Mythbusting two claims about the role of central banks

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic recession, central banks around the world have been expanding their balance sheets at historically high rates.

Unfortunately, there still seems to be some confusion concerning where and how central banks fit into a modern financial sector, giving rise to a few myths.

In this short piece, we discuss two prominent myths.

Ironically, these two claims about the nature of central banks are mutually exclusive.

1. Only central banks can create money “out of thin air”.

Some economists and market participants believe that central banks and commercial banks are fundamentally different in the way that they operate, and what each can achieve in the money and credit creation process.

Some claim that only central banks can create money “out of thin air” via asset purchases - a monetary power uniquely available to central banks.

This, however, relies upon a fallacious view of banking.

A standard, textbook view of banking is that banks operate a “fractional reserve” system - that is, banks accept deposits from customers, using most of these funds to make loans to borrowers while holding in reserve a specific “fraction” of the bank's deposit liabilities.

But this is an outdated, “Jimmy Stewart” version of banking - if it was ever true.

Modern banking relies on “credit creation” - the creation of credit via loans or the purchase of securities, both of which simultaneously create deposits in the account of the borrower or seller.

This is a “power” that both commercial banks and the central bank share as banks, known in the past (and only partly correctly) as “fountain pen” money and “printing press” money respectively.

Prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks played a relative minor role in the money and credit creation process.

