Equities Trailblazer China

China is likely to emerge as a dominant growth engine of the world over the next decade.

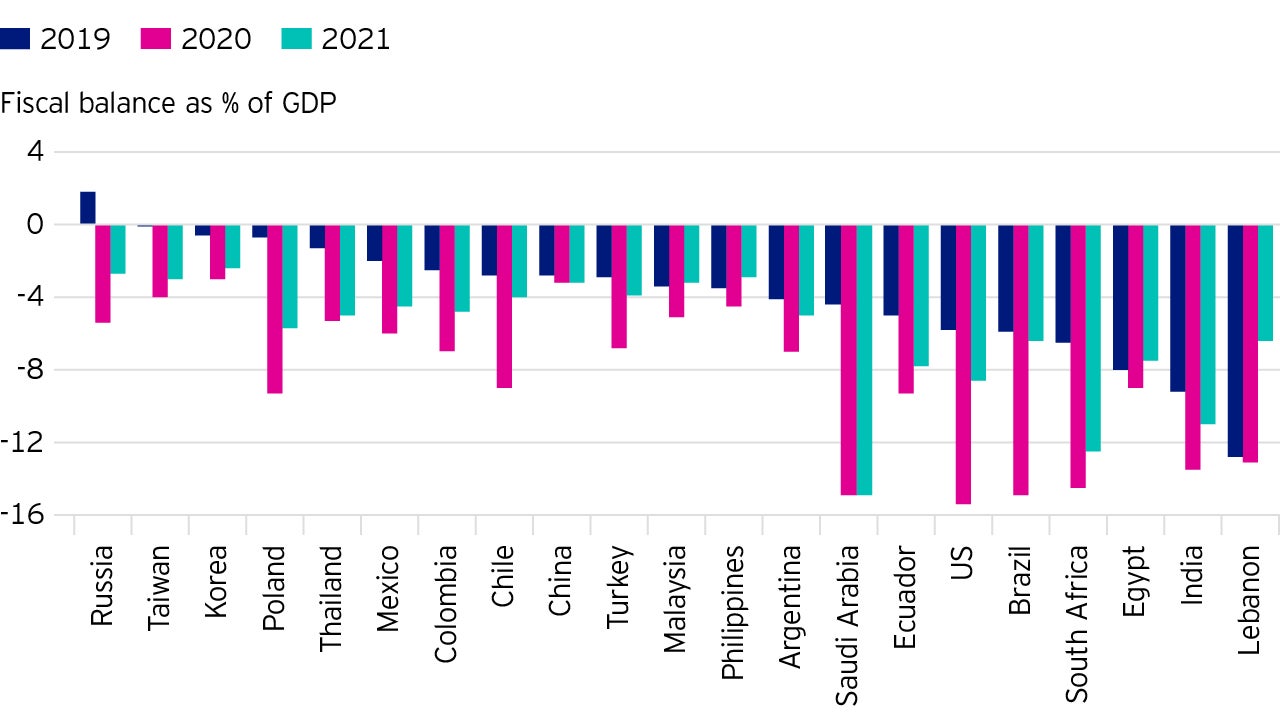

The pandemic crisis has put government finances under severe pressure, although we do need to differentiate between countries with structural imbalances and those who are better positioned to cope with a collapse in GDP.

It appears that fiscal balances have been greatly disturbed by both the necessary efforts to deal with the pandemic crisis and the proximate collapse in growth and employment all across the world.

However, it is structural imbalances that we are most concerned with, not the unforeseen pandemic cyclical shock.

And here we can begin to separate the economies that we believe can successfully manage the crisis from those that may experience more prolonged damage from it.

In our opinion, the strong here are extremely obvious and almost entirely in Asia: Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

We believe that China, of course, is in that group, as well.

Its fiscal capacity appears to be durable, given enormous public ownership of large swaths of industrial, financial and physical assets.

We do recognise, however, that its cyclical “augmented” fiscal deficits are large and growing.

Finally, though perhaps less intuitively, we also believe that Russia is a bastion of fiscal strength.

Over the past decade, the country has, in our view, built a fortress-like economy, that can prove to be resilient to even the most damaging downturn in energy prices.

Frankly, we are very concerned with unsustainable debt dynamics in South Africa and Brazil, in particular, among the larger economies.

