High yield credit

From delivering higher income to cushioning volatility, find out what high yield credit can bring to a portfolio.

After a dramatic market reset in 2022, the high yield market is now living up to its name. Yields and spreads in the asset class are higher than they have been for quite some time, creating opportunities for investors to lock in higher levels of income for the years to come.

Recent analysis from Invesco’s Global Market Strategy Office suggests that we may have already started the transition to the recovery phase of the economic cycle. In environments like this, riskier assets like high yield credit typically outperform their “safer” counterparts. Against this backdrop, the outlook for the asset class looks attractive.

Of course, investing in high yield bonds always comes with risks. If the economic outlook turns out to be more negative than anticipated, we could see credit stress and defaults in the asset class. That said, today is not 2008. Banks and corporates have generally entered this period with strong fundamentals and balance sheets. In other words, the risks this time are not systemic, as they were leading up to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Even if a recession does materialise across global economies, there are some arguments that could work in favour of high yield, such as the lower supply outlook, the improved financial characteristics of high yield companies, and the slightly better credit quality we have seen since the GFC.

With this in mind, we take a closer look at the asset class. We assess its key features, benefits and risks. We also share some case studies and outline how high yield assets behave across a full market cycle.

Finally, for investors who are interested in exploring more innovative areas of the fixed income universe in their search for higher yields, we delve into subordinated debt and hybrid securities. How do they differ from high yield credit, and what can they bring to a portfolio?

High yield credit

From delivering higher income to cushioning volatility, find out what high yield credit can bring to a portfolio.

“What’s in a name?”, William Shakespeare asks us in Romeo and Juliet. “A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet”, he adds. It’s a pretty line in a much-loved play. But it’s a play set in a society where, ultimately, names turn out to be very important indeed.

In the world of asset management, we too love names, classifications and taxonomies. And, in that vein, we begin this piece with a definition. What precisely is high yield credit – and do its financial characteristics live up to the name?

Put simply, high yield bonds are corporate debt securities with a below investment grade credit rating. As the name would suggest, they typically pay higher coupons than investment grade securities. This is to compensate investors for the additional credit risk that they take on when they buy these.

There are several key features that make high yield credit attractive to investors:

We explore these in further detail below.

Historically, high yield corporate bonds have been able to generate high and steady income for investors willing to take on some additional credit risk.

Even in the years between 2008 and 2021, when investors navigated a yield-starved investment landscape, this held true. The average coupon on US high yield during this period was 7.15%. That’s 2.30% higher than US Investment Grade and 4.62% higher than US Treasuries.1

Usefully, the higher coupon payments available on high yield bonds can help cushion price volatility and mitigate downside risks.

To illustrate this point, let’s look back over six crisis events from the last twenty years. In all of them, US high yield bonds exhibited considerably less volatility than US equities.

|

Global Financial Crisis 07/09/2007-12/03/2009 |

European Debt Crisis I 15/04/2010-31/08/2010 |

European Debt Crisis II 21/02/2011-24/11/2011 |

Greek default/Black Monday 10/08/2015-12/02/2016 |

Fear of rising interest rates 23/01/2018-23/03/2018 |

Covid-19 pandemic 10/02/2020-16/03/2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation of US high yield | 11.63 |

5.86 |

6.85 |

7.80 |

4.03 |

20.15 |

Standard deviation of US equities |

45.06 |

28.16 |

29.93 |

24.42 |

25.58 |

86.70 |

Source: Bloomberg as at the dates shown. US High yield is represented by the Bloomberg US HY 2% Issuer Cap TR USD. US equities are represented by the S&P 500 NR USD.

