The NWF absorbs the additional revenues the Russian government receives when the oil price is higher than $40 per barrel. These funds should be enough for the country to withstand economic stress, even when the oil price starts to fall.

Putin may also choose to boost his popularity through fiscal measures targeted at near-term household wellbeing. These could help the economy grow faster and make Russia’s citizens better off. Indeed, the government is set to increase spending over the next three years.

What is the impact on Russia’s currency?

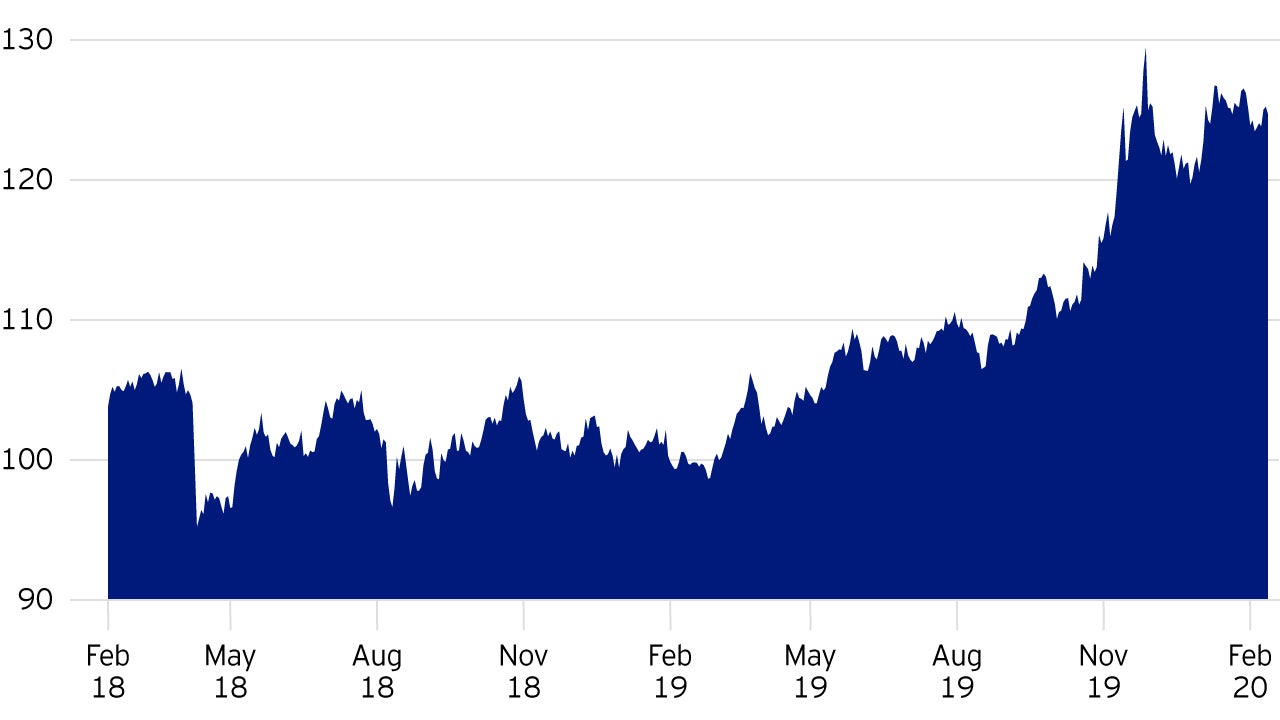

The ruble and oil have been very highly correlated – though less so recently because of the budget rule where the Russian government bought foreign currency with excess savings. Buying other currencies (and selling rubles) when oil prices are high was a further step aimed at stabilising the ruble to insulate the economy from the effects of volatile energy prices.

This tight fiscal stance has made Russia a favorite among bond buyers, among others, and has made it stand out among emerging markets, in turn helping the ruble perform strongly in recent years.

Despite historically low interest rates, the ruble remains a high carry currency, which, combined with orthodox monetary and fiscal policy and cheap valuation, makes it an appealing currency to hold.

Chile

On the other side of this trade, we have a short position in the Chilean peso. Until November 2018, we were actually long the peso, however, we have felt for some time that Chile was moving from the ‘good EM’ towards the ‘bad EM’ category.

Chile has been one of the region’s most stable, fastest growing and prosperous nations. When its billionaire president Sebastián Piñera was interviewed in the Financial Times in October of last year, he evidently took pride in describing the state of the economy.