We also have a concern about unsustainable deficits in India and Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia, in our view, is far frailer than most investors acknowledge.

A structural fiscal deficit there is coupled with utter inflexibility of social spending (the social contract between the big royal family and the broader population).

Finally, we believe the economic circumstances in Mexico could prove to be problematic.

While the ratio of the country’s fiscal debt to its gross domestic product (GDP) may not appear to be an issue superficially, its fiscal capacity is rather limited.

It is additionally worth underscoring that we think the most difficult fiscal dynamics in the developing world are disproportionately concentrated in the frontier market geographies, where fiscal capacities are extremely under-developed.

These include countries like Argentina, Ecuador, and Lebanon that have been highly dependent on assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF); countries that some view as IMF success stories, like Egypt (still an EM country by definition); and those that may be dependent on IMF support in the future, like Pakistan.

Given these uncertainties, we believe the frontier markets present considerable risk for investors.

We think growth in frontier markets and some EM countries is plagued by some of the most difficult fiscal dynamics.

We are particularly concerned about the unsustainable fiscal debt circumstances among four larger emerging markets - Egypt, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa.

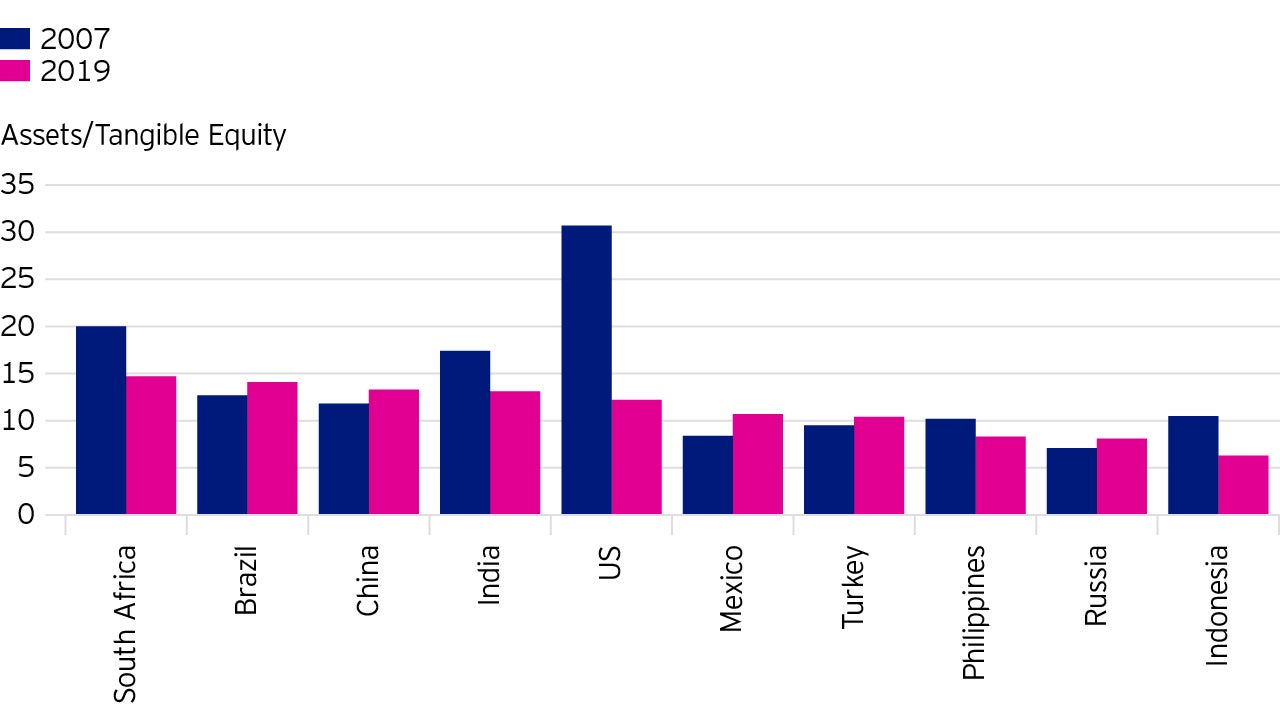

Broadly speaking, regulatory capital levels are strong across the EM universe.

After many years of disappointing economic growth and credit expansion, there are, in our view, few outsized structural problems among EM banks.

