Investing in Brazil amid the coronavirus crisis

Justin Leverenz. CIO Developing Markets Equities and Senior Portfolio Manager, Invesco New York.

The widely touted view - amplified for a few years after the 2007-2008 global financial crisis - was that the developing world would be the dominant global growth engine, with larger emerging market (EM) economies converging toward G-7 income and productivity levels.

While we are critical of this view as heuristically naïve, we believe that superior economic growth is not a necessary premise for unearthing compelling investment opportunities in and around the developing economies.

In our view, Brazil is clearly one of those economies that offers what we consider to be inferior structural macroeconomic growth, but it still has some potentially spectacular investment opportunities.

You may also be interested in listening to our recent webinar with Justin: Current Black Swan Event Impact and Potential Opportunities in Emerging Markets

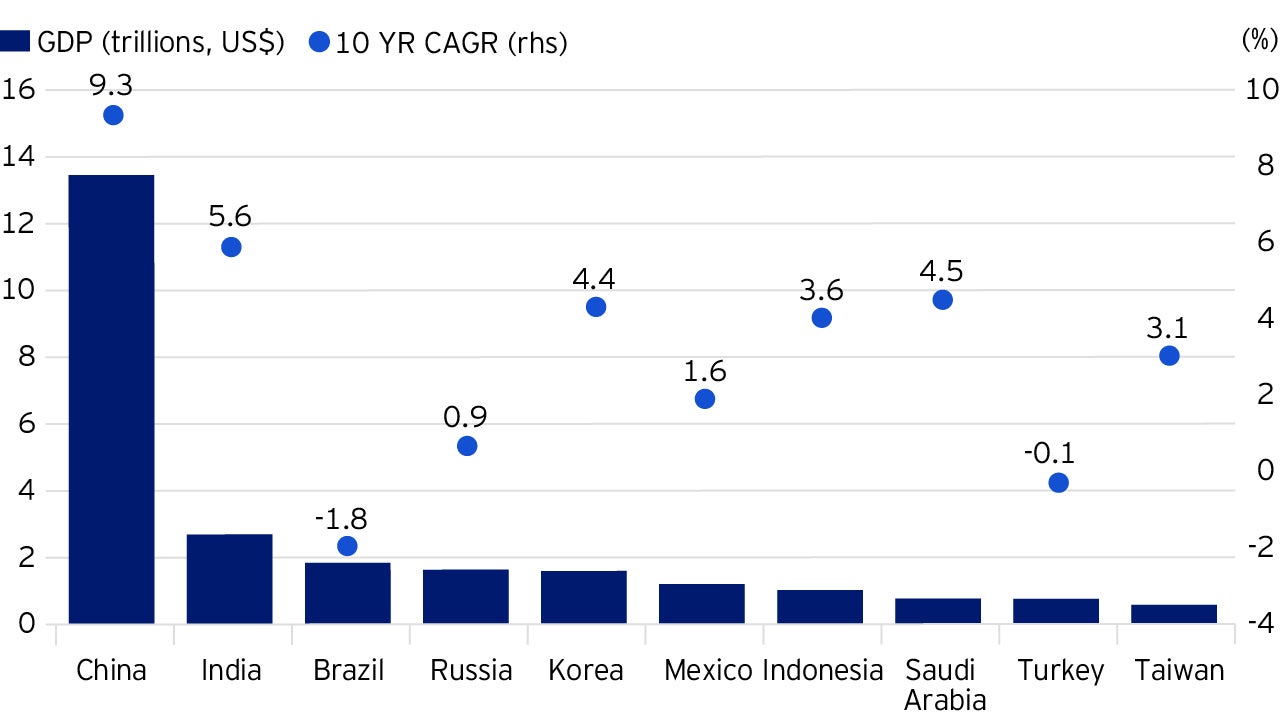

Despite Brazil’s being the third-largest EM economy, its growth in the past decade was meagre.

On a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) basis, it retreated by close to 2%.

