The output gap revisited

John Greenwood. Chief Economist, Invesco Ltd and Adam Burton. Assistant Economist.

Following a decade of sub-target inflation in most developed economies, the monetary and fiscal responses to the Covid-19 pandemic recession have renewed the inflation debate.

Broadly speaking, there are two theories of inflation.

The first theory focuses on the quantity of money, relying on the concept that real money balances are generally stable relative to income, which implies that excessive increases in the quantity of money tend to lead to increased nominal spending and ultimately inflation.

The second theory focuses on “economic slack” or the output gap, proposing that differences in “aggregate demand” and “aggregate supply” are the main drivers of inflation.

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic recession and the monetary and fiscal responses, the US broad money growth rate has reached historic highs of 23% year-on-year in July, whilst “economic slack” as measured by the US unemployment rate has risen sharply.

Therefore, current economic and monetary conditions provide a perfect petri dish to test both theories.

In this piece, we critique the output gap theory of inflation.

Empirical analysis

Before we consider the output gap theory of inflation theoretically (and mechanically), the first port of call is to analyse the empirical data to see if what is predicted by the theory is observed in reality.

Economic slack is a nebulous term, but most adherents of the output gap theory of inflation generally associate it with slack in the labour market.

Defining unemployment and the labour force is beset with numerous problems (especially how to count individuals who are marginally attached to the labour force), but for brevity’s sake in this survey we will consider only the U3 and U6 unemployment rate.

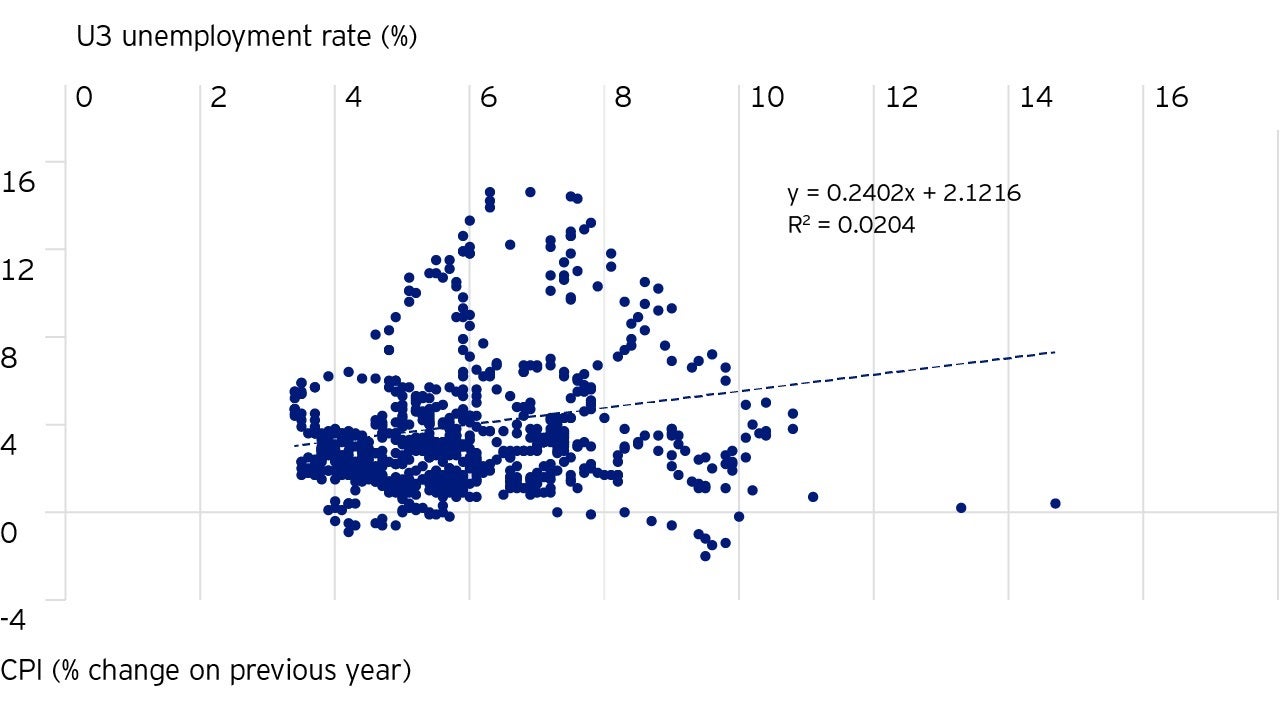

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the narrowly defined U3 unemployment rate (%) and the headline CPI inflation rate (% change on previous year) for the period 1955 to 2020.

At first glance, it is difficult to discern a relationship between unemployment and inflation.