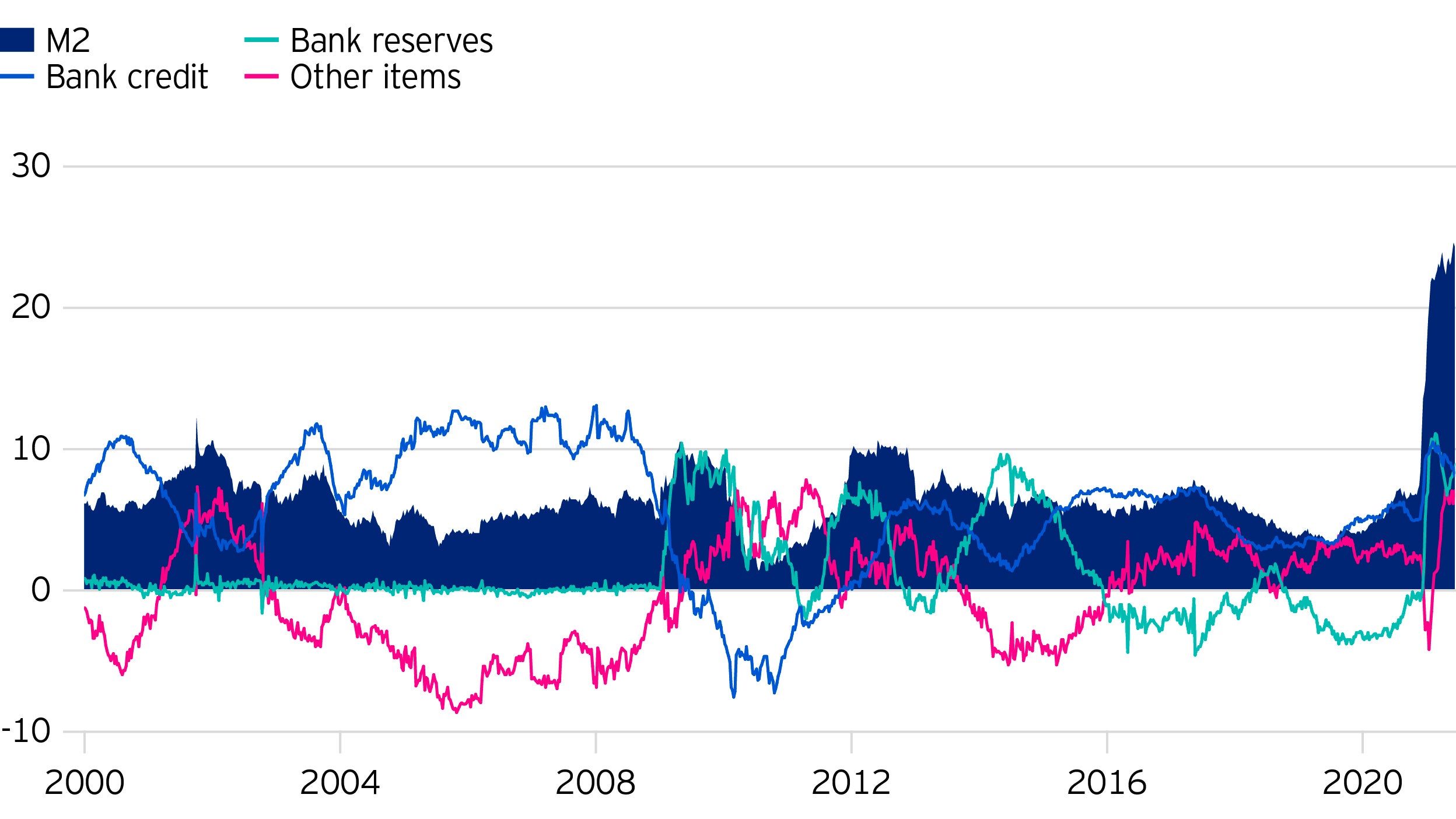

If only central banks can create money, then how did the US M2 money supply expand in the period prior to the GFC? Figure 1 provides the answer.

As previously stated, prior to the GFC and focusing on the period from 2000 to 2008, the contribution from the US Federal Reserve to overall M2 money growth was essentially zero, as shown by the green line in Figure 1.

Over the same period, the major contribution to the increases in the M2 money supply was commercial bank credit, as highlighted by the slightly lighter blue line.

The central bank only became significant in the money creation process after 2008 as shown by the three successive episodes of quantitative easing (QE) which can be seen clearly in green.

In short, Figure 1 shows unequivocally that it is not just central banks that create money, but also commercial banks.

2. Central banks can only provide loans against collateral to commercial banks and cannot influence the money supply directly.

The second myth about central banks is ironically almost the exact opposite of the first myth, namely that central banks can only affect the money supply indirectly.

To refute this claim point blank, one could point to the disastrous advances by central banks to governments in countries like Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

However, more care is needed in the modern context.

As we have explained before, the counterparty of central bank asset purchases is key.

If the counterparty is a commercial bank the resulting transaction is merely an asset swap (securities for central bank reserves), resulting in no increase in the money supply.

If, however, the counterparty is not a commercial bank, but the government, a commercial or financial company, or an individual, then the counterparty receives a new bank deposit from the central bank in exchange for the security sold.