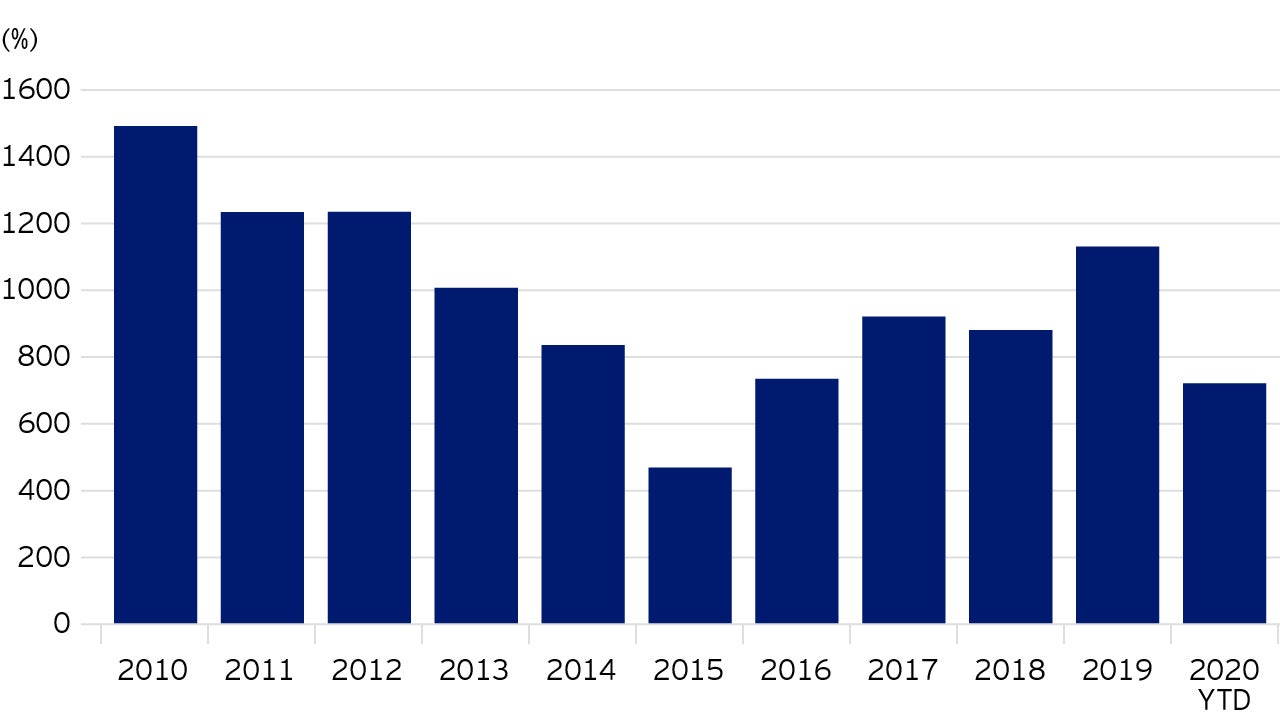

As for its capital market, the Brazilian stock exchange’s total market capitalisation has yet to rebound to the historical peak of the US$1.5 trillion it achieved in 20101.