Between 1955 and 2020 (the period of time for which the data for both U3 unemployment and CPI inflation are available), the correlation between the two is effectively zero, with a positive coefficient of regression of 0.24, implying that lower levels of U3 unemployment are associated with lower rates of CPI inflation - the exact reverse of what the theory predicts.

U6 underemployment (which was first recorded in 1994) too has an almost negligible correlation with CPI inflation.

Another empirical problem with the output gap theory of inflation is a measurement problem, as the various organisations that track output gaps for individual economies have different methodologies leading to contrasting values of the output gap.

For example, the IMF, the OECD, the European Commission and the IIF (Institute of International Finance) all track output gaps for major economies, and often have different values for output gaps.

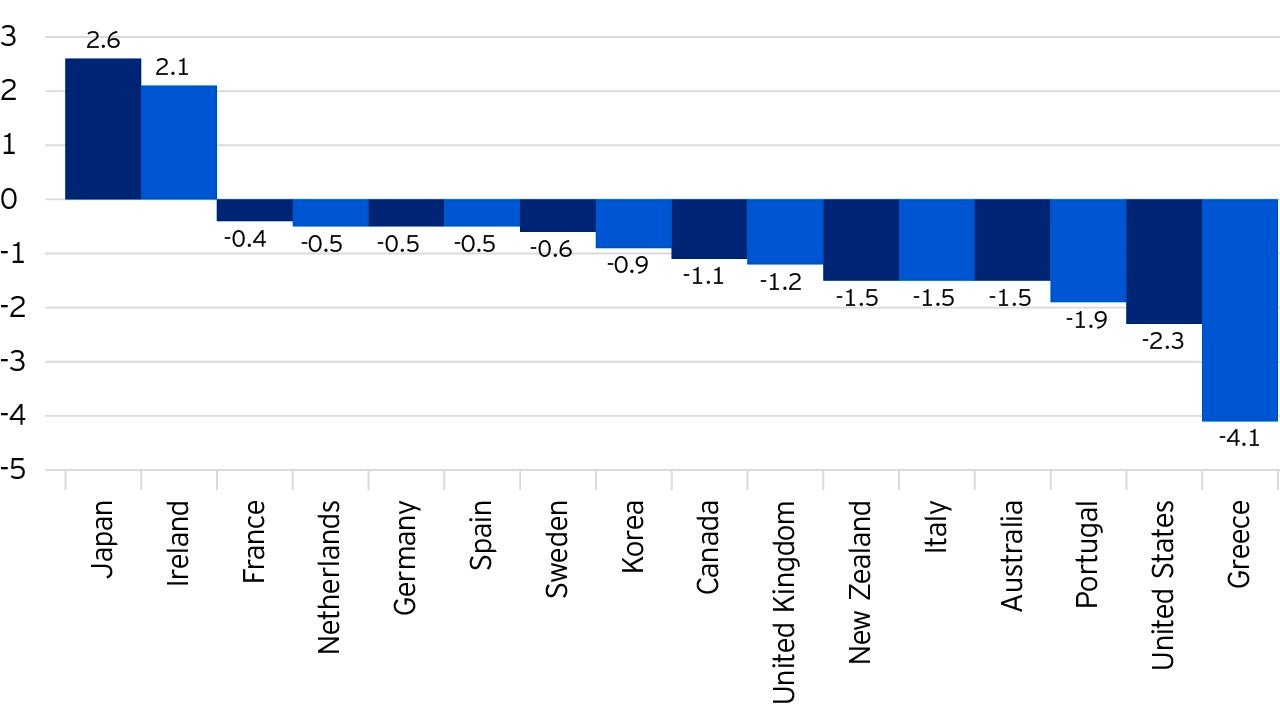

Figure 2 highlights the difference between the IMF and OECD values of output gaps for major economies, as a percentage of GDP.

These differences range from -4.1% of GDP in Greece to +2.6% of GDP in Japan, highlighting the difficulty in even measuring the output gap, let alone using the output gap to predict inflation.

Theoretical critique

In terms of the transmission mechanism, the output gap theory of inflation stipulates that low unemployment leads to rises in wage inflation as firms have to offer higher remuneration to secure enough talented workers, and this increase in costs will lead to more general price inflation.

The fundamental problem with this theory is that wages are a transfer of cash from firms to employees, so if wages are rising there will be less cash available to firms to purchase goods and services therefore on aggregate purchasing power has not increased - there has only been a transfer of purchasing power from firms to employees.

On both empirical and theoretical grounds, therefore, the output gap theory of inflation suffers from serious shortcomings and should not be relied upon for making predictions.

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

-

Where John Greenwood and Adam Burton have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.