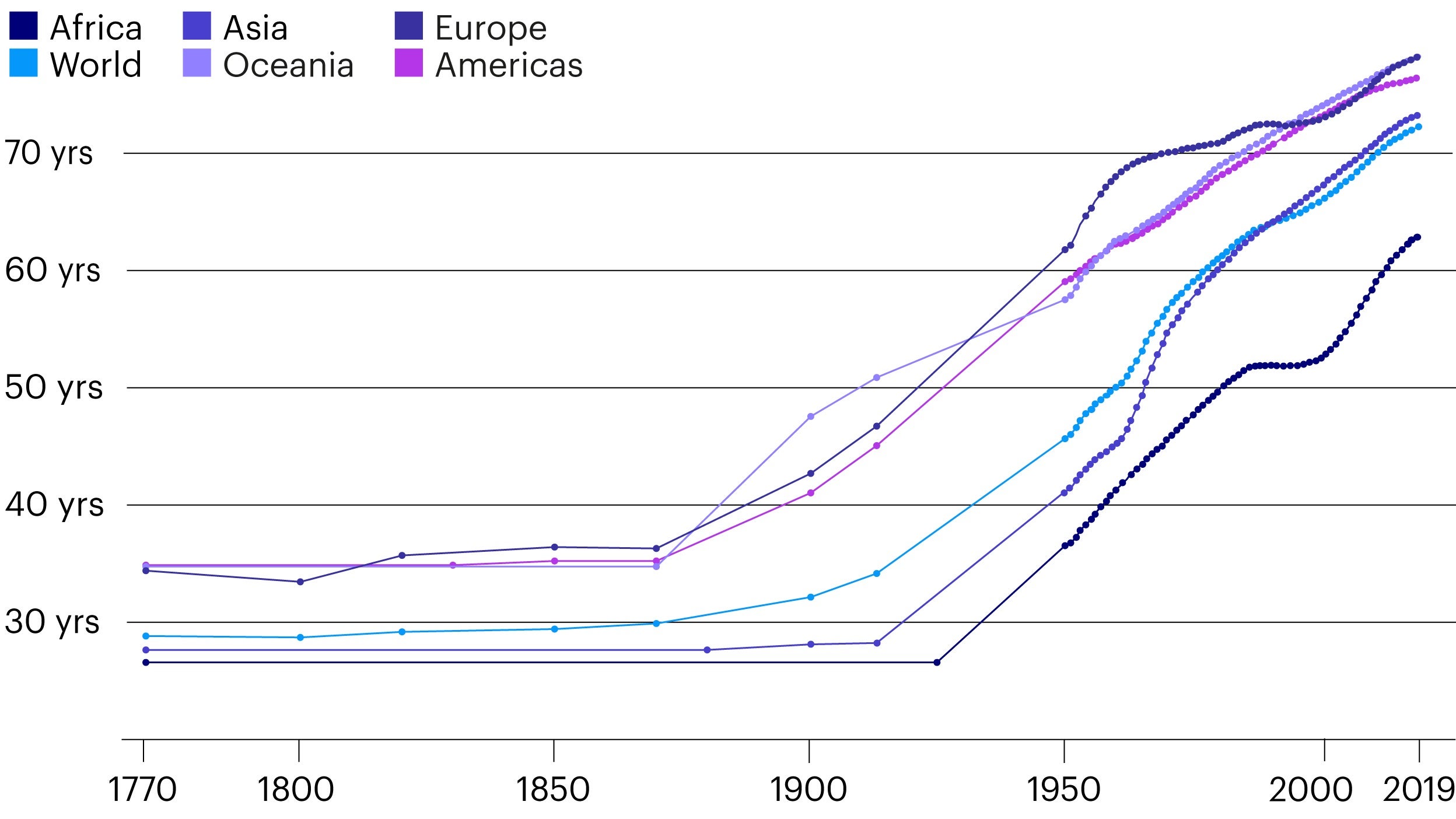

Developments in gene therapy, oncology and more mean that we’re living longer. Global average life expectancy increased by more than six years between 2000 and 2019, while healthy life expectancy has also increased.1

“We’ve seen these tremendous improvements in infant and midlife mortality,” says Andrew Scott, professor of economics at the London Business School and cofounder of The Longevity Forum. “Now, we’re tackling age-related diseases.”