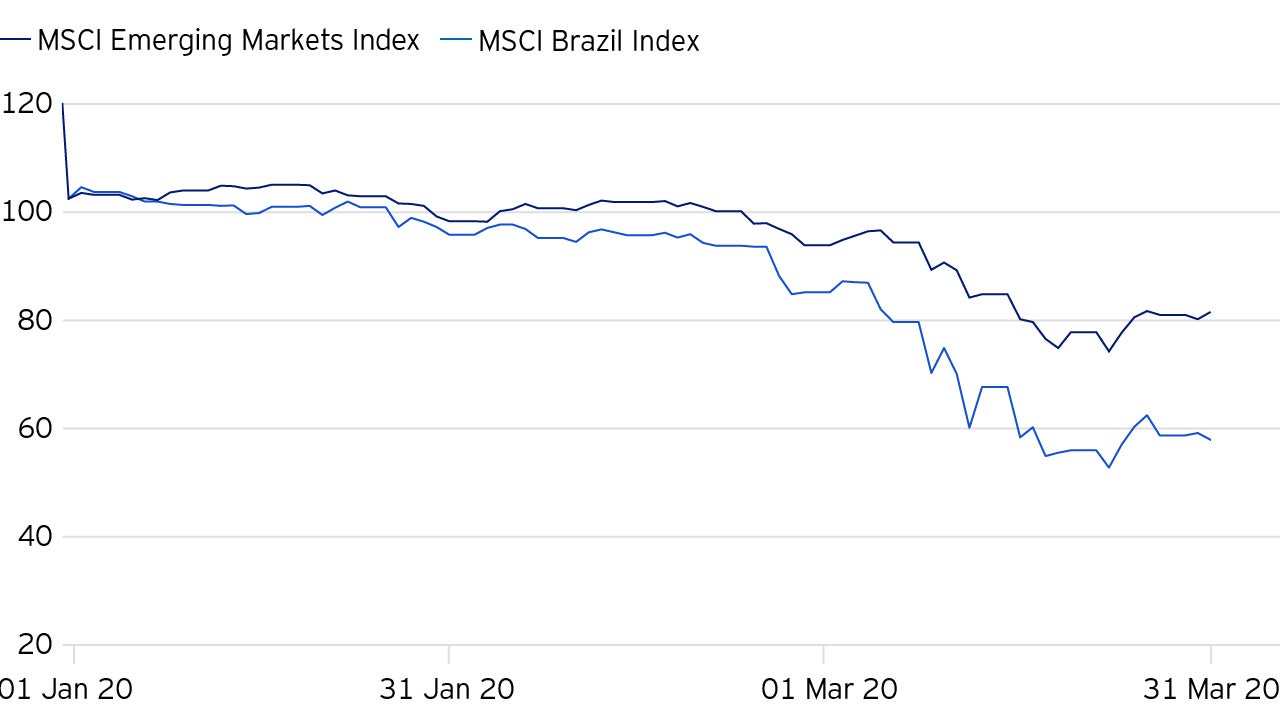

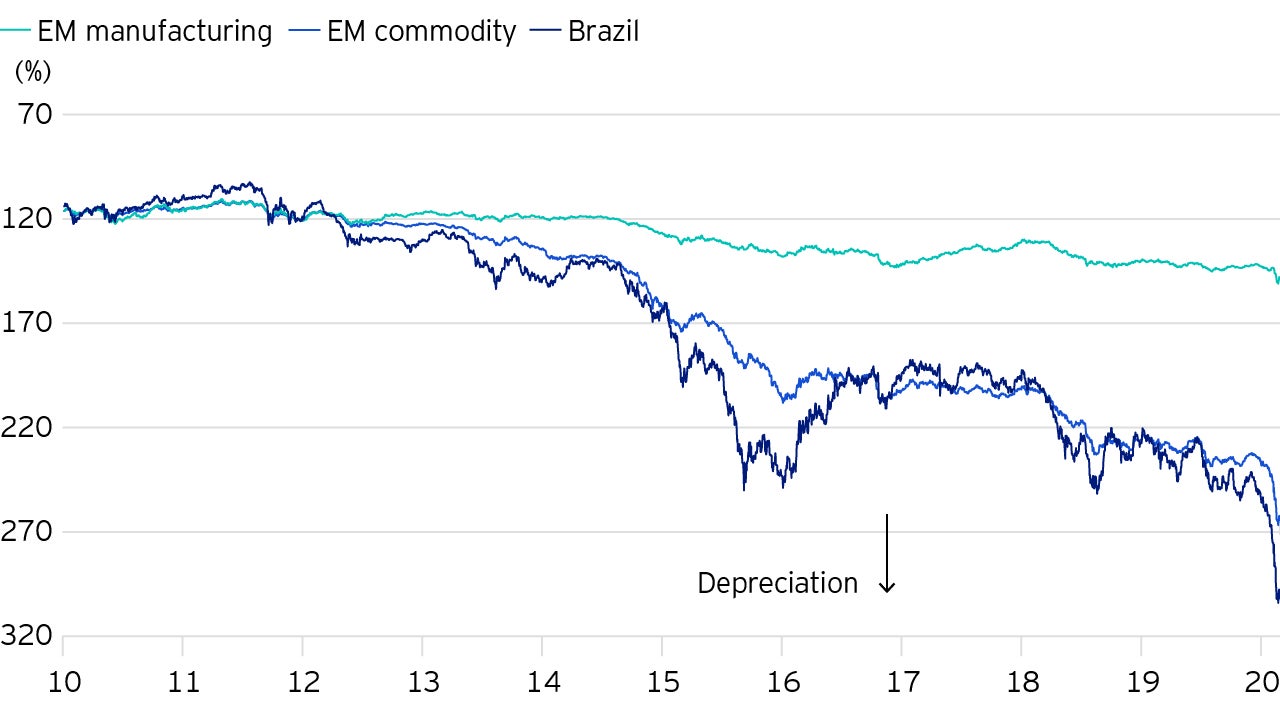

Beset by the coronavirus outbreak, returns of Brazilian equities have contracted by 36% since the beginning of the year, compared with the 11%% retreat of the broad MSCI EM Index during the same period.2

