Are inflation hawks flying blind?

At our recent webinar on inflation, John Greenwood, Arnab Das and David Millar gave an update on their latest thoughts on the subject. To find out more of their views, please read these Q&A blogs.

Will the world switch from the “lowflation” of recent decades to structurally higher inflation? Will we transition from the lockdown-led Great Compression of 2020-21 via the vaccine-led re-opening now unfolding, with pent-up demand jump-started and growth turbo-charged by monetary and fiscal stimulus strong enough that inflation breaks out?

The answers to these questions almost certainly hold the key to the trajectory of bonds, stocks, currencies, as well as commodities.

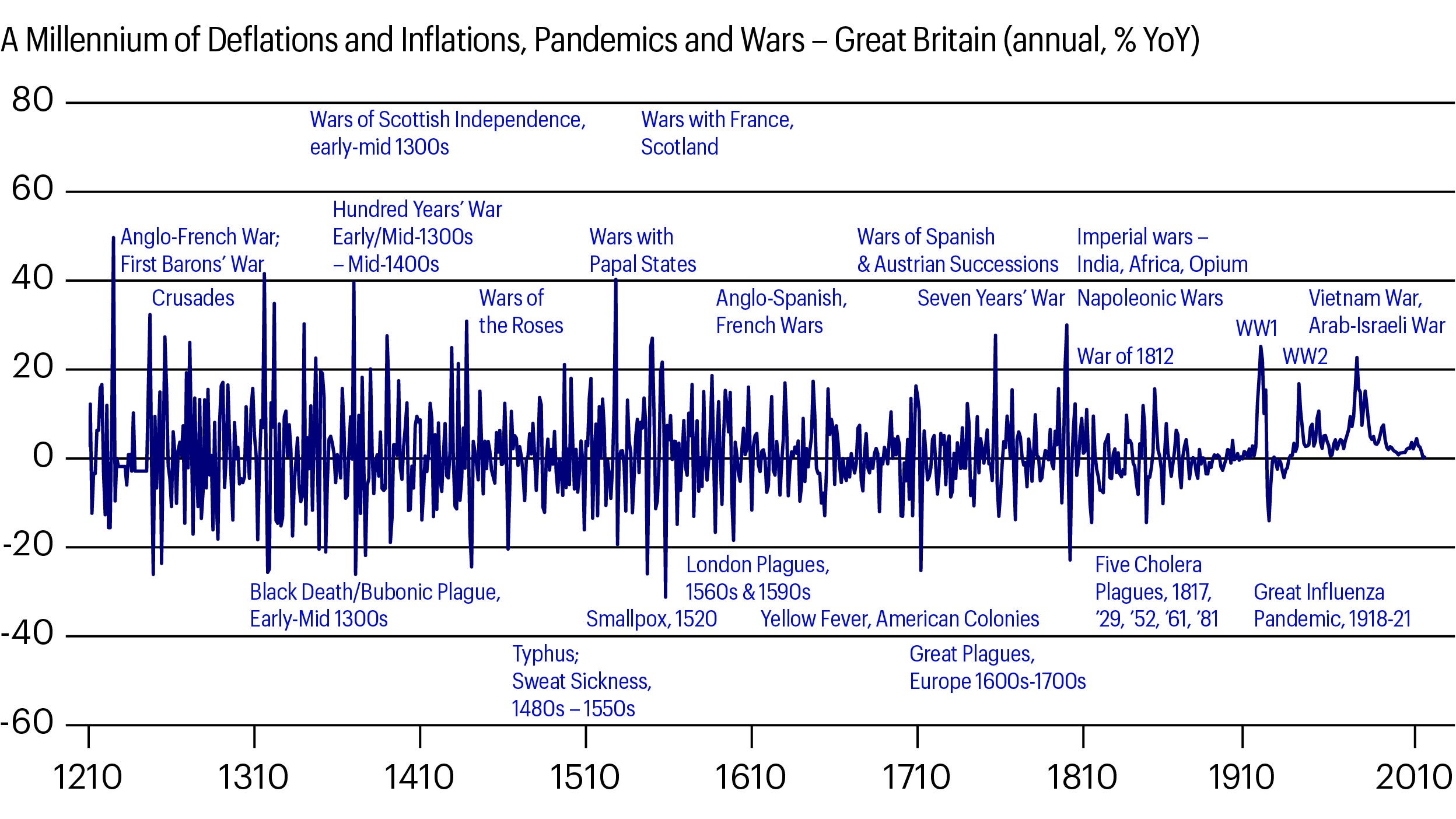

Invesco has been debating inflation risks extensively, which exemplifies our strong diversity of views. As an alternative angle to the monetarist view (that extreme money growth will lead to high inflation) or the Keynesian view (that fiscal policy needs to step in for weak private demand to avoid deflation), it’s worth turning to the real-world, long-term experience of the big inflations and deflations, laid out in figure 11.

