Taking stock of the green rush

Investors are focusing too much on certain sustainability areas, without paying attention to the broader - or even counterproductive - effects. Invesco partnered with The Economist to explore the topic in more depth in their ‘The art of the possible’ series.

Sustainability is the new investment ‘must-have’. It’s estimated that about 20% of investments are badged environmental, social and governance (ESG) of one form or another, and that proportion grows continually. That’s a lot of money: about $20trn.1

This has generated a ‘green rush’—what’s now the largest trend in investment. But it isn’t a silver bullet to make money and do good. Although the positive aspects are very real, there are also challenges: how the benefits and costs of such investments are apportioned—indeed, even down to how they are calculated.

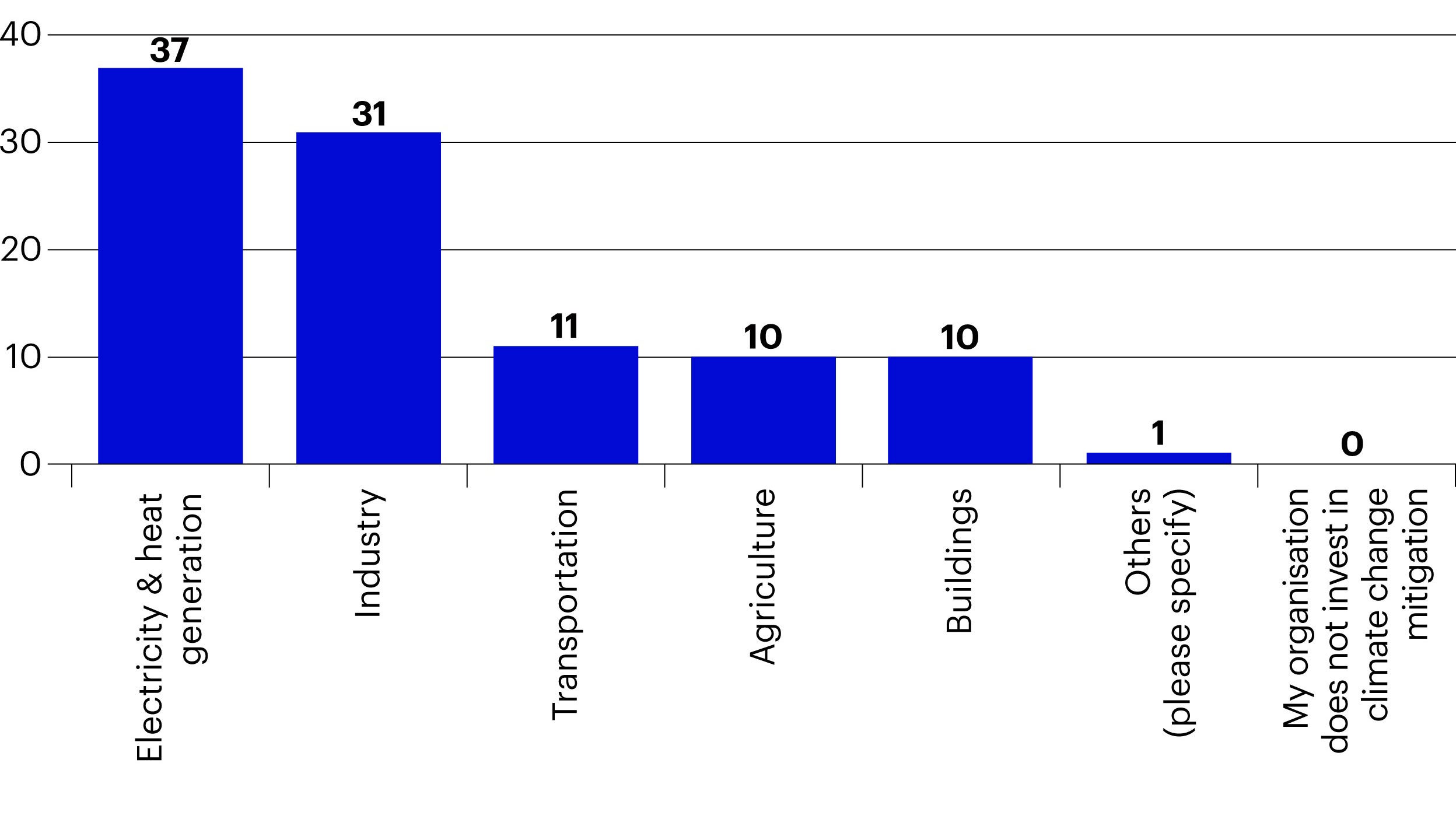

There is, for instance, a persistent disparity between where environmental investments are going—largely towards established technologies such as wind and solar—and integral parts of the sustainability puzzle that remain underinvested. A recent survey of large investors globally conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit found that electricity and heat generation, followed by industry-related investments, represent the lion’s share of sustainable investments. Jason Tu, cofounder and CEO of ESG analytics company MioTech, is seeing a lot of investor interest in “energy generation, transmission or storage, or usage such as electric vehicles”. He also cites farming technology as a particularly hot topic among investors.

Conversely, buildings, transport and agriculture, despite being major sources of greenhouse gases (GHG), have relatively low uptake.2

How useful is ESG?

“The starting point for ESG is flawed,” argues Aswath Damodaran, professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business. “We're trying to substitute company behaviour for laws we should be passing as a society.”

However, others object that pushing this back onto society or the individual is a distraction from the role large corporations play—and sometimes an intentional distraction at that.

