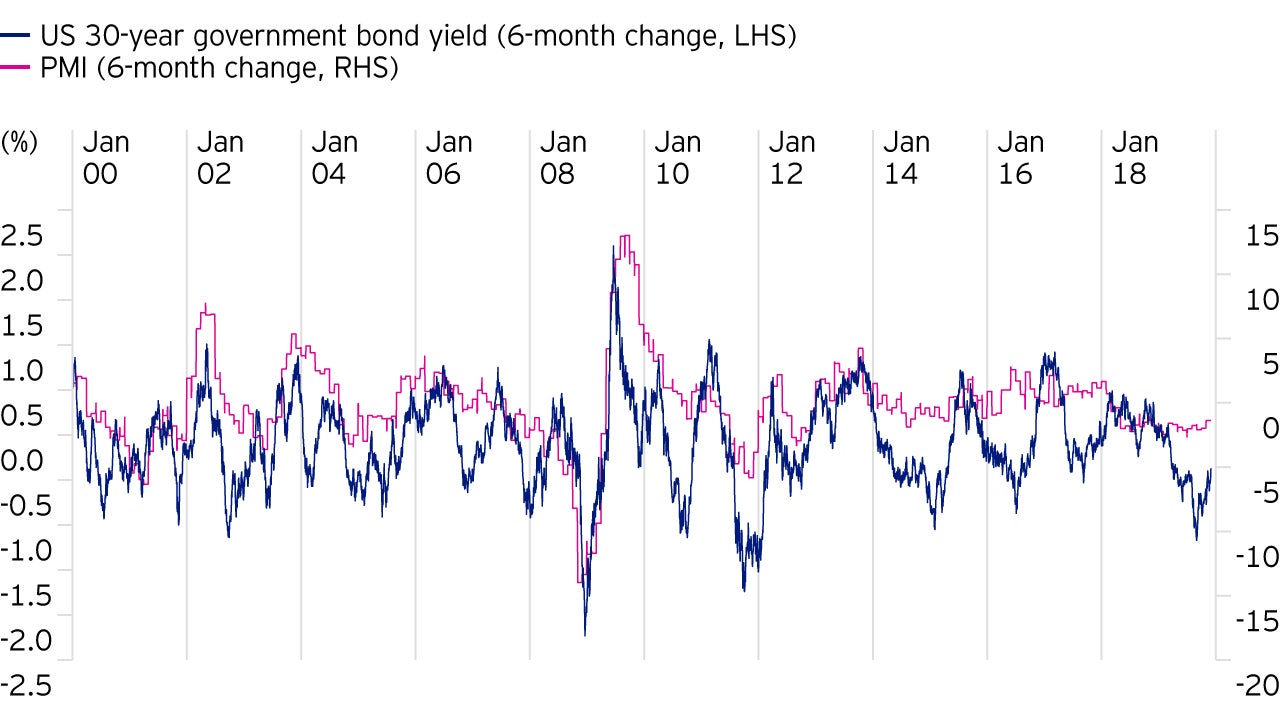

During the summer, we believe bond yields over-reacted to weakening economies and perceived trade issues – the US 30-year Treasury yield briefly reached 1.90% on 28th August, a big move from 3.45% in the final quarter of 2018, according to Bloomberg.

There are three ways the relationship in the left-hand chart above can come back into line - rising bond yields, weaker PMIs or nothing much happening for six months. Since the summer, bond yields have risen a small amount (the US 30-year treasury yield is currently 2.2%, as at 11th December 2019) and PMIs have been subdued (at just below 50).

A further rise in yields to 2.6% would bring the market back into alignment with the PMIs and, in the process, give us close to a 50% retracement of the rally over the last year – not unusual even in an ongoing bull market.

So, even if you have a bearish view of the global economy, you might not want to own too much outright bond duration – at least for a few more months.

