Stagflation – A Rerun of That ’70s Show?

Key takeaways

1.

2.

3.

Grappling with “Stagflation”

Stagflation fears lurk in the market pricing of above-target inflation expectations, while ultra-low bond yields point to weak growth. High inflation reflects supply bottlenecks, labour shortages, and resurgent but now slowing demand, brewing a whiff of stagflation.

Stagflation risk is central to scenario planning and portfolio positioning. A shift in the market consensus from transitory inflation to stagflation could cause financial shocks. Equally, if the Fed were too dovish for too long, fear of a sharper turn later could precipitate a self-fulfilling tightening tantrum.

Defining Stagflation

Stagflation is a miserable mix of high inflation, weak or negative growth and rising unemployment, but thankfully rare. Instead, high inflation usually accompanies high growth and employment – and vice versa.

A direct relationship between falling unemployment and rising inflation is intuitive: The stronger is demand, the easier for firms and workers to raise prices and wages – and vice versa. Financial markets are no different: JP Morgan, asked why stocks had rallied, famously quipped … more buyers than sellers.

How rising unemployment and falling growth take root with rising inflation is less clear. Firms should produce more to exploit high prices – or central banks tighten to curb demand.

Whys and Wherefores of Stagflation

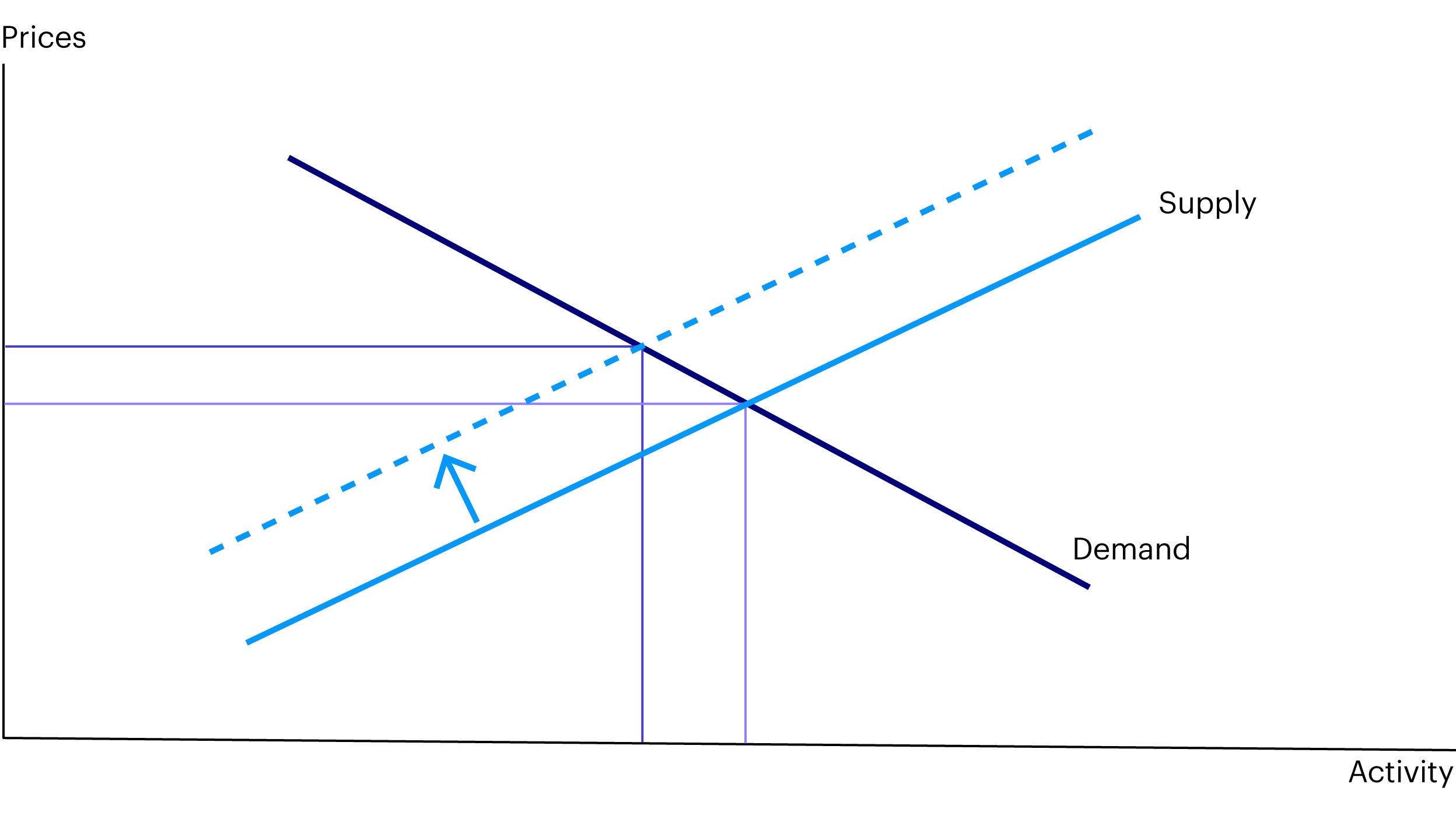

Stagflation seems to come from “adverse supply shocks” in which non-economic factors interfere with the normal workings of free markets and price signals. Supply curves normally slope upward – if prices rise, firms boost output to meet demand and enlarge profits. Demand curves slope downward, since buyers purchase more at lower prices, all else equal.