“Professor Damodaran is quite wrong to think that anyone in ESG actually thinks voluntary action is a good substitute for good laws,” says Mark Campanale, founder and executive chairman of the Carbon Tracker Initiative. “Quite the opposite. What ESG does however recognise is that the law is a minimum and we should all aspire to higher standards. When governments abrogate their responsibilities—for example by allowing themselves to be lobbied by powerful business interests to block certain standards—then shareholders can step in and take action.” He points to the recent removal of senior executives at Rio Tinto over the mining violation of indigenous Australians’ historical sites as a good example of this.

Mark Campanale, Founder and executive chairman of the Carbon Tracker InitiativeWhat ESG does recognise is that the law is a minimum and we should all aspire to higher standards. When governments abrogate their responsibilities—for example by allowing themselves to be lobbied by powerful business interests to block certain standards—then shareholders can step in and take action.

Technology is playing an increasing role in exposing these sorts of abuses. Mr Tu cites the use of satellite imagery “to see whether there's any decrease in greeneries at the plantation, or any kind of signs of pollutants around a 30 km radius of a factory”.

This helps investors ensure that their sustainable projects are actually doing good—and choosing projects where they care about their success is exactly how Professor Damodaran suggests approaching green investing. “My advice to investors is pick your dimension of goodness,” he says. “Each of us has something we think is most critical to us, and consider investing based on that dimension, which means ESG scores are completely useless.”

Aswath Damodaran, Professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of BusinessMy advice to investors is pick your dimension of goodness. Each of us has something we think is most critical to us, and invest based on that dimension, which means ESG scores are completely useless.

How well does a company perform on gender diversity, water usage, emissions and so on? Distilling all these factors and more to one ESG number is obviously problematic.3 Some investors want as low fossil fuel exposure as possible—while others will intentionally be targeting more carbon-intensive companies—to finance a transition from the brown to green economy. ESG scores cannot resolve this; it’s only the starting point.

Mr Campanale takes a different approach: “ESG scoring is neither an investment thesis nor a strategy. What’s more compelling is to find areas that can demonstrate a valuable impact on society, for example investing in the clean energy revolution, or medical technologies. ESG-led investment research strategies that allow you to invest in a spread of high social impact enterprises is really at the heart of responsible finance.”

Pedal to the metal

Such strategies can’t be summed up in one number. A single ESG score—one number encompassing diverse factors—arguably doesn’t tell you much. A fund or stock can have a high ESG score by being in an industry with a low carbon footprint, such as finance, for example, or simply by reporting on lots of metrics that ESG ratings agencies score on. Some large oil companies, for example, score well on transparency, compensating low E with high G.

A positive impact in one area, earning a good ESG score, can also have a negative impact in other areas, which may not be highlighted by some ESG metrics, and so asset owners may be unaware of important consequences of some of their investments. One example of this is the knock-on effect of low-carbon technologies on metal extraction. These technologies use much larger amounts of metal than fossil fuel-based systems, creating an exponentially rising demand. An electric car typically contains 80 kg of copper, four times as much as a petrol-fuelled one. Both wind and solar power plants contain more copper than their fossil fuel equivalents: a typical solar plant contains about 5 kg of copper per kilowatt versus 2 kg per kilowatt for a coal-fired power station, points out economist Frances Coppola.4

Materials management activities, including copper mining, is related to more than half of all GHG emissions, according to the OECD’s Global Resources Outlook to 2060. The report estimates that extracted resources will increase from 79 to 167 gigatonnes (Gt) by 2060, based on an assumed growth rate of 2.8%—causing a rise in emissions to around 50 Gt CO2 equivalents.5

In addition, much of this mining takes place in emerging markets and is linked with local environment and water depletion as well as often abusive labour practices. Within and between societies, there will therefore be winners and losers in this ‘green rush’. If left unchecked, there’s a real danger that the losers will be those who have all too often been in that position historically—those at the bottom of the income scale in emerging markets.

There will be winners and losers in this ‘green rush’. If left unchecked, there’s a real danger that the losers will be those who have all too often been in that position historically—those at the bottom of the income scale in emerging markets.

“It's surface level ESG, because you think about carbon footprint, you think people who produce gas cars create this huge carbon footprint,” says Professor Damodaran. “If you create electric cars, you're good. But electric cars create their own costs. And if you start digging into those costs, the question you have to ask is, are we really trading one devil for another?”

Given the reliance of the green energy transition on poorly regulated mining in these regions, does this not risk minimising the S in ESG? And is this not creating wilful blind spots to other forms of environmental degradation? It leads to the accusation, expressed pointedly by charity War on Want, that this green rush threatens a “new form of green colonialism that will continue to sacrifice the people of the global south to maintain our broken economic model”.6

For Professor Damodaran, addressing the issue cannot rest at the door of the corporation: “Much of the ESG literature starts with an almost perfunctory dismissal of [founder of monetarism] Milton Friedman’s thesis that companies should focus on delivering profits and value to their shareholders, rather than play the role of social policymakers,” he says.

Related articles

Footnotes

-

1 Source: US$17.5trn out of the US$79trn of total estimate from Boston Consulting Group and the US SIF Foundation, cited in the Financial Times, February 26th 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/e969217c-f001-11e9-a55a-30afa498db1b?segmentId=47561bcd-230d-6768-b4a1-deb6edc93a7b

2 Source: https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/eiu_efund_tech_imperative_1202.pdf

3 Source: For a basic overview example of ESG ratings and how they work, see: https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings

4 Source: https://www.coppolacomment.com/2021/03/from-carbon-to-metals-renewable-energy.html

5 Source: https://www.oecd.org/environment/waste/highlights-global-material-resources-outlook-to-2060.pdf

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

-

This article is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.

Produced by € BrandConnect, a commercial division of The Economist Group, which operates separately from the editorial staffs of The Economist and The Economist Intelligence Unit. Neither € BrandConnect nor its affiliates accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any party on this content.