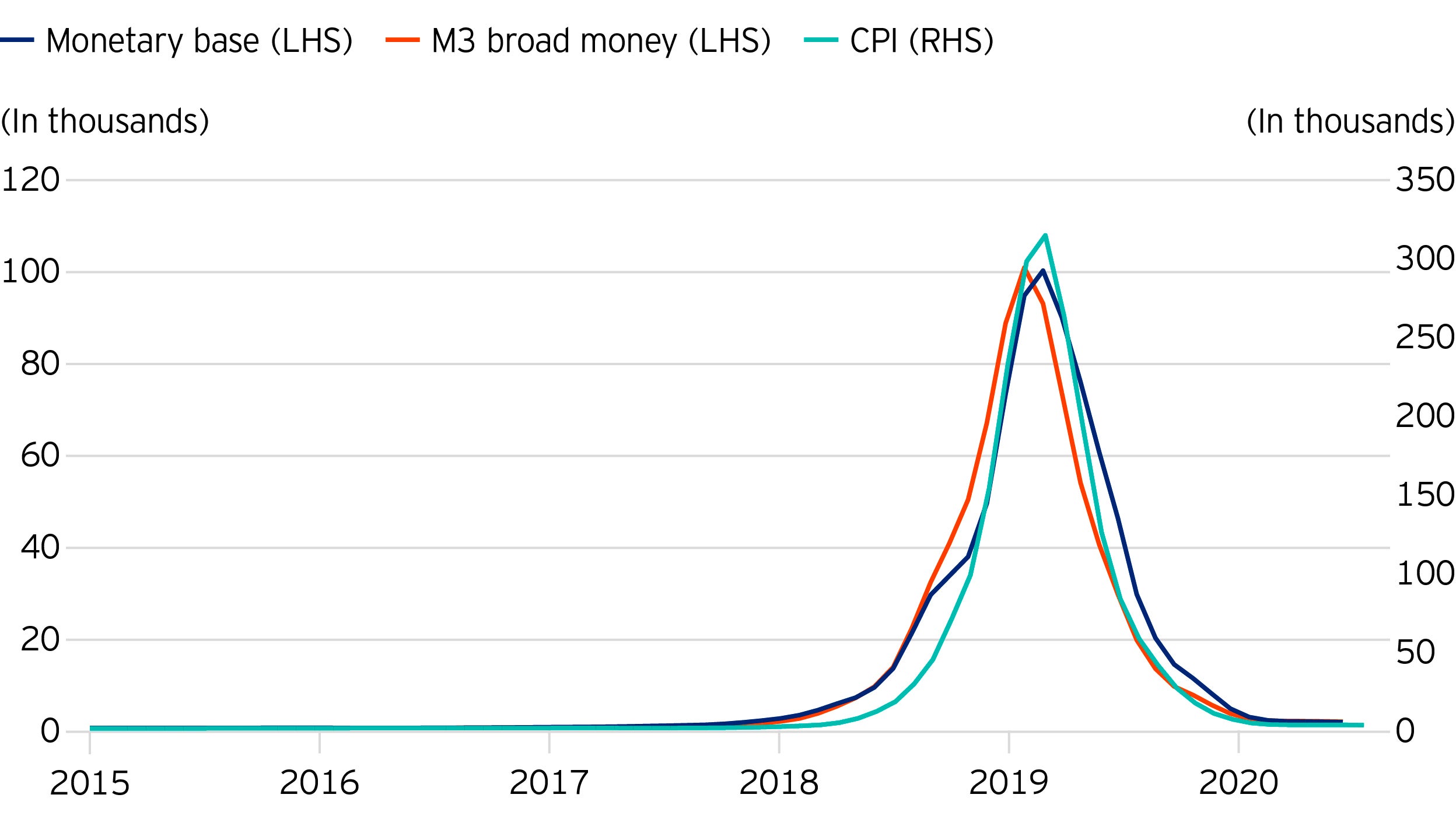

The inflationary episode in Venezuela in 2019 is a perfect case study of direct funding by the central bank and provides excellent ammunition against the claim that central banks cannot influence the money supply directly.

Figure 2 highlights the impact on inflation of the expansion of the balance sheet or monetary base of the Banco Central de Venezuela (BCV) and the broad money supply.

Starting in 2018, the BCV began to finance government spending directly, drastically increasing the cash balances of the government.

As a result, the monetary base and the M3 broad money supply both expanded hugely and almost exactly in parallel.

The coincidence in the growth rate of the monetary base and the M3 broad money supply shows that the money creation was via the central bank’s actions, which led to an extraordinary increase in CPI inflation.

Conclusion

It is vital to understand the money and credit creation process in a modern economy.

Both central banks and commercial banks play a role in the process of money creation, but which institutions are leading the process at any point in time depends on the circumstances.

For most of the decade since the GFC, intensified regulation of the financial sector has placed central banks right at the forefront.

Meantime under Basel 3 the commercial banks have been required to increase their capital ratios and observe new, stricter liquidity and leverage ratios.

These tougher rules have straitjacketed commercial bank balance sheets, effectively limiting the traditional money creation role of commercial banks that was evident before 2008.

In the face of the two global crises of 2008-09 and 2020, this has meant that, on each occasion, the baton of money and credit creation had to be passed from commercial banks to central banks.

A failure to understand the basics of money creation can lead to false beliefs about the transmission of monetary policy and mistakes in asset allocation.

For example, in the aftermath of the GFC many high-profile economists argued that QE would lead to rapid inflation.

Similarly, many asset managers positioned their portfolios for high inflation which did not materialise.

Looking forward from the present, to forecast inflation or design portfolios optimally for the future requires a clear understanding of whether and in what sense it is central bank money creation or commercial bank money creation that is driving the process.

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important Information

-

Where John Greenwood and Adam Burton have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.