Quarterly Global Asset Allocation Outlook | Q3 2025

Paul Jackson discusses his insights on portfolio allocations and strategies for the Q3 2025 outlook.

It may seem odd to see “Emerging Markets” (EM) next to “innovation”. The original EM investment thesis was, if anything, the opposite of cutting edge: capitalize on the release of trapped potential as EMs import existing technologies to catch up within decades to productivity, income and wealth achieved over centuries by “Developed Markets” (DMs) – as exemplified by Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Korea, and most recently, China.

However, innovation is becoming increasingly important for EMs to keep pace with DMs, given the rapid pace of technological change during the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution (or Industry 4.0), as well as the rise of trade and investment barriers.

Watch our webinar to find out how innovation is powering emerging market growth.

Some EMs have leapfrogged toward the technological frontier by adapting earlier technologies or increasingly applying home-grown innovations. For example, rougher roads, smaller public budgets and greater congestion have encouraged the use of cheaper, simpler rugged vehicles, higher public transport loads or no-frills electronics like simpler, cheaper smart phones or laptops.

What’s more, EM innovation is often intrinsically ESG-oriented. For example, Kenya adapted smartphone banking for microlending. “Aadhar” – India’s biometric identification system – “the most sophisticated ID system in history” – enables direct transfers of financial and medical support even to people without bank accounts1. Both bypass middlemen, enhance financial inclusion and sustain growth.

