Markets and Economy Will high tariffs push the US into recession?

As a trade war rages, a massive market sell-off in the US and around the world raises many questions for investors.

New administrations come and go, but the debt ceiling is eternal. The United States has reached its spending limit and has reverted to extraordinary measures to meet its obligations. The X-date, past which the government can’t pay its bills, could arrive as soon as March. What is the debt ceiling? How does it relate to the budget process? And what happens if we pass the X-date without a solution?

The debt ceiling is the legal limit on the total amount of federal debt that the US government can have outstanding. It was devised in 1917 to save Congress from having to approve each debt issuance in a separate piece of legislation. It allowed the issuance of individual bonds without congressional approval, under a certain debt limit (with caps for different debt categories). It was intended to make debt issuance easier and give the US government greater flexibility. Congress went one step further in 1939, aggregating all debt covered under one debt ceiling.

The debt ceiling is a separate law from the federal budget law, which sets out spending and expected funding from tax revenue — a separation that is unique among major economies. The debt ceiling can conflict with the budget law depending mainly on economic growth, employment, and inflation, which drive tax revenue and spending along with the budget law itself. Variations across the budget and debt ceiling laws can put the US Treasury in a bind — should it faithfully execute the budgeted spending and violate the debt ceiling, or honor the debt ceiling, which can mean holding back on other spending commitments?

The debt ceiling increased from $45 billion in 1939 to $1 trillion in the early 1980s. By the late 1980s, it was nearly $3 trillion and kept growing from there. By the late 1990s, it was nearly $6 trillion, and it rose to $12 trillion by the end of the 2000s. Today, it stands at $36.1 trillion

The debt ceiling has been raised more than 100 times since the end of World War II, under Republican and Democratic administrations, and it was long seen as a routine task. However, it has become more divisive in recent years, with many disputes around debt ceiling increases. We saw a big debate over the debt ceiling in 2011, which prompted Standard & Poor’s to downgrade the credit rating of the United States government for the first time in the country’s history and resulted in the Budget Control Act of 2011.

Beginning in 2013, we saw less political acrimony around the debt ceiling, with lawmakers suspending the debt limit rather than increasing it by a specific dollar amount. Then in 2021, the debt limit was increased (not suspended) twice. That formally increased the debt ceiling limit to $31.381 trillion. It was increased again in January of 2025.

The X-date is when the US government will exhaust its extraordinary measures and be unable to pay its obligations in full and on time. It’s an estimate, and that estimate can change based on tax revenues, disaster relief funding, and other factors. The X-date could arrive as early as March but seems more likely to arrive later in the spring or summer.

The federal government would be forced to prioritize payments since it wouldn’t have enough money to meet all its obligations. It could delay salaries for federal employees (including members of the military), as well as payments to vendors and other so-called “discretionary spending” items that are approved by Congress through the budget appropriation process on an annual basis.

If the debt ceiling weren’t addressed for long enough, it’s even conceivable that to keep honoring debt interest payments, the Treasury could delay entitlements and other mandated spending. That could include Social Security payments, which are considered set in stone and not negotiated as part of the annual budget process.

The Treasury hasn’t been crystal clear whether it has the technical capacity to prioritize payments, but most members of Congress seem to believe it can and would do so (and we would agree with this view). There hasn’t been a modern version of prioritization in the US, though there have been several government shutdowns. However, many other governments across a wide range of emerging markets — including Russia, Venezuela, Argentina, and Pakistan — have repeatedly prioritized payments and run up arrears to employees and suppliers, which suggests that the US Treasury could as well. Alternatively, the US could delay payments on its outstanding debt; this would constitute a default, and it would be the first event of default in the history of the US Treasury.

A default would likely result in a significant downgrade in the credit rating of US government debt. But it could have far greater consequences, rippling through global markets. We’d likely see a worse scenario than 2011, with a significant stock sell-off while there’s a flight to perceived quality — in 2011 the flight was largely to US Treasuries and the US dollar although this time around it seems more likely the flight would be to gold and safe haven currencies. In 2011, the X-date was never reached, and the US certainly didn’t default on its debt obligations. If there were an actual default, it seems unlikely there would be a flight to US Treasuries. In our view, gold would probably be a major beneficiary, as well as the yen, Swiss franc, and of course the US dollar.

If US debt were downgraded enough, there could be a meaningful increase in yield as US Treasuries sell off — that would be required for the additional risk investors would be taking on. Increased interest rates on mortgages, credit cards, car loans, and business loans would likely follow. There’s also the possibility that yields could move lower if the downgrade is relatively modest and growth and inflation slowed significantly (largely what happened in 2011).

With contributions from Arnab Das and Jen Flitton

As a trade war rages, a massive market sell-off in the US and around the world raises many questions for investors.

With policy uncertainty rattling markets and consumer sentiment, it’s important to remember the market's long-term growth throughout its history.

There are signs of softening global growth prospects and rising economic policy uncertainty, plus a tectonic shift in fiscal stimulus around the globe.