‘Look at Latin America,’ he said. ‘Argentina and Paraguay are in recession, Mexico and Brazil in stagnation, Peru and Ecuador in deep political crisis, and in this context Chile looks like an oasis because we have stable democracy, the economy is growing, we are creating jobs, we are improving salaries and we are keeping macroeconomic balance. Is it easy? No, it’s not. But it’s worth fighting for.’

By the time the interview was published on 17th October 2019, the streets of Santiago were alight with student protests provoked by an increase in the city’s metro fare. The demonstrations swelled into a revolt against social inequality and the rising cost of living. Piñera declared a state of emergency on 18th October and deployed the army to restore order.

Even before the violence, numerous macro indicators led us to believe that Chile’s ‘safer’ status within EM was at risk. Debt levels in Chile have been worsening, with the current account deficit doubling and budget balance in negative territory.

There has also been a worrying trend in hard currency debt. It is now more than double in % of GDP terms than any other main Latin American country, which given the fall in the currency, is going to become more painful.

The unemployment rate in Chile is trending upwards and the consumer is in pretty poor shape. At the same time, confidence in the government is in freefall with President Sebastián Piñera’s presidential approval ratings dropping rapidly.

With economic data worsening, reforms being blocked and the central bank cutting interest rates to all-time lows, the Chilean peso became vulnerable. While we saw the potential for unrest, what we did not forecast is the violent protests which took place in October and November.

So, what now?

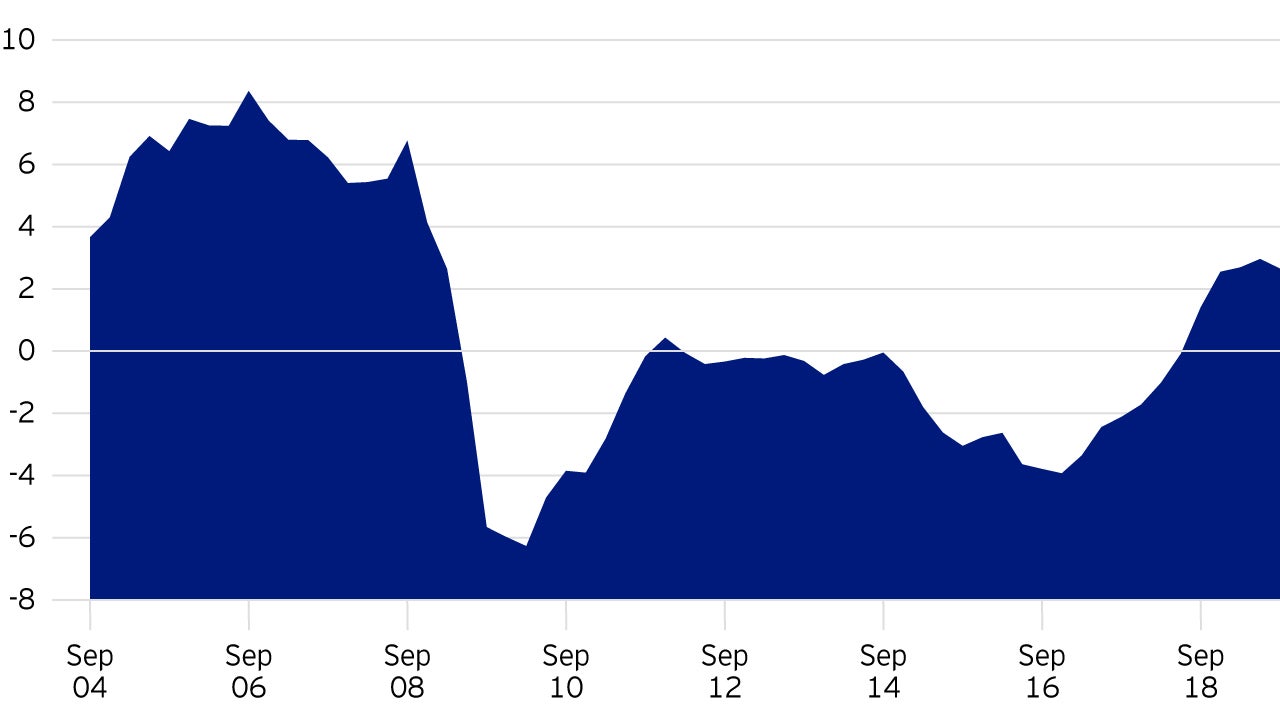

Following the large move lower in the peso (see Figure 2), we reverted back to our TEAM review process to decide what to do next.