Inflation prospects after the coronavirus bailout

John Greenwood. Chief Economist, Invesco Ltd and Adam Burton. Assistant Economist.

Key takeaways

1. Money in the hands of the public creates inflation, not money on the books of the central bank

2. The Fed’s balance sheet has swelled by almost 40% so far this year

In recent days some market commentators have been expressing acute anxiety about the central bank response to Covid-19, and special concern that these actions will bring about a period of high inflation.

It is true that the recent actions of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and other central banks have been unprecedented in speed and scale.

For example, the Fed balance sheet has increased from US$4,158 billion on 26 February to US$5,812 billion on 1 April, or by over US$1.65 trillion in March 2020 alone, an increase of almost 40%.

Other central banks will be following close behind.

We believe, however, that this is not necessarily inflationary; while the size and the duration of asset purchases by the Fed are important, what matters even more is the impact of these purchases on money held in the commercial banking system, or broad money.

For it is money in the hands of the public that creates inflation, not money on the books of the central bank.

Money creation

Before we discuss the effects of asset purchases by the Fed on the broad money supply, it is important to understand the mechanics of money creation, and the various ways in which a fiscal deficit can be financed, and whether those methods are inflationary or not.

In a modern economy, money is mostly created by commercial banks making loans.

When, for example, bankers grant a mortgage loan or business loan, they write up a new asset and credit the deposit account of the borrower.

They do not need to have the funds lying idle under the counter or in a cash account.

They literally create the money out of nothing.

In the old days, money created like this used to be called “fountain pen money”1 because it was created by the banker sitting at his desk writing in a ledger with his pen.

Today the same result is achieved not by pen and ink, but electronically.

Conversely, when loans are repaid the borrower’s deposit account is debited and the loan balance outstanding is simultaneously reduced.

In this sense, money is constantly being created and destroyed in the banking system.

As the economy grows, more money is steadily created, increasing the stock of money in the system.

The outstanding deposit balances circulate as IOUs between firms and individuals.

A similar process occurs when banks buy or sell securities.

When they purchase securities, they credit the deposit account of the seller, creating money.

Conversely, when banks sell securities, they debit the account of the buyer, reducing the amount of money outstanding.

Note that the central bank has only a marginal involvement in this process - usually by setting a key interest rate which guides lenders and borrowers as to how much to lend or borrow.

Breakdown – help needed

However, when the normal process of money creation by commercial banks breaks down, then central banks need to step in to stabilise the system.

For example, in 2008-09 there was a sudden panic due to widespread mistrust of some large financial institutions such as Lehman Brothers, AIG and others, inducing many to sell risky assets in order to hold cash or deposits.

In short, the demand for money increased abruptly and banks - who were part of the problem at that time - were unable to provide it.

The central banks, and particularly the Fed, therefore needed to step in and provide cash or deposit money or liquidity by purchasing securities in the markets - a process known as quantitative easing or QE.

Numerous other ways of injecting money into the system were also introduced.

The current credit squeeze has also been created by a similar dash-for-cash.

Faced with the sudden onslaught of the coronavirus and the prospect of lockdowns leading to the collapse of economic activity, disruptions to the payments system due to businesses being shut down, bankruptcies and rising unemployment, any sensible business or individual immediately started calculating what funds they would need to tide them over until recovery came.

Raising cash

This prompted a widespread sale of risky and not-so-risky securities, to raise cash.

As in 2008-09, it would have been impossible for the banks to meet the short term need for liquidity.

Consequently, central banks have once again had to step in and create the cash, deposits or liquidity demanded by firms and households.

Historically when central banks have played this “lender of last resort” role in a market panic, they were able to create the additional funds needed to calm the panic, and after the panic had subsided, they would gradually withdraw the excess cash or deposits from the banking system.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries there were numerous episodes of this kind, and they were resolved - sometimes by large powerful bankers (such as John Pierpont Morgan in the 1907 Panic before the Fed was created), more recently by central banks - without inflation because the excess funds were drained from the system before inflation could take hold.

Inflation outlook

To understand and predict the outlook for inflation after the coronavirus crisis we need to focus on the nexus between monetary and fiscal policy because the injection of large amounts of funds is being created in two main ways: by expansion of central bank balance sheets, and by huge increases in government debt and deficits.

For clear thinking in this area it is helpful to separate monetary policy and fiscal policy.

- Actions taken by the central bank to satisfy the sudden demand for cash to settle payments create money. Historically the instruments purchased or used as collateral for loans by central banks were predominantly short term and naturally self-liquidating (bills of exchange, Treasury bills etc.).

- Funds provided by the government through fiscal actions to tide firms and individuals over the period of economic dislocation are debt. These instruments will tend to be of a long-term nature and will only be repaid slowly over time through the tax system.

We therefore need to examine to what extent and under what circumstances government debt will be converted into money.

Fundamentally there are only three ways to finance a government budget deficit: by taxation, by borrowing, or by printing the money.

- Taxation is a direct transfer from private sector to public sector with no gain to overall spending, so it is non-inflationary (unless money is simultaneously being created too rapidly). The main effects are on the composition of spending (GDP) or on the distribution of national income. In current circumstances, budget deficits are not going to be financed by taxation to any significant degree so we can set this possibility aside.

- Borrowing is done by issuing government debt instruments, and it will be non-inflationary only if the funds are borrowed from the non-bank private sector in such a way that they do not create money. When the government borrows in this way, the main effects are on the capital markets - sometimes raising rates and crowding out private sector firms or households that would otherwise have borrowed those funds. However, as we saw last year in the US, when banks buy government securities, that creates money which in turn boosts total spending. If continued for long enough, this will lead to inflation. In the wake of the coronavirus crisis, therefore, the authorities will need to manage carefully the amount of government debt purchased by commercial banks if they are to limit broad money growth.