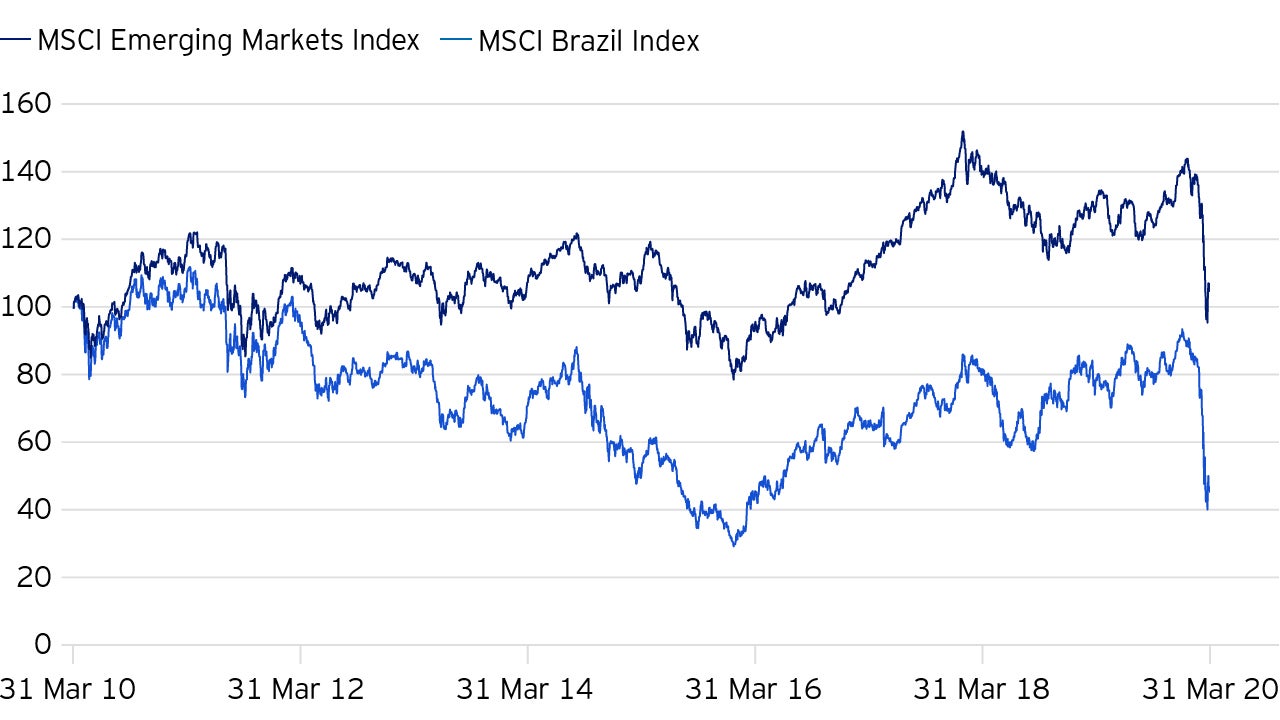

In the past decade, while EM saw a narrow 7% rise in returns, Brazil’s equities took the hardest hit by sinking more than 50%.

The trick in Brazil is timing - and timing is all about appropriate prices.

Self-inflicted ailments

What ails Brazil?

The list is lengthy, but fundamentally we believe these are the most notable self-inflicted inhibitors to more sustainable and higher levels of growth in Brazil.

Private investment/productivity.

Investments accounted for only 15% of Brazil’s GDP in 2019, around the same level of the past four years.

Foremost, growth suffers the most from unreasonably low levels of private investment.

In Brazil’s case, this has remained for decades at levels that are unable to beat back economic asset depreciation and support sustainable growth.

In all developing economies, private investment is the lubricant to income growth, both directly and through productivity improvements.

Fiscal Challenge

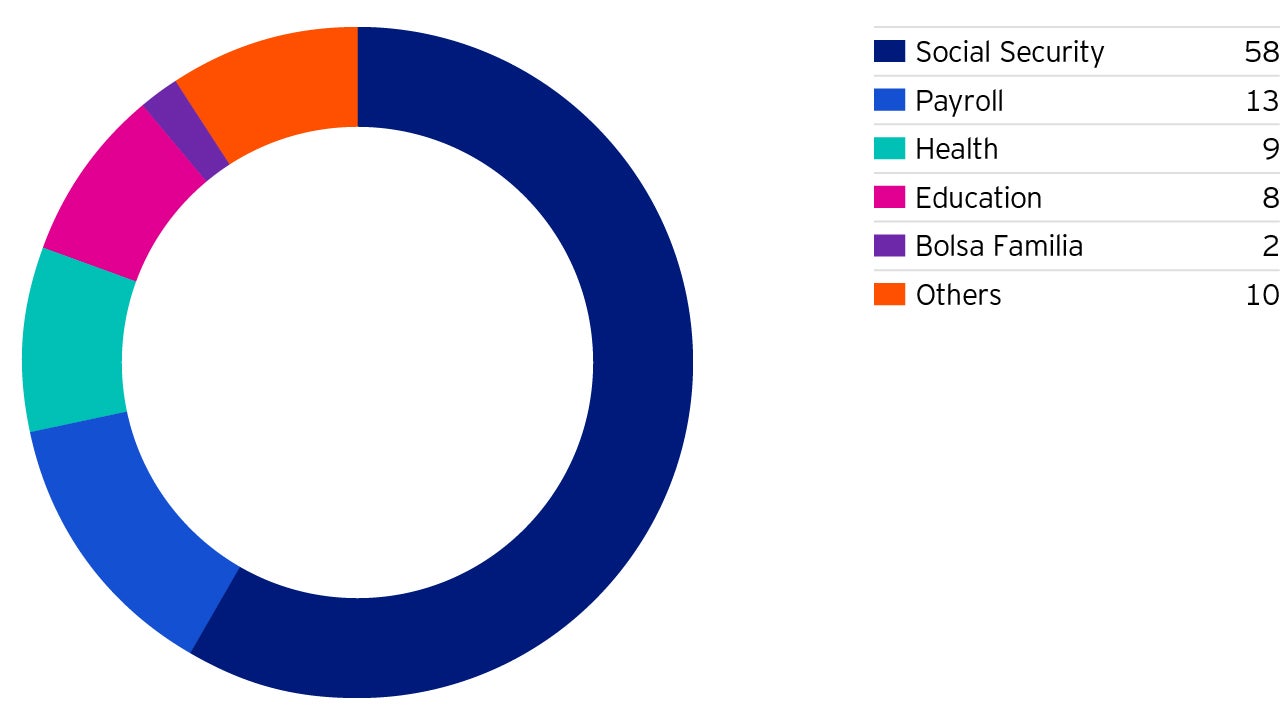

Brazil struggles with an outsized state, and one that spends in what we believe are all the wrong places.

Brazil's clumsy state and prohibitive cost of capital have been crowding out private investment for years.