However, we believe cyclical stress will likely have a severely negative impact on EM bank earnings in 2020 and will likely test their resilience.

We believe the countries with strong banking systems are easy to identify - Russia, Peru, Indonesia, the Philippines, and perhaps, unexpectedly, Egypt.

These countries have banking systems with low leverage, extremely demanding capital regimes, and what we consider to be strong funding and excellent liquidity.

The risky three in our view are Turkey, India and South Africa.

We think, among the big EM economies, Turkey and India are the standout structural risks.

The Turkish banking sector is a volatile mix of external funding risks, growing asset quality stress and what we consider to be self-sabotaging macroeconomic policy decisions.

India suffers from a long-burning hangover of asset quality problems, including a corporate credit cycle among the public sector banks that has persisted since 2015, as well as a liquidity crisis in the non-bank financial sectors that has prevailed since 2018.

This cyclical impairment stress could prove to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back, as the private banks - the last bastion of India’s financial sector - could suffer severe consequences if the volume of NPLs greatly increases as a result of this extended lockdown.

All of this has the potential to lead to much weaker structural economic growth, especially if the challenges of this period are not managed properly.

South Africa is also problematic, in our view, because of its uniquely challenging macroeconomic conditions (including external imbalances, unsustainable fiscal dynamics and structurally impaired growth), which could cause deep cyclical stress to bank profitability and capital.

Among the big EM economies, Indonesia, Russia, the Philippines and Peru have the lowest bank assets/tangible equity ratios.

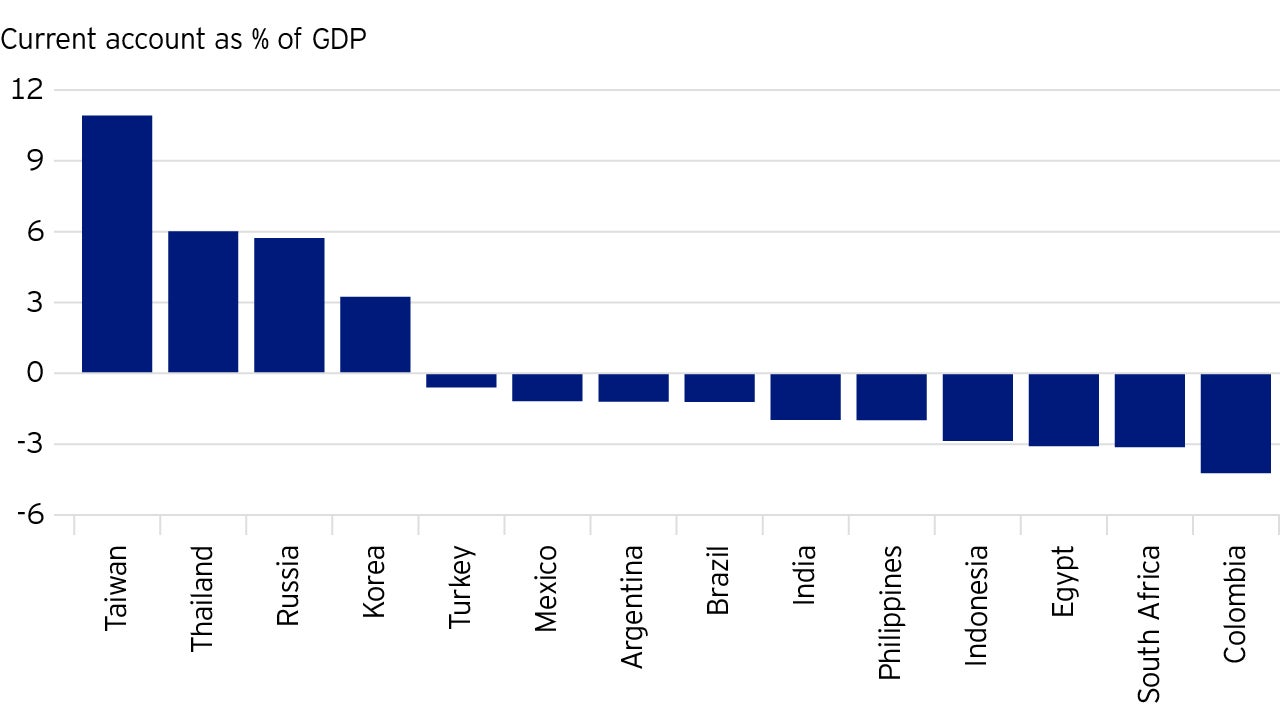

External imbalances are generally the bane of developing countries as they do not have the same luxuries as the developed world.