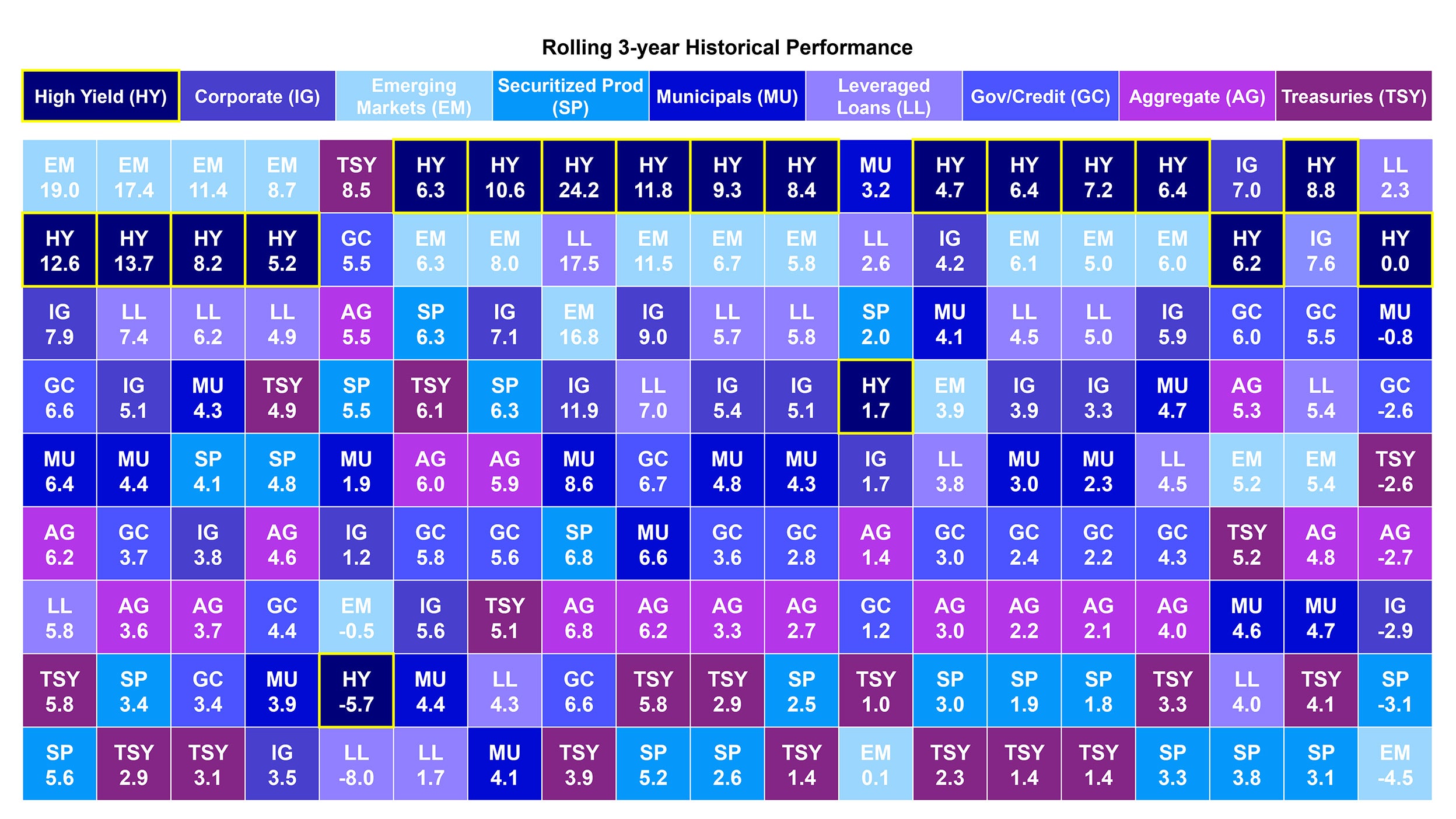

Despite the additional credit risk that investors take on when allocating to high yield over investment grade credit or government debt, the asset class has actually only had four years of negative returns since 2002 (Figure 1). Furthermore, it has consistently outperformed other fixed income asset classes over a rolling three-year period (Figure 2).