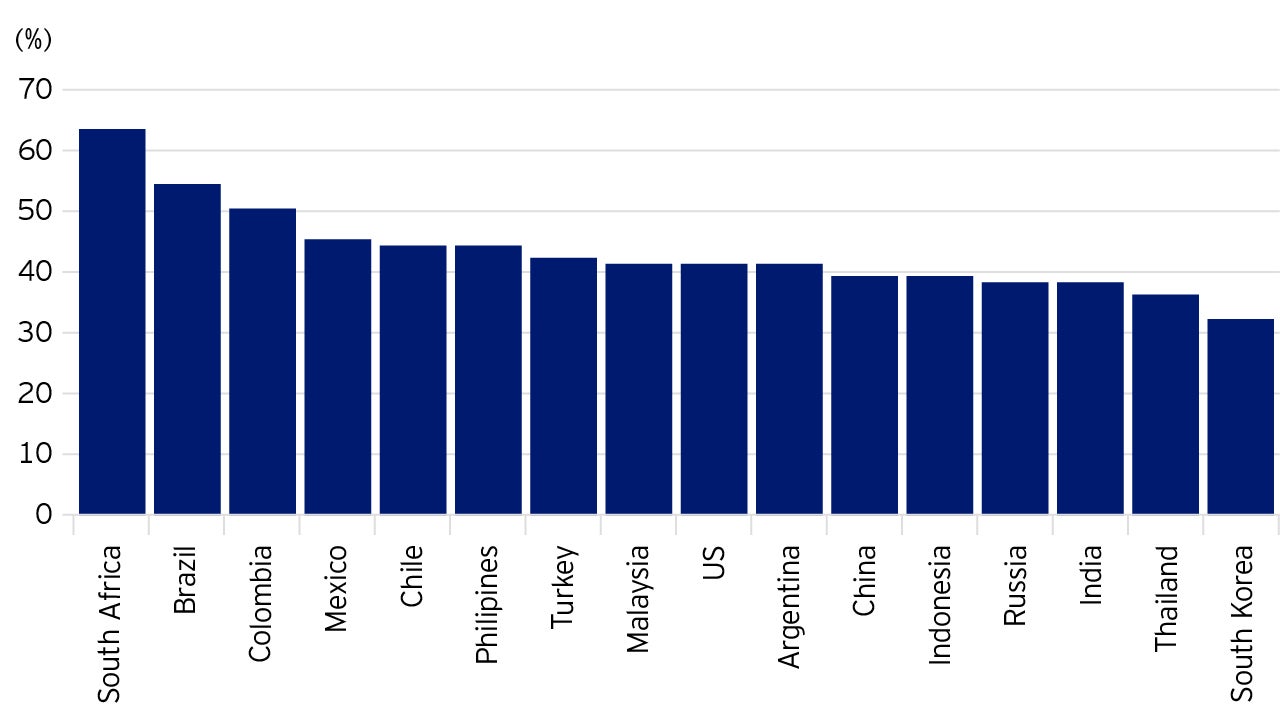

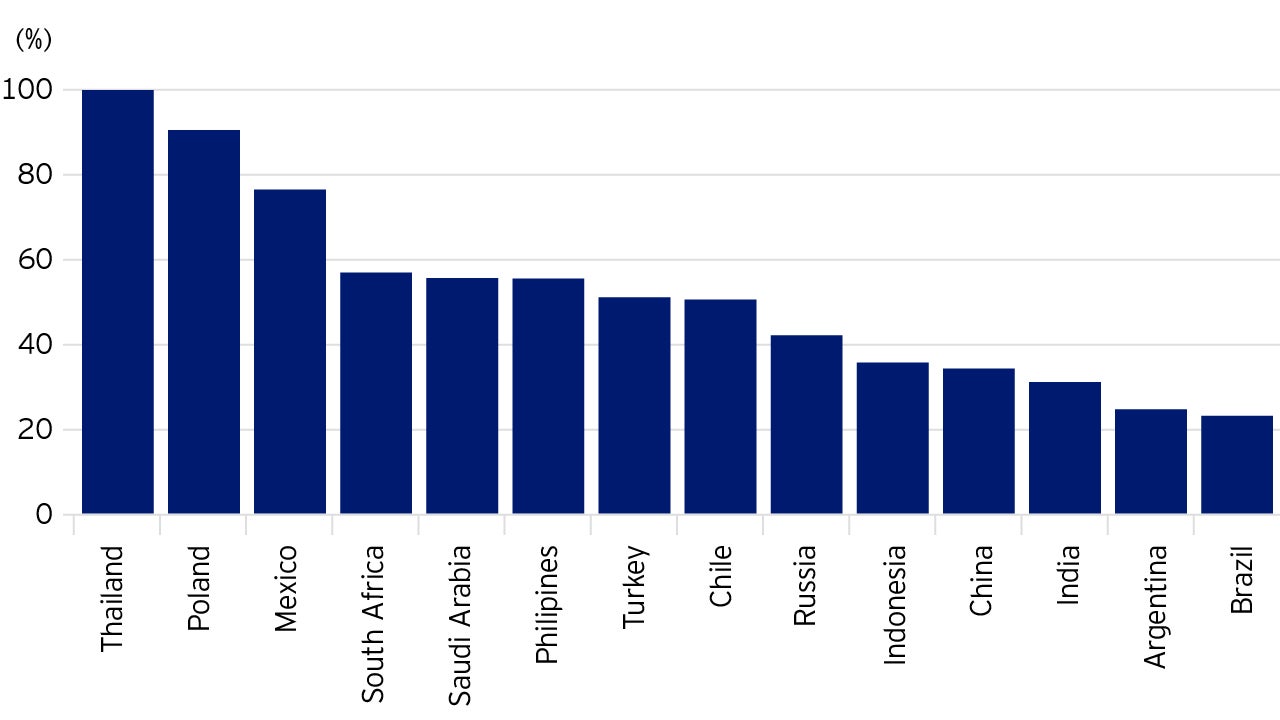

At 38% of GDP, 3 Brazil's fiscal expenditures topped all major EM countries in 2019, while its private capital investment has been steadily falling in the past decade, hovering around 15% of GDP in 2018.4

Ever since President Fernando Henrique Cardoso administration’s passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Law in 2000, Brazil has been preoccupied with taming fiscal expenditures.

After recklessness during the Dilma Rousseff administration, there have been notable legislative efforts to return Brazil to fiscal sustainability.

Markets cheered both the impeachment of President Rousseff in 2017 and the hard-won passage of social security reform in 2019.