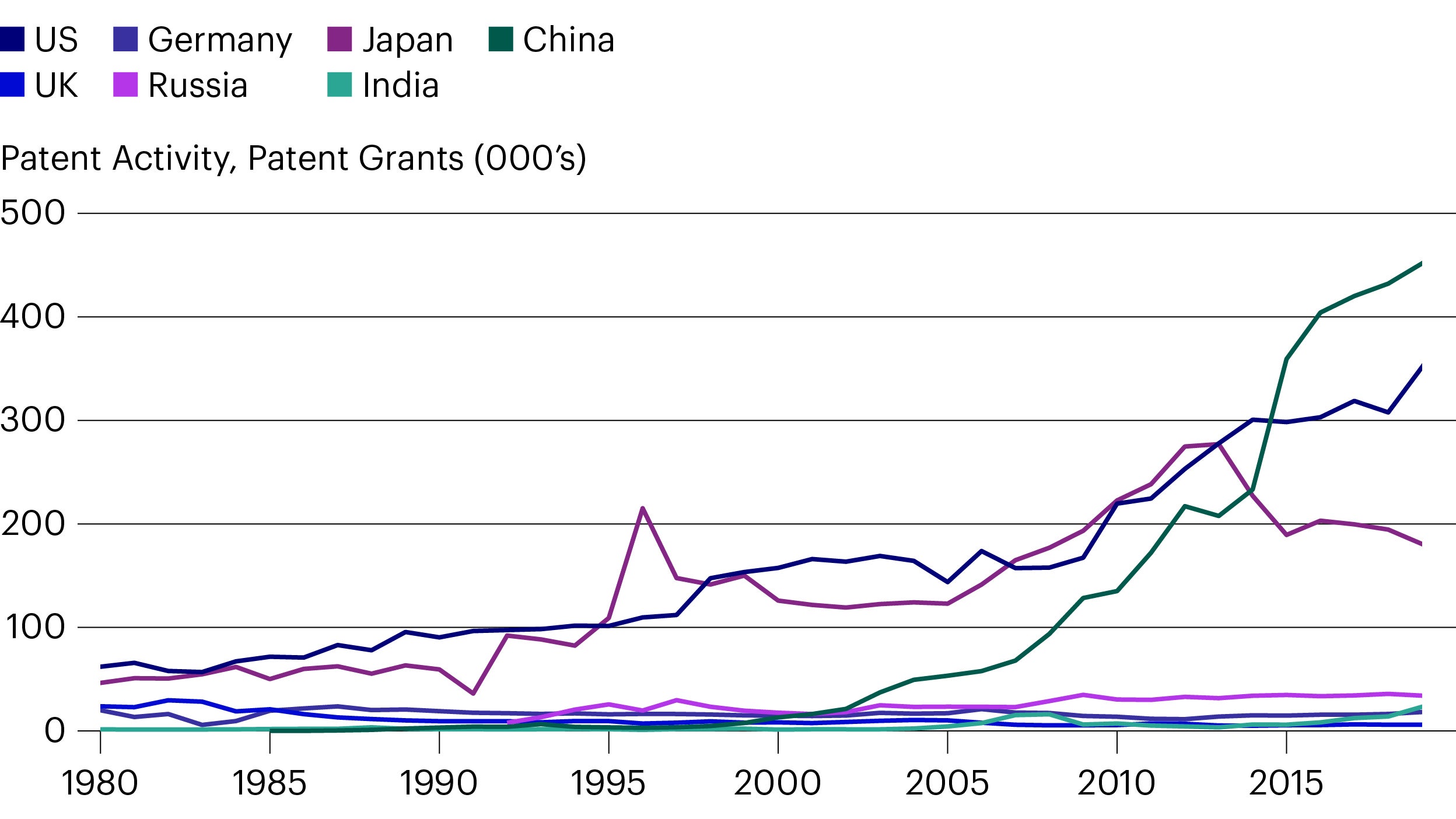

Many EMs have a storied innovation culture in both the distant and more recent past. Some are making rapid progress and winning many patents now, emphasizing their productivity potential. Uniquely among all major economies (developed and emerging alike), China combines dynamic innovation with unparalleled growth and scale. In 2014, China surpassed the US and Japan in patents, and by 2019 garnered almost 10,000 more than the US (Figure 1).

Of course, all other EMs lag China in patents – but so do all DMs. And, Russia has outpaced Germany and the UK for years; India also garnered more patents than either in 2019. But patents are not everything. Innovation must be continuously commercialized to boost GDP, productivity, profits and returns. Policies will need to be put in place to encourage innovation, protect intellectual property as well as competition.