- “Printing money” has three possible interpretations.

- It can mean central bank purchases of government securities in the primary market (buying bonds directly from the government) which is what we typically see in places like Venezuela, Zimbabwe etc. However, in modern economies such practices are generally outlawed and therefore unlikely in the next year or two, but the possibility cannot be ruled out.2

- “Printing money” can result from a policy of either keeping market interest rates too low so that banks are encouraged to lend more than they otherwise would, or keeping the exchange rate too low (i.e. undervalued), thus generating a surplus on the balance of payments that produces an influx of funds from abroad. Both more lending and an inflow of funds from abroad create additional deposits (equals money) on the liability side of commercial bank balance sheets.

- Even with normal market interest rates (as arguably last year in the US), substantial purchases of government securities by the banks can amount to money creation.

Bringing all of this together, what have the effects of the actions undertaken so far by the Fed in response to Covid-19 been on the broad money supply?

Money supply

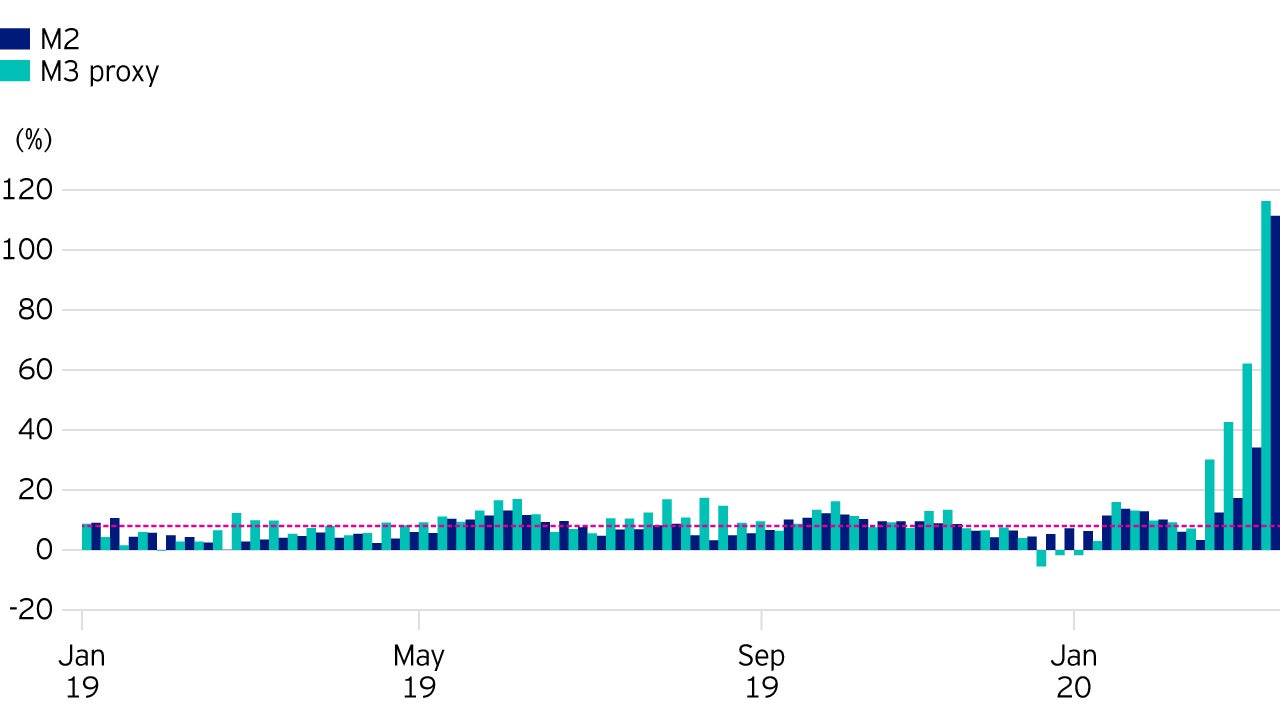

Since the beginning of the year (2020), the balance sheet of the Fed has swelled by almost 40%.

Because the Fed has been buying securities from non-banks - and there have been large drawdowns of credit facilities - there has been an immediate and striking impact of the broad money supply.

In the four weeks to 23 March, broad money has been growing at over 60% per annum on an annualised basis.

If this growth rate of the broad money supply was to continue for a significant amount of time, say six to twelve months, then inflation in the US in the medium-term will indeed start moving higher.

If, however, over the next three to six months this growth rate starts to fall to more normal, appropriate levels for an economy such as the US (i.e. around 6-8% per annum), there need not be any significant increase in inflation.

Summary

It is too early to tell if these unprecedented asset purchases by central banks will be inflationary.

Recall that in the period following the global financial crisis, QE was widely thought to indicate the beginning of hyperinflation as central bank balance sheets ballooned to historic highs.

The actions of the central banks in fact only stabilised broad money growth (preventing it from declining), with subsequent inflation remaining below 2% year-on-year in most developed economies.

Footnotes

-

1 This was in contrast to “printing press money” created by the central bank.

2 The purchases of government securities under QE by the Fed, the BoE, the BoJ and the ECB after 2008 were all conducted in the secondary market, not in the primary market. In other words, private sector firms and individuals first purchased these securities with funds derived from savings, and the QE purchases by central banks then replaced their holdings with deposits at commercial banks or credits at the central bank. These were purely monetary operations, not direct loans by the central banks to governments.

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

-

Where John Greenwood and Adam Burton have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.