But adverse shocks would shift the aggregate supply curve in and up to the left, causing supply and demand to meet at lower output / higher price levels (Fig I). Such shifts can reflect reduced availability of inputs – e.g., regulatory controls on trade, commerce, production or labour supply via immigration, worker protection or minimum wages. Pandemics, lockdowns, financial crises, trade friction, wars or natural disasters are all capable of restricting supply (and demand).

In stagflation, monetary tightening might restore price stability – at the cost of slowing demand, further lowering growth and employment but probably without unlocking restricted supply. Instead, investment, hiring and productivity growth could slow, reducing trend growth and employment. The Fed would face a policy dilemma in prioritizing among its goals of full employment, price stability, moderate long-term interest rates, financial stability and possibly inequality, raising the risk of policy errors.

Markets could get ugly in severe stagflation. Tighter policy, slower growth, lower earnings, but higher inflation and unemployment imply losses on bonds and risk assets, pending restoration of price stability and noninflationary growth.

That ’70s Show – Not Much Comedy, Lots of Errors

Severe supply shocks – the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo and 1979 Iranian Oil Embargo – contributed to stagflation, but oil was not the only problem by any means. Free market forces were bottled up by regulation and activist public policies. Labour markets were regulated and unionized, raising the bar for hiring and expansion. Conglomerates and oligopolies limited competition, boosting pricing power. Capital controls and financial repression were widespread.

These oil shocks followed strong growth and inflation in the 1960s, deficit financing of the Vietnam War and Great Society Program, together contributing to a wage-price spiral as unionised workers secured wage rises and many firms managed to pass on cost increases. But those that couldn’t secure wage or price increases suffered, slowing growth and employment. The Nixon administration’s price controls and gasoline rationing only made matters worse. Shortages repressed consumption but boosted inflation once released.

Source: US Federal Reserve, Bloomberg, Macrobond, Invesco. Data through July 2021

Worse still, successive US presidents undermined the Fed in the 1960s-70s. William McChesney-Martin, Jr., who became Chair after Fed independence was restored in 1951, described its job as taking away the punch bowl just as the party gets going.

President Johnson, frustrated by McChesney-Martin’s refusal to stand down after hiking rates, literally attacked, throwing him into a wall. The Fed used regulation to slow credit growth, then hiked rates only after Johnson decided not to run for president again, but inflation still rose.

President Nixon notoriously insisted that he expected Fed Chair Arthur Burns independently come to the same conclusions he himself had already drawn. In 1973 Burns caved, cutting rates as inflation rose, to boost investment and employment and grow out of the stagflation problem.

President Carter brought in G William Miller, who wanted to fix high inflation and unemployment simultaneously, and resisted raising rates despite being outvoted by the FOMC. After 18 months, Carter replaced him with NY Federal Reserve President Paul Volcker, who shifted to sharp rate hikes.

Volcker stuck to his guns despite pressure from President Reagan, causing a double-dip recession surging unemployment and interest rates, but restoring Fed credibility and price stability. Reagan’s supply-side deregulation and Volcker’s tight money policy probably solved stagflation and paved the way for the Great Moderation of low inflation, and rising growth, employment and productivity.

Stagflation Here and Now?

Today’s supply bottlenecks, labour shortages and restrictions on free movement of goods, services, people and capital across borders could cumulate into stagflation. Worker protections and higher wages add cost pressures. Lockdowns, re-openings caused massive shifts in spending may contribute stagflation risk (see The Long and Short of It: Inflation or Reflation? Torturing the Data, July 2021).

But the economy and the politics are very different from the 1970s. Today, employment and investment are rising rather than weakening. Some supply constraints – like semiconductor shortages – may not be quickly solved, but suppliers are increasing capacity. Technological change and strong competition between companies, countries and workers are likely to continue. Demographics still points to ageing and shrinking populations and hence slower demand growth in many countries.

Today, the right wants free markets while the left prefers to correct market failures. Unlike the interventionist policy consensus of the 1960s-70s, this polarisation stands in the way of heavy-handed regulation.

Above all, monetary policy is moving towards normalization, rather than easing under political pressure, working against stagflation risks. Thus, the chances of mean reverting toward “the old ordinary” of gradual gains in growth, productivity and employment seem higher than than 1960s-style inflation or 1970s-style stagflation.

The Bottom Line

The most likely outcome continues to be economic recovery with moderate inflation following reopening of services and release of pent-up demand amid sudden shifts in spending and supply. But stagflation due to supply and labour shortages, high growth/inflation and disinflation following COVID-Delta, remain major risks. This outlook calls for a diversified, constructive portfolio geared to reflation, balanced with insurance including inflation-indexed bonds, disinflation hedges like long-term government bonds, as well as cash, given the risks.

Related insights

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

-

Data as of 31 August 2021 unless stated otherwise.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.