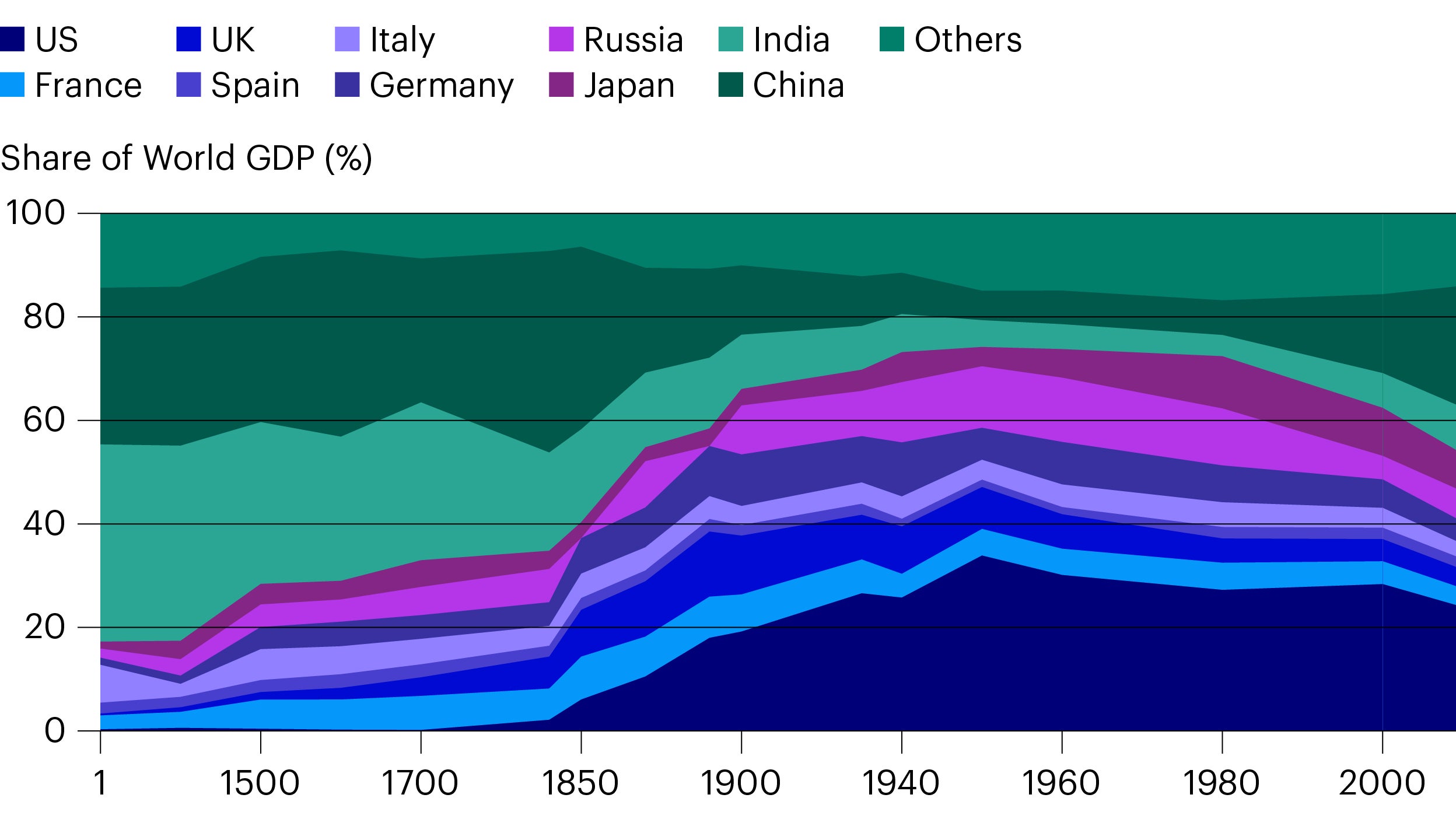

Over centuries, demographics and productivity have driven the global distribution of income and wealth, driving the destiny of nations. Two millennia of GDP data reflect the impact of technology and productivity growth, as well as demographics on shares of global activity (Figure 2).

Until about 1500 CE, India was the world’s largest economy, when China and India drew roughly even. Back then, global GDP shares boiled down to demographics, given limited innovation and similar productivity growth everywhere. Successive Industrial Revolutions accelerated shifts in global activity and wealth.

In the 1700s, China became the largest economy with colonization, de-industrialization and famines in India and industrial revolutions in Europe. In 1873, the US took the lead with rapid post-Civil War reconstruction and industrialization. After political turmoil in the 1900s, China and India turned inward, languishing in slow growth.

Three decades later, China again leapt forward in 1979, with reform, re-industrialization, reopening to global trade and capex with WTO membership in 2000, significantly raising productivity. As a result of adopting the technologies and techniques of the first three Industrial Revolutions across the economy, China has rapidly regained a large share of global activity. With financial deepening and opening from the 2010s, China’s weight in global markets has also accelerated sharply. With its long, rapid march to the technological frontier, China could become as innovative and productive as leading DMs, with commensurate economic and financial scale.