Social security reform which, alongside caps on real budgetary growth over the next 15 years, was estimated to help Brazil onto a path to debt sustainability.

However, the cyclical budgetary requirements of the coronavirus and the political inability to enact more material cuts in civil servant wages (which account for 13% of total fiscal spending5) mean that the outsized fiscal deficit will likely continue to crowd out private sector investment.

Despite a big state presence, Brazil has been spending in the wrong places.

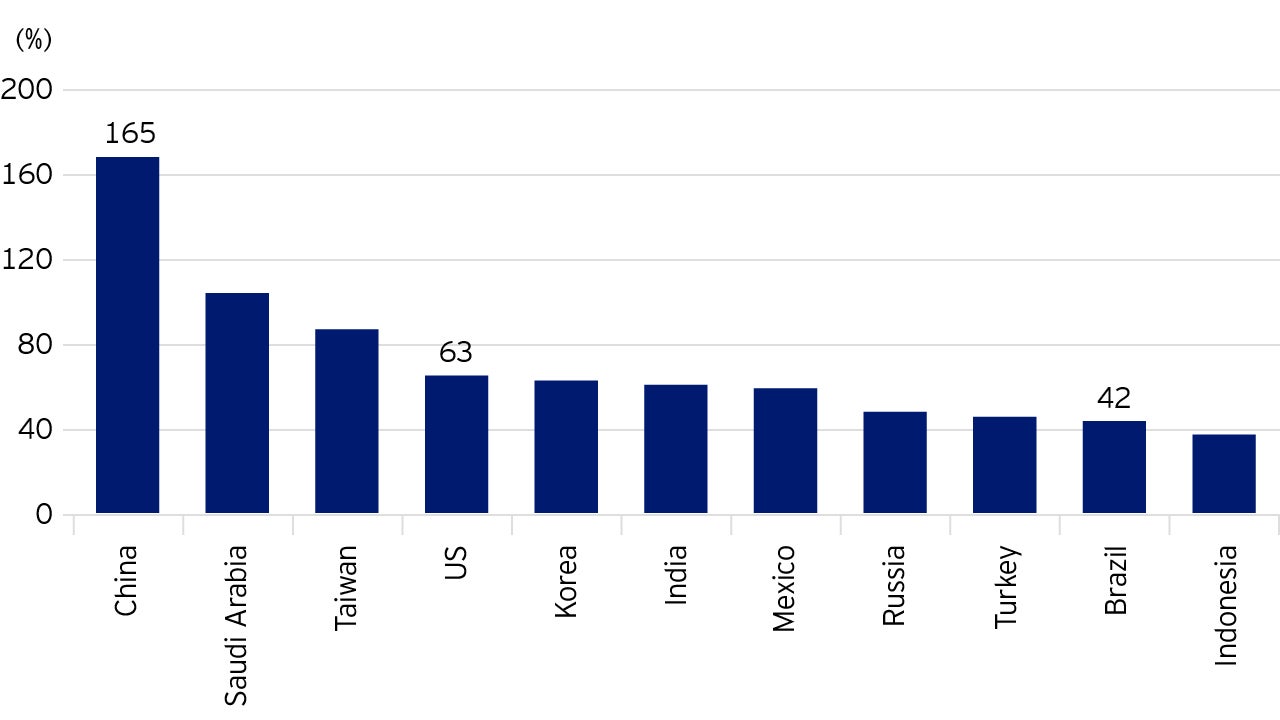

Brazil has only about 42% of its GDP in government capital stock, well below China’s level (165%) and that of most of its other EM peers.