Important information

NA4192281

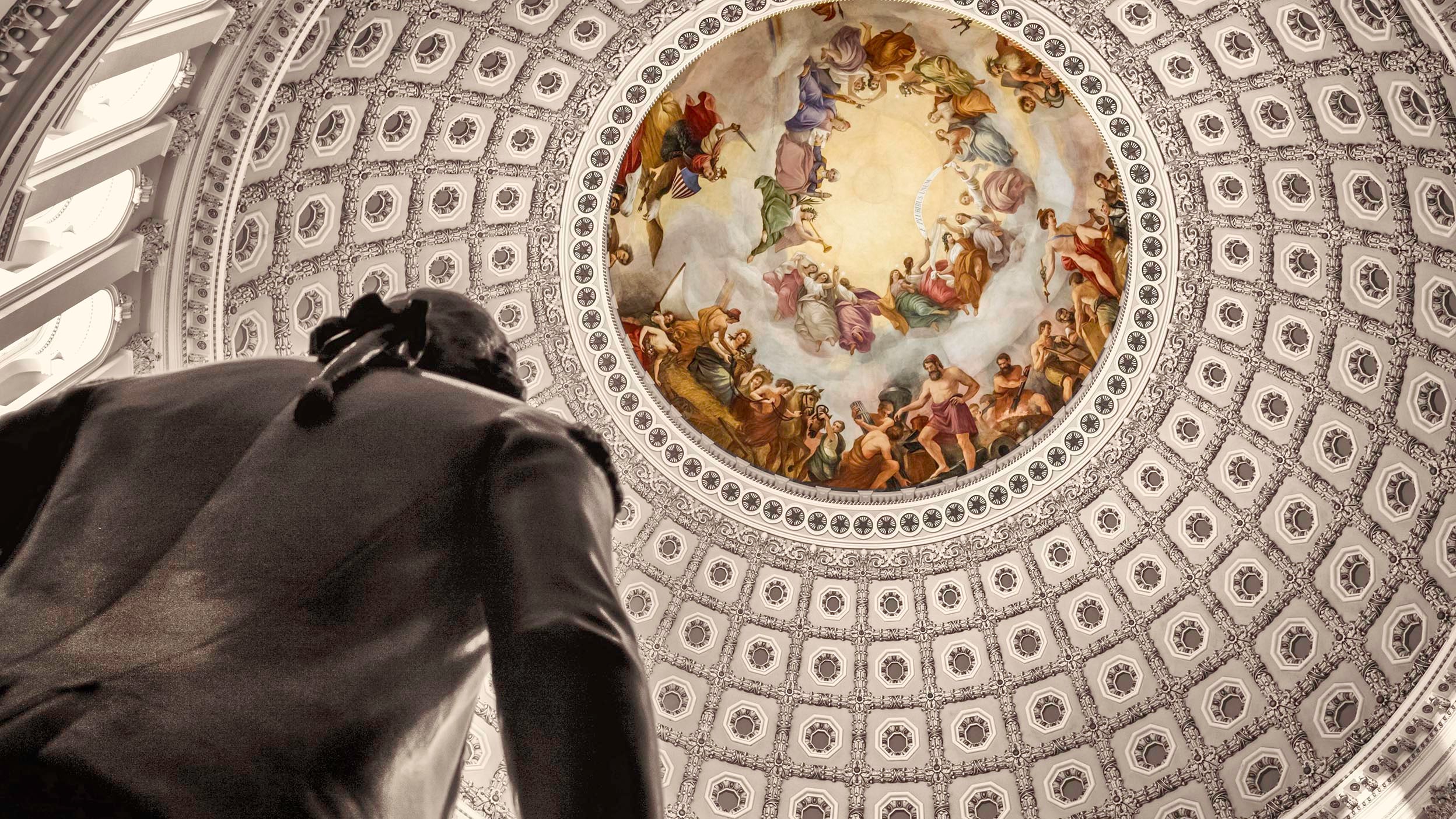

Header image: dkfielding / Getty

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

This does not constitute a recommendation of any investment strategy or product for a particular investor. Investors should consult a financial professional before making any investment decisions.

All investing involves risk, including the risk of loss.

An investment cannot be made directly in an index.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

Fluctuations in the price of gold and precious metals may affect the profitability of companies in the gold and precious metals sector. Changes in the political or economic conditions of countries where companies in the gold and precious metals sector are located may have a direct effect on the price of gold and precious metals.

The dollar value of foreign investments will be affected by changes in the exchange rates between the dollar and the currencies in which those investments are traded.

Safe havens are investments that are expected to hold or increase their value in volatile markets.

The opinions referenced above are those of the author as of February 12, 2025. These comments should not be construed as recommendations, but as an illustration of broader themes. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future results. They involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions; there can be no assurance that actual results will not differ materially from expectations.

This link takes you to a site not affiliated with Invesco. The site is for informational purposes only. Invesco does not guarantee nor take any responsibility for any of the content.