Past performance is not a guide to future returns. Source: Bloomberg as of 12/31/2003 – 12/31/2021. US HY is represented by the Bloomberg US High Yield 2% Issuer Capped Index. 2009 Total returns were 58.76%. Past Performance does not predict future returns.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Source: Bloomberg as of 12/31/2004 – 12/31/2022. HY is represented by the Bloomberg US High Yield 2% Issuer Capped Index, Corporate is represented by the Bloomberg US Corporate Index, Aggregate is represented by the Bloomberg US Aggregate Index, EM Hard Currency Agg is represented by the Bloomberg Emerging Market Hard Currency Agg Index, Securitized is represented by the Bloomberg US Aggregate Securitized Index, Treasuries is represented by the Bloomberg US Aggregate Treasury Index, Municipals is represented by the Bloomberg Municipal Index, Govt/Credit is represented by the Bloomberg Government/Credit Index. Leveraged Loans is represented by the Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan index. Past performance does not predict future returns.

High yield bonds can be more volatile in periods of economic stress than their “safer” counterparts, which may act as a deterrent for some investors. However, if you look back through history, you can see that they have also had the ability recover losses quickly (Figure 3).

The below chart tracks the performance of high yield over a twenty-year period, with the blue circles highlighting several key drawdown and recovery periods. There are four case studies in total:

As you can see from the chart, in every one of these instances, the drawdown was followed by a period of strong returns. This is an important feature of bonds. Provided they do not default, they always return to a price of par (or 100) on the redemption date. The pullback to par is a powerful force, particularly if the downturn was driven solely by market sentiment.

Indeed, selloffs are often a result of market sentiment rather than fundamental issues with the company in question. During periods of crisis, high yield bond prices fall as investors rush to buy perceived safer assets like government bonds. As sentiment recovers, investors recognise that high yield assets have been left cheap, and prices recover as they rebuy the bonds they had previously sold.

Source: Bloomberg. As of 12/31/2022. Bloomberg Barclays U.S. High Yield 2% Issuer Cap Index

As with any investment, it’s not all plain sailing. High yield bonds can bring a higher level of risk than their “safer” counterparts. They are more volatile than investment grade credit and government debt and, when markets go into crisis, they will usually see a sharper decline in their price.

The primary risk for this asset class, though, is credit or default risk. This can result in losses due to an issuer’s inability to meet interest payments or to repay the principal sum. Historically, in times of economic stress and uncertainty, the default rate has risen in the high yield market. That said, if we look back through history, it is interesting to note that the market consistently prices in more defaults than actually materialise (Figure 4). This creates opportunities for investors to tap into excess returns.

Furthermore, some defaults present investors with opportunities. Prior to a bond defaulting, there is typically a period where it trades significantly down in price. Investors sometimes choose to invest in these bonds as “distressed” securities, holding them through a period of default and balance sheet restructuring. The rationale is that they can buy these securities cheaply. If the restructure is then successful, the investment may increase in value.

Similarly, defaults do not always result in realised losses for bondholders. If a portfolio manager believes the market value of the debt is lower than the value of the assets backing the bond, they may wish to hold onto that security. If the issuer went into default, the recovery rate on the bond would be higher than the current market price.

Source: Bloomberg, JP Morgan. Using month-end data. Using ICE BAML U.S. High Yield Index (H0A0) for High Yield Spread (OAS). The Forward Loss Rate is calculated by taking the rolling 12-month default rate (by volume) from JP Morgan Research multiplied by 100% less the average historical recovery rate of 40% (from JP Morgan Research). I.e. Default Rate - (100%-40%). The Realized Excess Spread is the HY Spread less the 1-Year Forward Loss Rate. Dates used: Dec 1996 through Jan 2022.

Trying to time markets can be challenging and, for the reasons outlined previously, there is a case for having some high yield exposure in investor portfolios across a wide range of environments. That said, there are some key trends to look out for.

Figure 5 outlines the performance of fixed income assets across a typical market cycle, based on data covering the last fifty years. As you can see, when the economy starts to transition from the contraction phase to the recovery phase, high yield credit leads (followed by equities), outperforming its “safer” counterparts.

Meanwhile, high yield bonds are typically less attractive than higher quality securities during periods of economic slowdown, when government bonds lead in risk-adjusted terms.