Examples of treatments for age-related diseases include diabetic drug Metformin, which some doctors believe may also protect against cancer, Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease, extending life in the process. Also, anti-senescence drugs, which target the decline of old age at the cellular level, hold promise.2

And, smaller even than the cell, there are treatments that work at the genetic level. From gene editing, through growing new body parts, to smartphones that can diagnose mental health problems, technologies are pushing forward the frontiers of the human lifespan—an area of increasing interest from both a healthcare and economic perspective.

“One pandemic that is coming is that of age-related diseases, which is far and away larger and greater than what we’re seeing with covid-19,” says Professor Scott. Such illnesses include heart disease, strokes and the plethora of cancers that beset us as we creep from one decade to the next.

Tackling those, he says, will require government funding on longevity research, “which still gets a sliver of the money compared to what goes to most other diseases”.

Andrew Scott, Professor of economics at the London Business School and cofounder of The Longevity ForumOne pandemic that is coming is that of age-related diseases, which is far and away larger and greater than what we’re seeing with covid-19.

Pharmaceutical companies are largely focused on mitigation of specific aspects of age-related diseases, such as osteoarthritis and dementia, rather than curing them, which is still a long way off for some diseases. In addition, insurers are more familiar with reimbursing established treatment types than innovative ones like curative gene therapy, which are often considered too expensive (despite being one-time costs and not life-long treatments). To shift focus, business models would need to change.

Although mitigation of these diseases does help to extend life, extending lifespans is not the focus of the industry. Instead, the industry is structured around disciplines such as genetics, oncology and so on.

At the Buck Institute For Research on Aging, however, half of the nonprofit’s funding comes from the US’ National Institutes of Health (NIH). Says Dr Verdin: “The NIH has an institute called the National Institute of Aging, which I believe is now the third largest of all the institutes because the NIH has recognised that ageing is a risk factor for disease. While it’s great to have a National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute, and the National Eye Institute, all of these chronic diseases of ageing are not organ-specific; they affect pretty much every organ.” It’s this broad view—dealing with old age as a whole, rather than the particular afflictions associated with it—where Dr Verdin gets excited about the prospects for such treatments as Metformin and anti-senescence drugs to increase longevity and the quality of old age. He also references “a whole group of drugs that are mimicking calorie restriction, because we know that one of the oldest tricks you can do in animal models to make animals live longer is to restrict the amount of food intake by 20–30%”.

Ageing, doing it well and how the benefits of this are distributed imply significant structural changes in society. If left unchecked, will these innovations exacerbate growing inequalities, within and between countries? Or, as Dr Verdin puts it:

Eric Verdin, President and CEO of the Buck Institute For Research on AgingThe number one predictor of your life expectancy is your zip code.

Will all people and countries have equal access to ageing therapies? Or will it be like covid-19 vaccine access, where rich countries have hoarded treatments at the expense of poorer ones?

Professor Scott contrasts the situation now with the progress made in public health over the preceding century: “That was a massive public health campaign—tackling housing, education, sanitation—that ensured it wasn’t just the rich who benefit from those gains, but everyone.” He believes societies need to do the same thing again now for supporting longer lives, warning “if we don’t, we’re going to see inequality grow”.

Which begs the question: how will we pay for this? Thinking in terms of revenue has framed our thinking since the first industrial revolution. But money hasn’t always been the measure of all things, and some believe that it may not be the optimal measure for the future.

Thinking in terms of revenue has framed our thinking since the first industrial revolution. But money hasn’t always been the measure of all things, and some believe that it may not be the optimal measure for the future.

For Professor Scott, the answer is in reframing how we measure success. He argues that societies should start to focus much more on healthy life expectancy as a key measure for governments, rather than GDP. “That would then give society a much greater focus on levelling up the inequalities in life expectancy, because it should be a lot easier to get someone who’s dying at 50 up to 80 than it is from someone who’s 80 up to 100.”

Investors are focusing too much on certain sustainability areas, without paying attention to the broader—or even counterproductive—effects.

How can we ensure that the combination of slowing growth and longer lifespans won’t lead to poorer lives?

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.

Produced by (E) BrandConnect, a commercial division of The Economist Group, which operates separately from the editorial staffs of The Economist and The Economist Intelligence Unit. Neither (E) BrandConnect nor its affiliates accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any party on this content.