History shows that for almost a thousand years, pandemics have been deflationary and wars inflationary. This is based on British experience, the country with the longest data, and a period covering many deflationary pandemics and inflationary wars.

This isn’t to say that the world of today is the same as the world of the last millennium – clearly, the global economy, public health systems, fiscal, monetary and financial systems are all completely different than they were in the distant past. Nor is it to say that deflations always owe to pandemics (or inflations to wars). Yet, pandemics have generally been deflationary and wars, almost always inflationary.

Still, pandemics throughout history have required social distancing and lockdowns. Severe past pandemics caused proportionally far more deaths than COVID-19, and therefore resulted in more demand destruction and deflation – largely because health systems and science were much less advanced, and because there was far less fiscal or monetary support in past episodes.

The British experience of pandemics may well offer a rough and ready guide. Pandemics destroy demand (usually, faster and more extensively than they damage supply), whereas wars boost demand, through mobilization and fiscal stimulus – often with inflationary, monetary financing – as they destroy supply.

Two other themes also come through. Inflation has shown enormous volatility over time, with few sustained trends2. Inflation volatility was lower in the 20th century than before, with fewer major pandemics or wars. But those that did occur were accompanied by severe deflations and inflations. This suggests that the right policies can cope with deflationary or inflationary shocks, reducing macroeconomic volatility and providing a more stable decision-making environment for firms and households, and thereby improving financial backdrop for investing in risky ventures and risk assets.