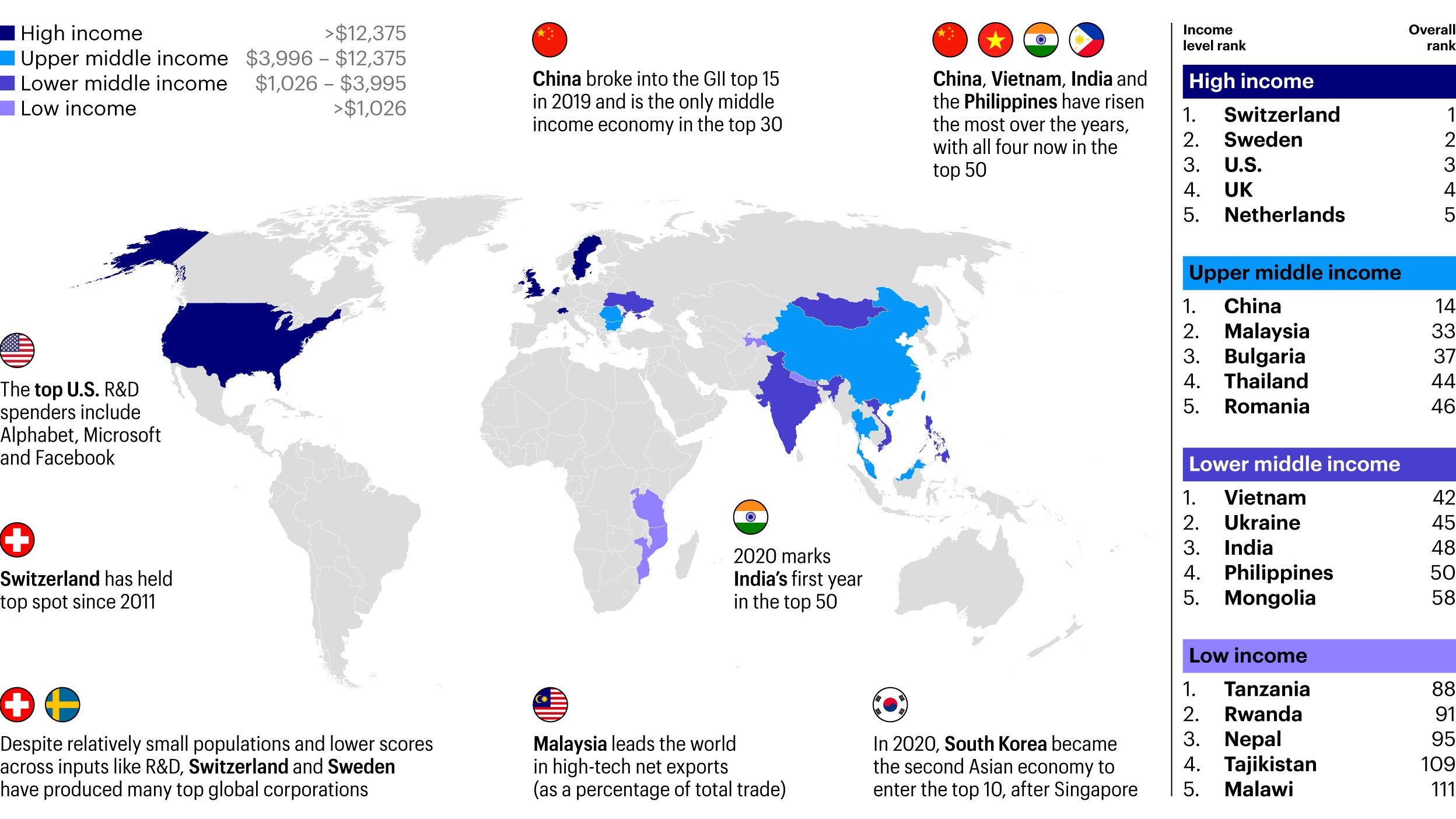

But not all EMs are created equal. No other modern EM has yet become anywhere near as innovative and effective as China, though some have the potential – scale, dynamism or strategic significance – to make their mark on the global economy, markets, and by extension, investment portfolios (Figure 3).

None of this means that EMs are destined to dominate, or DMs to decline, even in relative terms. It all depends on policies and performance. EM potential entails risks., and rapid technological, economic and societal progress can unleash that potential. Equally, the risks can cause economic turbulence, financial volatility and underperformance, as in Russia recently, or Argentina, whose economy has been in decline for over a hundred years.

In our view, distinguishing countries that strike the right balance between regulation, competition and letting markets work is likely to be increasingly important in picking and choosing EM economies that are likely to do well in facing the environmental, social and governance challenges in a challenging global economic environment.

Watch our webinar to find out how innovation is powering emerging market growth.

Paul Jackson discusses his insights on portfolio allocations and strategies for the Q3 2025 outlook.

Welcome to our Tactical Asset Allocation hub. Here you’ll find a selection of the most recent research from Invesco Solutions. Read our latest analysis that covers market strategy and opportunities across various asset classes.

We speak with IFI portfolio managers about the factors driving US investment grade and how they are navigating the current fixed income environment.