Brazil also has one of the lowest levels of infrastructure investment, which is crucial for eliminating production bottlenecks and expanding access to social services.

Specifically, Brazil has invested less than 2% of its GDP over the past two decades in infrastructure, while the rest of Latin America spent 5%, on average, and the other EM countries devoted more than 6% of their GDP.

A recent survey6 found the Brazilian population to be the most dissatisfied with their infrastructure services among all the 28 major economies covered in the study.

Rent seeking and state directed capital allocation

Big government extends beyond the budget in Brazil.

The influene of the leviathan is nearly everywhere, creating distortions in capital allocation.

Brazil maintains direct ownership of many of the pillars of industry and much of the banking industry.

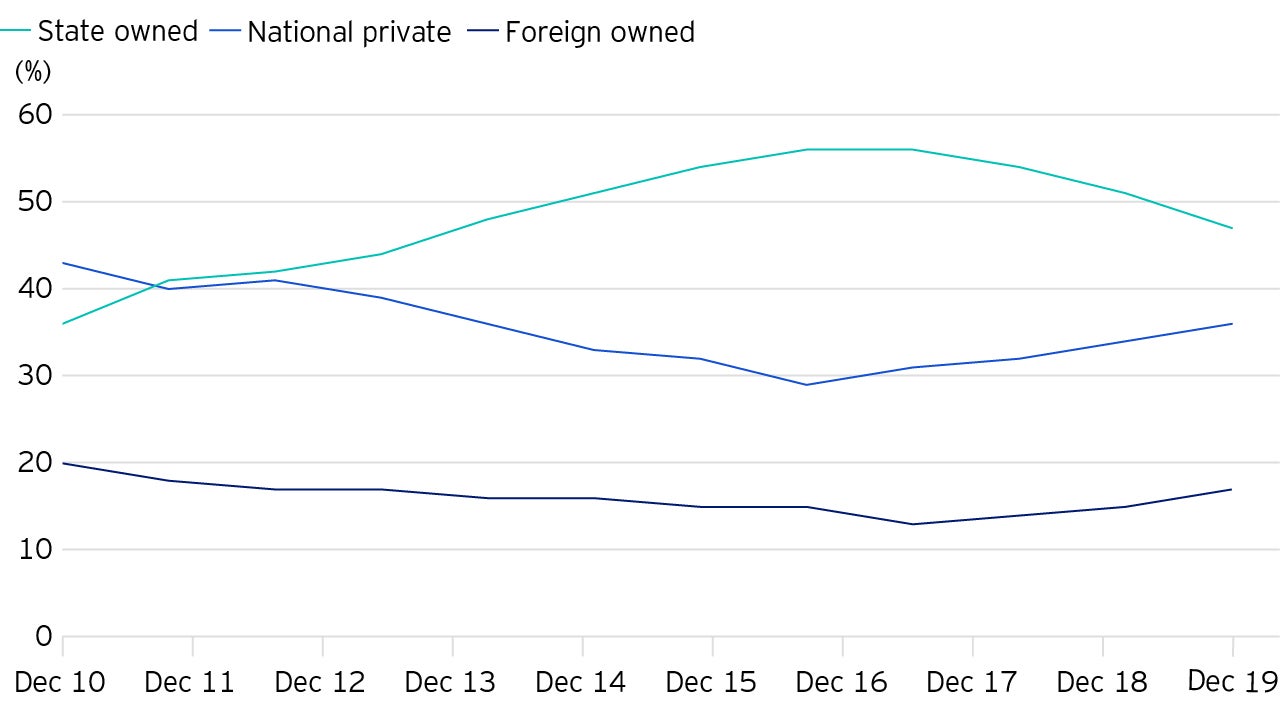

Although there has been a retreat post-impeachment of President Rousseff, public sector credit still represents 47% of total bank credit.6

The state’s power to influence capital allocation runs far deeper than its direct intermediation.

Private-sector banks (including foreign-owned banks), which currently contribute to about 53% of national loans, must comply with directed (“earmarked”) lending requirements, which represent nearly 30% of total private-sector bank lending.7

Brazil is also notorious for its unusual level of administrative complexity, including having one of the most challenging tax systems of any significant economy in the world, featuring more than 80 different taxes at the federal, state and municipal levels.

All these forces amplify the problem for the private sector and result in corporate incentives focused as much on rent-seeking concessions as on market-driven competitiveness.

It is a testament to the leviathan power that Brazil has such limited competition in product markets and thereby structurally low levels of productivity and innovation.

The dual economy/inequality nexus

Just like India, Brazil has a pronounced dual economy, perpetuated by extremely unequal income distribution.

The state’s hefty tax revenues amount to as much as a third of its GDP, 8 a level like that of European welfare states.

But unlike in Europe, where taxes and wealth transfers greatly reduce inequality, Brazil’s distorted social spending exacerbates the dual-economy circumstance.

The imbalance is epitomised by the country’s problematic distribution of healthcare and education resources.

Specifically, Brazil’s total expenses associated with healthcare added up to 8% of its national expenditures,9 or 12% of GDP in 2016, 10 above the global average of 10%.