In general, developing countries’ fiscal and monetary policies can be severely hindered by external constraints.

Unlike the US, which can practice the demand management described by economist John Maynard Keynes - whereby a government can support demand by fostering full employment equilibrium in the economy - nearly all emerging countries have a more limited ability to employ this strategy when a recession might require it.

Given the external constraints, developing countries should be extremely cautious about running serial current account deficits.

If they do so, we believe their currencies could decline, inflation in their country could rise, and real economic growth could be greatly diminished.

At first blush, one can generalise that the manufacturing powerhouses of Asia have demonstrated greater resilience in this worldwide economic crisis, as they have maintained their current account surpluses.

Taiwan and South Korea, in particular, have demonstrated solid performance on this measure.

But perhaps the real rock has been Russia, where despite the carnage of a sudden collapse in crude and natural gas prices, we believe the country will run a modest current account surplus of 1.5% in 2020.1

Among the larger EM countries, Taiwan, Thailand, Russia and South Korea had solid current account surplus in 2019.

We do not live in “normal” times, and nuance really matters across EM today.

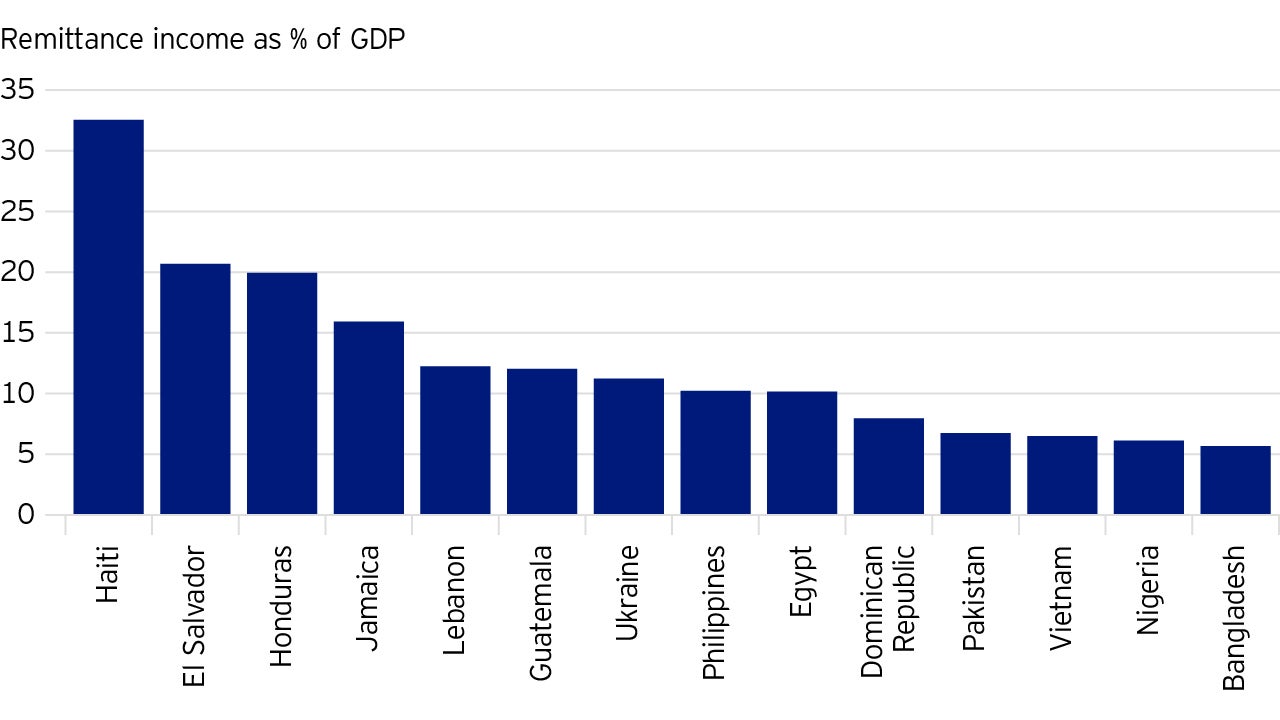

While the dramatic decline in oil prices and domestic recession may help alleviate balance-of-payment pressures across many developing countries, we believe these developments will be offset by a dramatic retreat in remittance income (money sent by foreign workers to their home country) and tourism in many economies, including:

The big frontier economies have the highest risk, given how much remittances contribute to their GDP.