Notes: Index return information includes back-tested data. Returns, whether actual or back tested, are no guarantee of future performance. Annualised monthly returns from January 1970 – December 2021, or since asset class inception if a later date. Includes latest available data as of most recent analysis. Asset class excess returns defined as follows: Equities = MSCI ACWI - US T-bills 3-Month, High Yield = Bloomberg Barclays HY - US T-bills 3-Month, Bank loans = Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index – US T-bills 3-Month, Investment Grade = Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate - US T-bills 3-Month, Government bonds = FTSE GBI US Treasury 7-10y - US T-bills 3-Month. For illustrative purposes only. Please see appendices for further information. Sources: Invesco Investment Solutions’ proprietary global business cycle framework and Bloomberg L.P..

In the investment world, the issue of “active” versus “passive” funds has been a subject of ongoing debate for many years. At Invesco, we believe there are no right or wrong answers. There are advantages to both approaches and it ultimately comes down to investor preferences and objectives.

While an active fixed income investor can carry out thorough macroeconomic and credit analysis in an attempt to beat the benchmark, a passive investor can enjoy important cost, liquidity and efficiency benefits.

Furthermore, passive investing isn't just about sitting back and letting the market do the work for you. Passive investors can buy a combination of different ETFs and combine them in a balanced portfolio. As markets change, they can add or remove different exposures to evolve the credit and duration profile of their overall basket of products.

We explore two use cases here, focusing on how investors can use both active and passive vehicles to reduce credit risk.

Thorough credit analysis is an important part of an active manager’s process. The aim is to identify excess return opportunities across a broad range of economic environments, while mitigating against downside risk. This means identifying companies that aren’t reliant on favourable economic conditions to service their debt, and that have strong asset coverage and ample free cash flow, among other factors.

Unlike active funds, ETFs do not differentiate between issuers based on fundamental credit analysis. However, they do allow investors to gain broad market exposure to a particular asset class quickly, cheaply and efficiently.

ETFs also give investors the tools needed to implement an active asset allocation decision based on their own market views and risk appetite. For example, if an investor believes that the market has overreacted to a particular risk factor, with credit spreads widening to attractive levels, they may wish to take on additional credit risk by allocating to a high yield ETF. This would allow them to enhance the income profile of their portfolio.

We share a historical case study to illustrate this further.

The Covid pandemic caused financial market volatility to increase substantially in February-March 2020. As a result, government bonds rallied while credit spreads widened dramatically. However, central banks acted swiftly and aggressively to support the global economy and to stabilise financial markets.

This provided investors with a good opportunity to take on more credit risk, switching from government debt to investment grade credit. For those with a higher risk tolerance, high yield offered good opportunities, including fallen angels and subordinated debt.

For investors looking to make a tactical allocation to high yield, ETFs were an attractive option for several key reasons:

Over the last 10+ years, ESG has gone from a “nice to have” to a “have to have” for many investors. Traditionally, it has been a little harder to implement in the fixed income than the equity space. But, in some respects, corporate bonds have been a good place to start.

One reason for this is that public companies issue equity as well as debt. Unlike bondholders, many shareholders have voting rights. Keen to keep their shareholders on side, this acts as a strong incentive for corporate management teams to drive positive ESG change. Bondholders can work closely with shareholders when engaging with companies on ESG topics.

But what are the benefits for investors? Importantly, ESG investing allows clients to align their portfolios with their values. But, from a financial perspective, there can be benefits too. Many credit events have their roots in some kind of ESG-based deficiency. As such, many investors feel that it is important to incorporate ESG factors as part of the fundamental credit research process.

In the high yield credit space, thorough credit analysis is arguably even more of a value-add than in the investment grade space, as the risk of default is higher.

At Invesco, our fixed income teams assess ESG risk factors based on the same principles as any other risk. They look at:

Our teams have access to third-party ESG data and information providers to help with this process. Furthermore, they use Invesco’s proprietary quantitative ESG risk tool – ESGIntel. These quantitative and qualitative inputs help highlight important ESG risks. However, they are no substitute for the understanding of an issuer that comes from our experienced credit analysts.