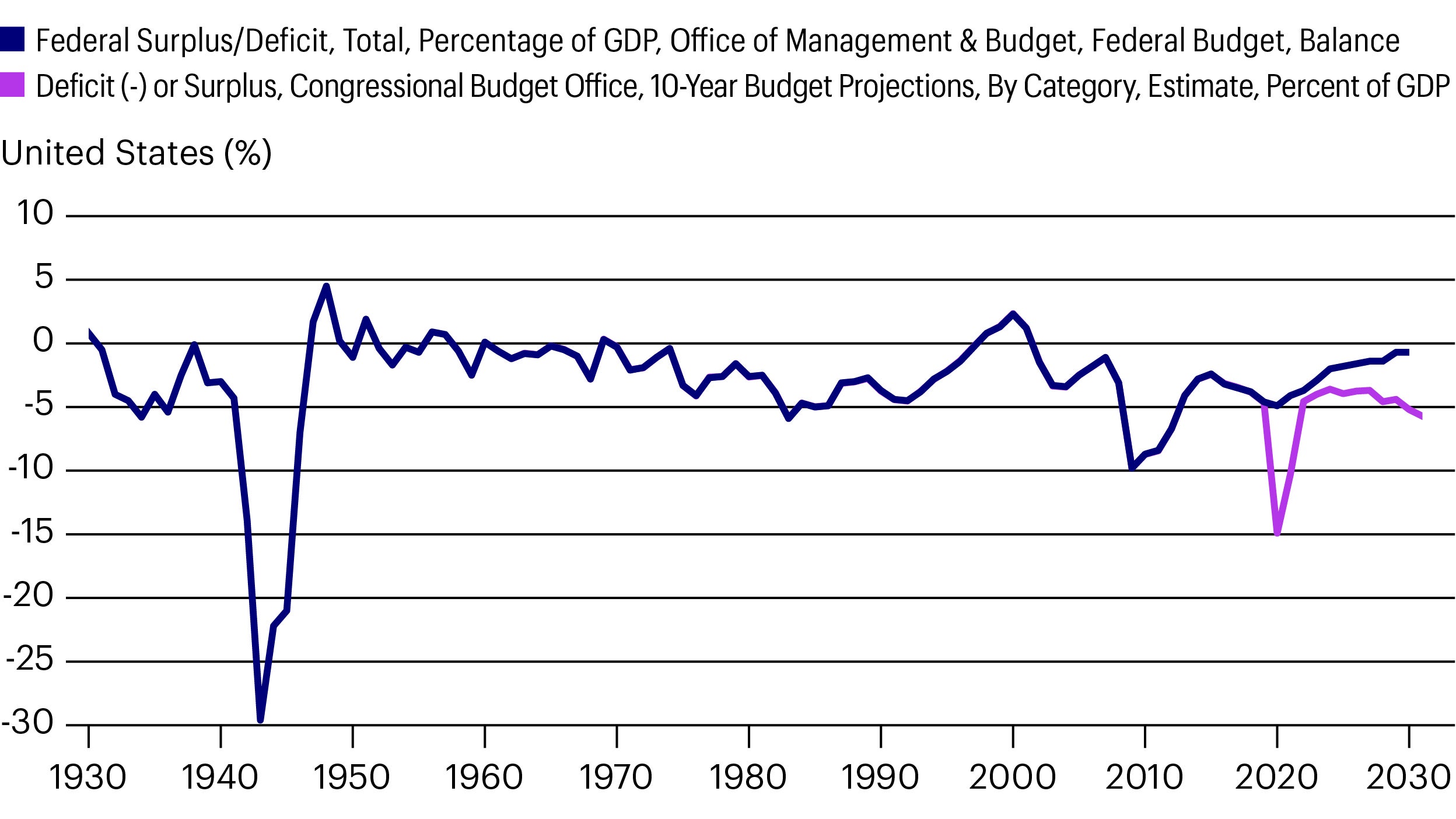

This pandemic is clearly going to be different. Deflation is already being avoided, thanks to monetary easing and fiscal transfers and guarantees, preventing collapses in economic activity, financial markets as well as employment and the activity of firms. But even in the US, where concern is strongest about inflation, fiscal support is unprecedented in peacetime. However, official estimates remain below the scale of major wars.

This combination of demand compression with monetary stimulus and unprecedented fiscal transfers and support may mean that reflation is the most likely outcome, perhaps with roughly balanced risks of inflation and deflation. It may seem that inflation risks outweigh deflation risk, given such massive monetary and fiscal support. Yet, the spread of new viral variants may prevent full economic take-off, since continued regional lockdowns or delays in full re-opening, particularly of hard-hit service sectors like tourism, hospitality and leisure as well as business travel may continue.

The policy implication is that central banks should be taken at face value – policy will remain very accommodative for an extended period, even if there is some increase in inflation or further tightening in unemployment with a strong economic recovery.

From an investment point of view, with the risks of deflation reduced and the chances of higher inflation through monetary and fiscal support, the result is likely to be a tempered rise in bond yields, with some but not excessive pricing of higher inflation amid continued outperformance of stocks and other risk assets or regions associated with economic re-opening and normalization. This will come at the expense of technology, growth and China and the US, which have benefited from low yields and lockdowns.

This backdrop also argues for rebalancing portfolio insurance from deflation defensives such as gold and perceived safe assets like long-term government bonds, to inflation insulation such as shorter-term, higher cashflow assets. Such a combination is likely to be useful as growth rebounds, the economy recovers and inflation rises meaningfully but not excessively, and bond yields rise.

At our recent webinar on inflation, John Greenwood, Arnab Das and David Millar gave an update on their latest thoughts on the subject. To find out more of their views, please read these Q&A blogs.

In 2020, gold was one of the most sought-after assets in the world as investors wanted to cushion their portfolios from volatile equity market and economic uncertainty. Now that we’re hopefully entering recovery, can gold be a hedge against inflation?

1 The Bank of England’s ultra-long-term macro- history database, A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data offers a treasure trove of data stretching back up to about a thousand years. Of course, this database is limited mainly to Great Britain, and both the UK and global economies have changed beyond recognition just over recent decades, let alone centuries or a millennium. Nevertheless, the data provides an exceptional perspective over long periods of structural economic change. In addition, over much of the period in the database, Britain was on a gold standard (or some variant).

2 Rising inflation was sustained through the mid-1600s, probably reflecting the discovery of vast new gold deposits and hoards in Latin America which contributed to rapid increases in money supply as well as fuelling financial asset price bubbles.

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Data as of 15 May 2021 unless stated otherwise.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.