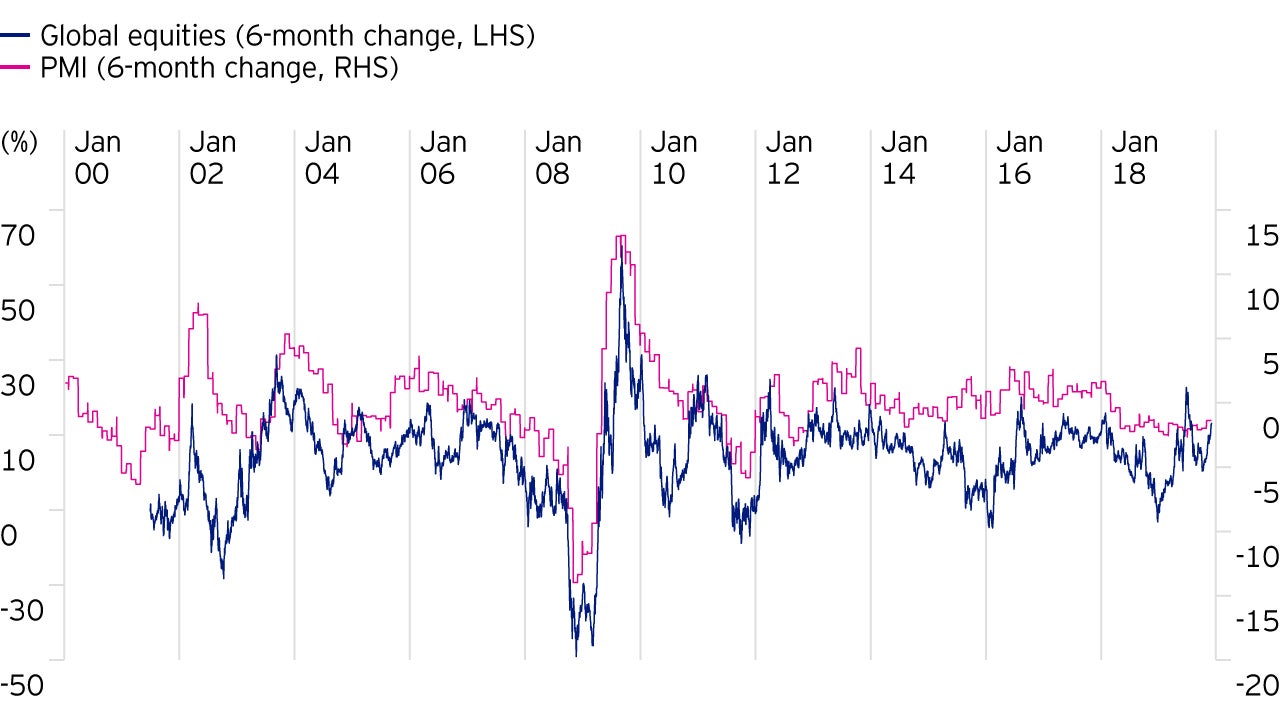

At the same time, the implications of a continued sell-off in bonds should also hint at caution on equities. If the future earnings stream of equities improves with a strong economy, the value of those earnings can also increase if bond yields fall. This latter driver explains why 2019 equity performance is running ahead of the PMIs.

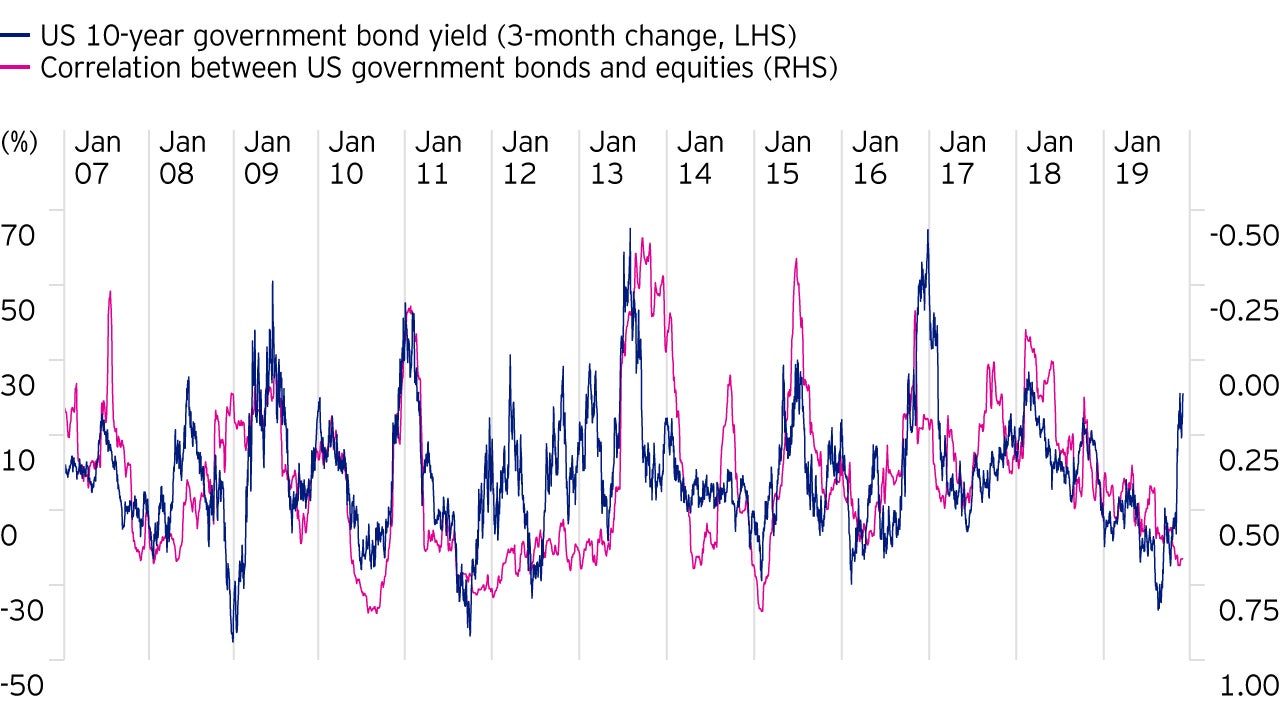

However, as the chart below shows, a move higher in yields can also shift the normal diversifying relationship between bonds and equities to one where they can both lose money at the same time.