Rising stars and fallen angels

Catch a falling star: how can investors capitalise on credit downgrades?

There is a well-known Latin phrase, “per aspera ad astra”, which translates to “through adversity to the stars”. Some fixed income securities experience this upward trajectory, while others see their fortunes decline. We call these rising stars and fallen angels.

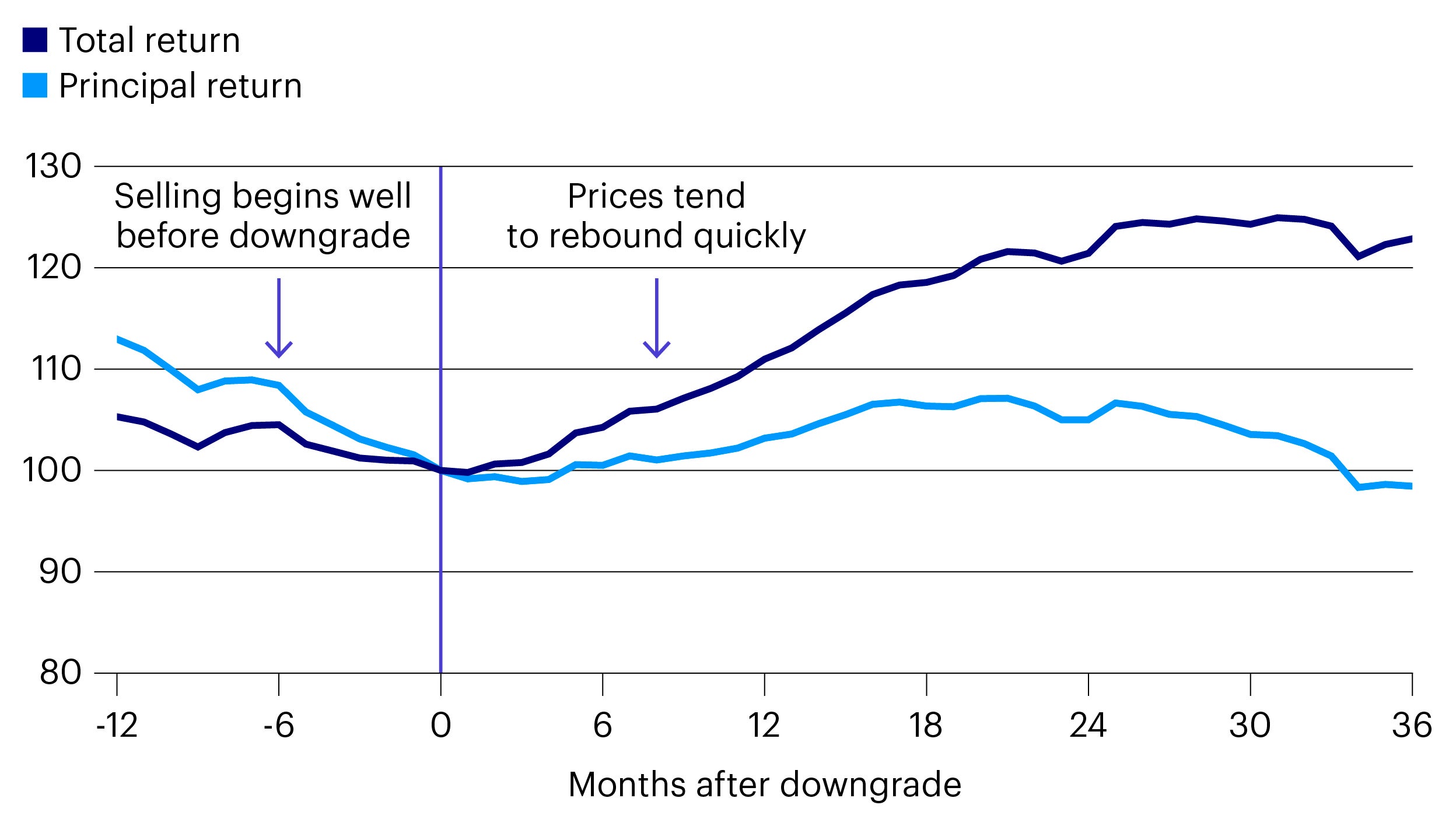

In the period surrounding a downgrade, a bond’s price will usually fall more than it should, as illustrated by Figure 6. One reason for this is that investment grade products are forced to sell the bond. This combination of value, yield pick-up and recovery potential can make fallen angels appealing, particularly if you believe the economy or industry in question will recover.

For illustrative purposes only. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

2020 was a record year for fallen angels after a perfect storm of collapsing energy prices and Covid lockdowns. This led to an improvement in the overall quality of the high yield market. After economies reopened, 2022 saw a total $110 billion worth of debt upgraded to investment grade – also the highest on record.2

High yield fallen angels typically underperform other types of credit during economic downturns and recessionary periods. However, they subsequently tend to recover much faster, outperforming both broad investment grade and high yield credit.

Meanwhile, they tend to perform best during the middle of the cycle when there is strong economic and credit growth, a flattening yield curve and a lower risk of default.

Innovative income: subordinated debt and hybrids

Can subordinated debt deliver superior returns?

In recent years, investors have increasingly sought out more innovative sections of the fixed income market in their search for yield and diversification.

For those looking to increase their income without taking on more credit risk, some subordinated debt and hybrid securities have proved attractive. We introduce three of these – Additional Tier 1 Capital Bonds (AT1s), corporate hybrids and preferred shares.

AT1s are securities issued by European financial institutions. They are relatively young financial securities, first introduced after the GFC. They were designed to prevent contagion in the financial sector by acting as a readily available source of bank capital in times of crisis.

AT1s have several key features that make them attractive to yield-seeking investors:

