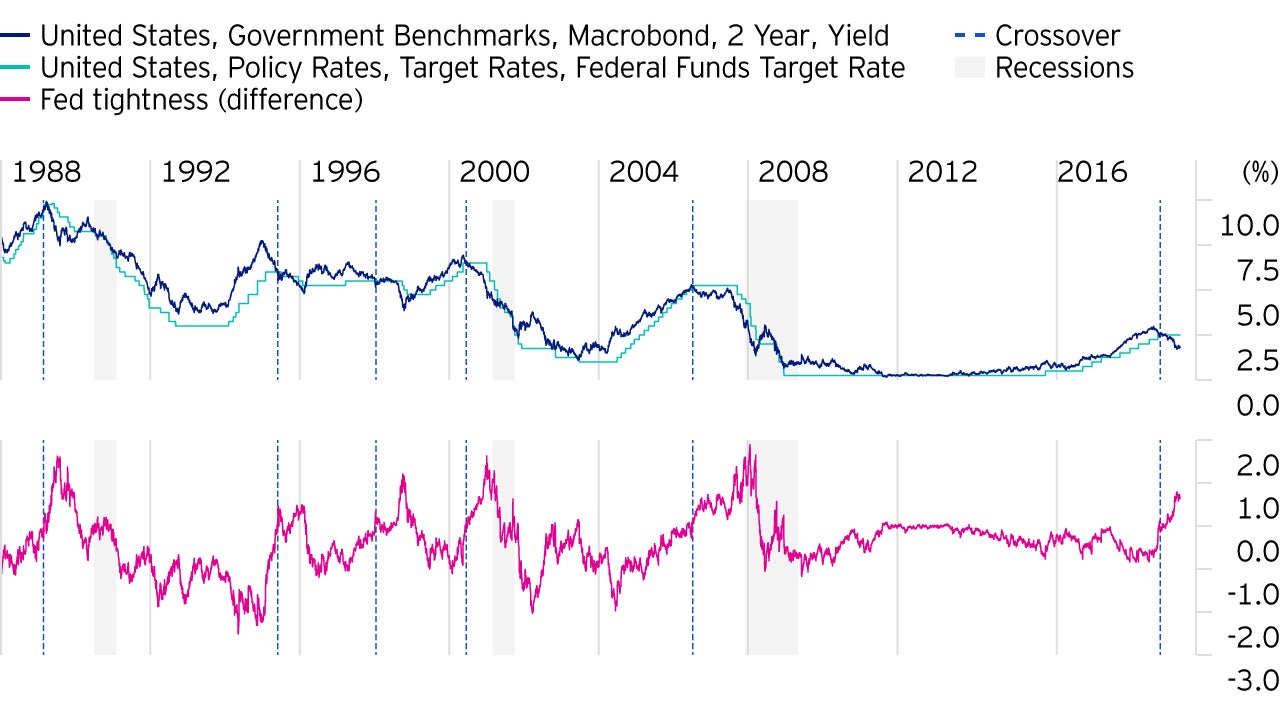

We are now facing an interesting fork in the road. After a rally in the 2-year bonds of similar magnitude to the 1995 and 1998 crossover events and with about 75bp of rate cuts priced in, where do we go from here?

Credit growth will need to pick up again

If a growth environment is to persist in the US, then credit growth will need to pick up again. Recently, money growth (M2) and bank lending have been growing at about 5% year-on-year, levels that are traditionally seen around recessions. It doesn’t help that the senior loan officers survey (on loan demand) remains downbeat.

Apart from loan demand, we have also focused on whether banks have the capacity to lend. Their balance sheets are constrained by legislation (Basel 3) but also, for the investment banks, by actions of market participants.

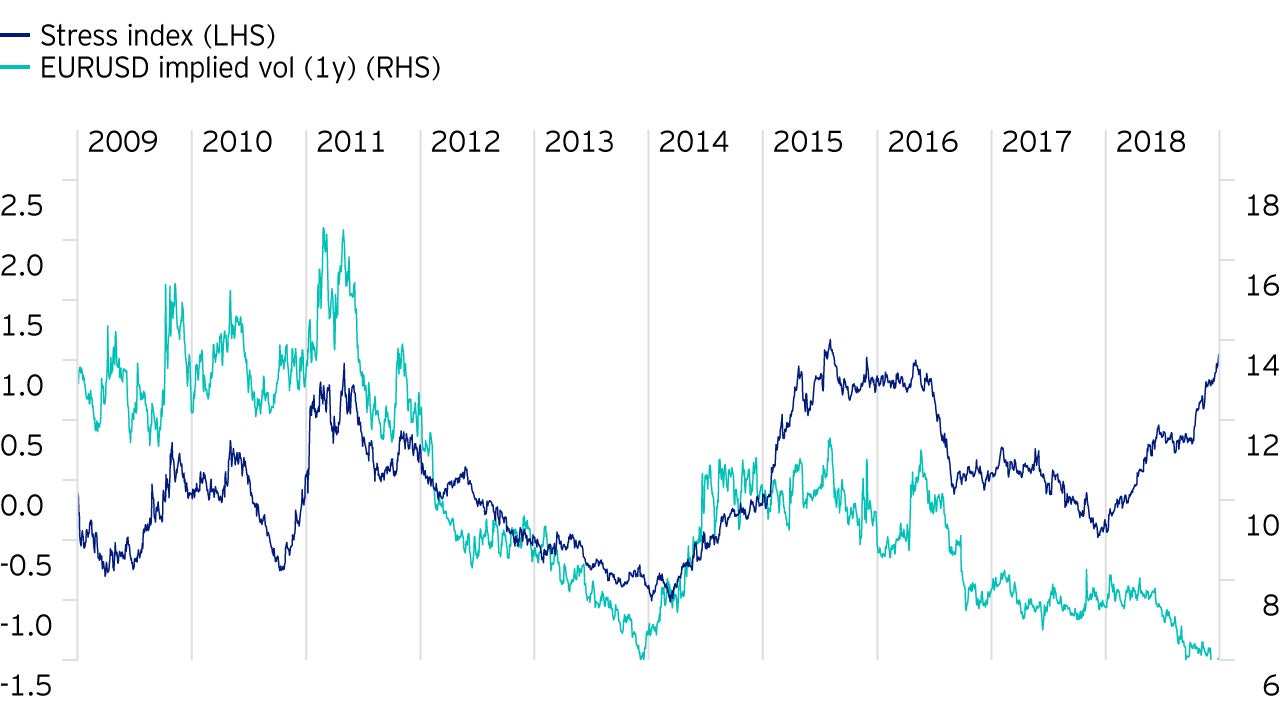

For example, if a counterparty sells them a cash bond it takes up space on their balance sheets that might otherwise be used for lending. These constraints manifest themselves in market pricing, so, for example, cash bonds might trade cheap compared to an equivalent swap trade. We have built an index to track these constraints on behaviour across a range of markets.

This index of stress in bank capacity is, as you might expect, associated with swings in risk assets. When the index rises then, typically, sovereign bonds, the US dollar and volatility also rise while equities fall and credit spreads widen.