Remittances are money sent from foreign workers to their home country.

The developing world exhibits great heterogeneity in terms of sovereign risk (the possibility that a country will default on its sovereign debt), between net external creditors and debtors in terms of external balances.

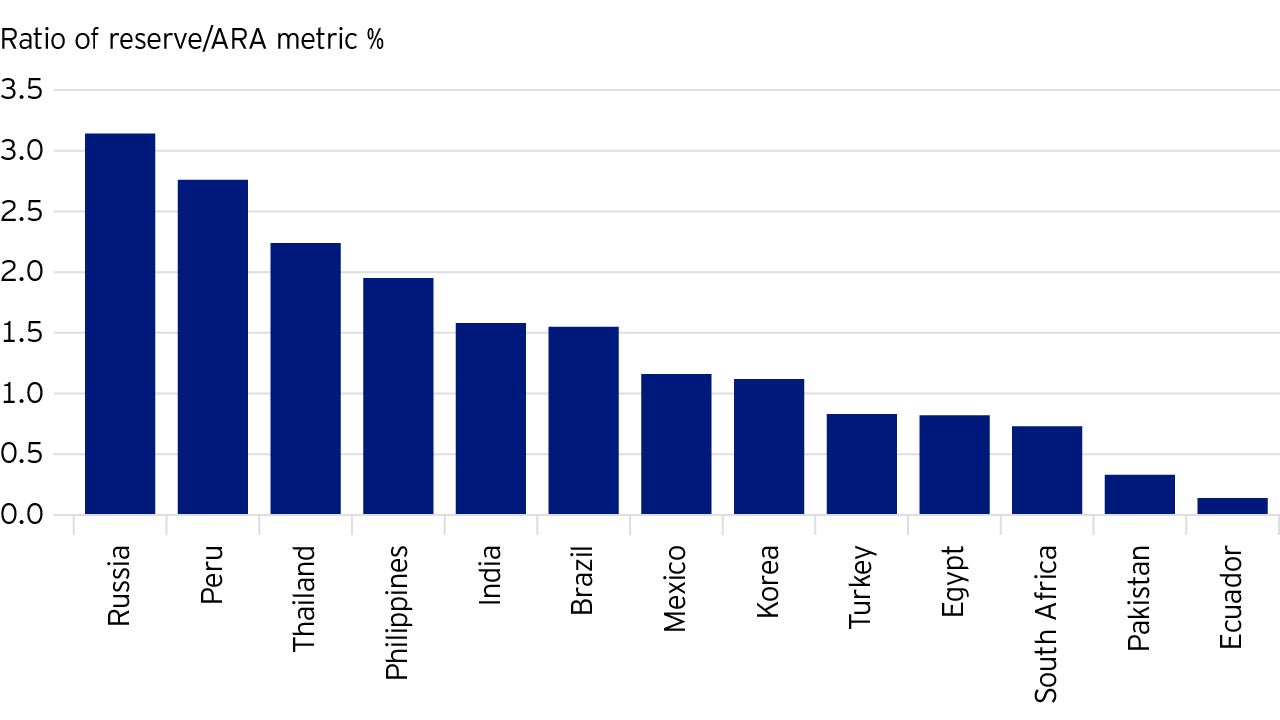

Among the countries with the circumstances to manage sovereign risk are Taiwan, South Korea, Peru and Russia.

There are also notable strengths in Southeast Asia - namely Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam.

India, Brazil and Mexico also are braced by reasonably healthy external debt circumstances.

We believe the weaker countries with regard to sovereign risk are just as easy to identify.

They are, in our view, Turkey and South Africa among the larger economies, and Egypt and Pakistan among the less developed economies.

The countries that we believe present the greatest sovereign risks are concentrated, again, most prominently in the frontier markets - Argentina, Ecuador and much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Russia, Peru, Taiwan and South Korea have the strongest sovereign circumstance globally in terms of reserve adequacy.

Which economies are likely to hit the wall in response to the pandemic?

To find out more, read the next article.