In some ways, corporate hybrid bonds are similar to AT1s. However, instead of being issued by banks, they are issued by companies in sectors like energy, utilities, telecoms and pharmaceuticals. They are often issued by investment grade companies as a more flexible way to borrow and support their credit ratings, as agencies consider hybrids to be part debt, part equity.

Just like AT1s, corporate hybrids are senior only to common equity. This subordination factor is what drives their high yield. Issuers have a significant deterrent (via coupon step-up) to encourage them to call the bond on the first call date, generally after five years, which accounts for their low duration.

When determining whether hybrids offer value relative to more senior debt, it’s the spread that they offer over IG credit that is important.

Preferred shares are hybrid securities that combine characteristics of bonds and equities. For example, as well has having scheduled interest payments, defined par amounts and credit ratings, they are also perpetual (or long dated) in nature and are subordinated within the capital structure.

In the US, some banks issue preferred shares to fulfil similar capital funding requirements as European banks do with AT1s. Preferred shares are typically issued by investment-grade issuers. Their high yields are driven by their subordination – not the riskiness of the issuer. They are issued either with fixed or variable rates.

In higher yielding asset classes, the risk of defaults, losses and impairments is greater than when investing in “safer” securities like government bonds and IG credit. Against this backdrop, a team of skilled credit analysts can add considerable value by actively researching companies to differentiate between the winners and the losers.

At Invesco, we have over 200 fixed income specialists – many of whom are seasoned credit researchers. When analysing issuers for inclusion in client portfolios, they bring decades of experience across companies, markets and economies.

Meanwhile, for investors who prefer a passive approach, Invesco is at the cutting edge of ETF development, offering a broad range of exposures.

Want to learn more about the fixed income capabilities that are available in your region, including our high yield offering? Click the links below to be redirected to your local Invesco website.

1 Source: Invesco and Bloomberg as at the dates shown. Data based on the Bloomberg US High Yield 2% Issuer Cap Index.

2 Source: JP Morgan (Default Monitor, 3 January 2022).

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

All data is provided as at the dates shown, sourced from Invesco unless otherwise stated.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.