However, its private sector health care, which stands as the second largest in the world after the US, 11 and accounts for 2/3 of Brazil’s total health expenditures, 12 is available to only 20% of the Brazilian population.

In turn, the remaining population is left to suffer because of insufficient public sector disbursement.

Education is the other widely recognized structural problem in Brazil, and it is also a derivative of the country’s dual-economy structure.

A typical Brazilian student spends less than eight years at school, compared to the 8.5-year average across Latin America.13

Brazil’s education expense is overwhelmingly skewed towards tertiary education with strong “meritocratic” public universities, which are free and are populated by the upper middle class and the wealthy.

On the other hand, the poor are relegated to private universities with not only lower quality but also expensive tuitions.

Brazil's socioeconomic inequality has also decimated its growth momentum

While income inequality across Latin America fell partly as a result of labour market shifts, inequality in Brazil has been rising since 2014, with Gini coefficient/index hitting 0.54 as of 2018.

Although by some definition more than half of Brazil's population is considered middle class, 14 the richest 10% of Brazilians control about 55% of national wealth, and the top 1% own 28%.15

In recent years, inequalities have been further aggravated by President Jair Bolsonaro decision to slash the landmark poverty reduction programme ‘Bolsa Familia’, which has never cost the government more than 0.5% of GDP since its creation in 2003 and helped alleviate poverty for 13.5 million families through conditional cash transferring.16

The closed continental economy

A final noteworthy problem in Brazil is its deliberate insularity from global competition.

Brazil has been designed - since the military dictatorship in the 1960s - as an import substitution economy.

After decades of this experiment, the population has been left with protected industries (capital equipment, automobiles, ‘white goods’) that amplify inequality and comparatively high price, low-quality products.

There is an enormous opportunity for this continental sized economy to open and receive much needed foreign direct investment.

Opportunities for Brazil

As a result of all this, we believe that Brazil will likely continue to suffer from self-inflicted obstacles to growth and progress.

Nevertheless, there remains hope.

The President’s cabinet - and in particular the very capable Minister of Finance, Paulo Guedes - has a very ambitious programme of structural reforms intended to address many of the most pressing obstacles outlined above, including deepening fiscal responsibility (with durable cuts to public sector wage expansion), tax reform, privatisation of non-core state assets, and ultimately opening up Brazil’s hermetically sealed economy to greater foreign competition and investment.

We believe it is unlikely that the most ambitious parts of this programme will get enacted, given the current focus on battling the coronavirus, as well as the lingering political opposition to such deep-seated reform because vested interests are particularly against wholesale tax and administrative reforms.

But, as noted, we still believe there remains some hope.

It is a powerful observation that the only time real structural change happens is when there is a moment of crisis, when the alternatives are limited and the pressure most intense.

Brazil is one of these periods, coming after a long and extremely painful recession over the past half-decade.

We expect more to come.

Still, we do not invest in hope, but rather from the result of reasoned analysis.

Even in the absence of further reform, Brazilian equities are remarkably cheap, in our view.

While Brazil will not be able to escape the “gap” year in growth and corporate earnings that this dreaded virus has thrust upon all global equities, there will eventually be a recovery.

And the survivors - those with ample balance sheet capacity to invest in brands, channels, capacity and innovation - will win even more materially as competitors exit or fade into greater obscurity.

In addition to Brazil’s having attractive equity valuations, its currency is near rock bottom, in our view.

The Brazilian real has fallen sharply this year (-25% YTD17), compounding the close to 70% decline in the past five years.

Against the favourable environment of structurally lower interest rates in Brazil, stocks look broadly attractive.

Ultimately, we are investors in what we consider to be great companies and not really countries.

While Brazil may likely continue to disappoint the optimists, we do not think its equities will disappoint the cautious.

Footnotes

-

Footnotes

1 Source: Bloomberg, MSCI, as at 18 June 2020.

2 Source: Bloomberg, MSCI, as at 18 June 2020.

3 Source: IMF, 31 December 2019.

4 Source: The World Bank, 31 December 2018.

5 Source: National Treasury, JP Morgan, 31 December 2019.

6 Source: Bank of America, 31 December 2019

7 Source: Bank of America estimates, 31 December 2019.

8 Source: JP Morgan, National Treasury of Brazil, 31 December 2018.

9 Source: JP Morgan, Brazil government, 31 December 2018.

10 Source: JP Morgan, data as at 31 December 2016.

11 Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

12. Source: JP Morgan, data as at 31 December 2016.

13. Sources: JP Morgan, HDR – UNDP, 31 December 2018.

14 Source: CIA, the World Fact Book, updated 1 April 2020.

15 Source: World Inequality Report, 2018

16 Source: JP Morgan, as at 30 November 2019.

17 Source: Bloomberg as at 18 June 2020.

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested. As a large portion of the strategy is invested in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in the value of the strategy. The strategy may invest in certain securities listed in China which can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect the liquidity and/or the investment performance of the strategy. The strategy invests in a limited number of holdings and is less diversified. This may result in large fluctuations in the value of the strategy.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Important information

-

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.