Central and commercial bank responses to the coronavirus

John Greenwood. Chief Economist, Invesco Ltd and Adam Burton. Assistant Economist.

Key takeaways

1. US commercial banks are now much better capitalised compared to 2007

2. The Fed’s balance sheet could double in size to US$8 trillion

In the past month since the onset of the coronavirus crisis in western developed economies, most of the focus of policy response has been on central banks and on the fiscal authorities in each economy.

This is understandable and valid in the short term, but in the longer run what will matter is how those monetary and fiscal responses impact the wider economy - banks, the non-bank financial sector, the corporate sector and households.

Perhaps the most urgent issue is how quickly the various schemes translate into actual cash in the hands of those who need it. Otherwise the economic damage from the virus will be much greater and more long-lasting.

In this note we review the latest data showing how much four key central banks (US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England and Bank of Japan) have done, and how the US commercial banking system has responded.

At this moment we are unable to comment in detail on the response of other commercial banking systems because only the US provides weekly data for the banking system as a whole, enabling us to see exactly what has happened in an aggregate sense during the month of March and the first two reporting dates in April.

For the other three systems, only data for February are currently available.

Active Fed

The US Fed has had to be more active and vigorous than any other central bank not only to support the US economy, but also because of the special role of the US$ in global trade and finance.

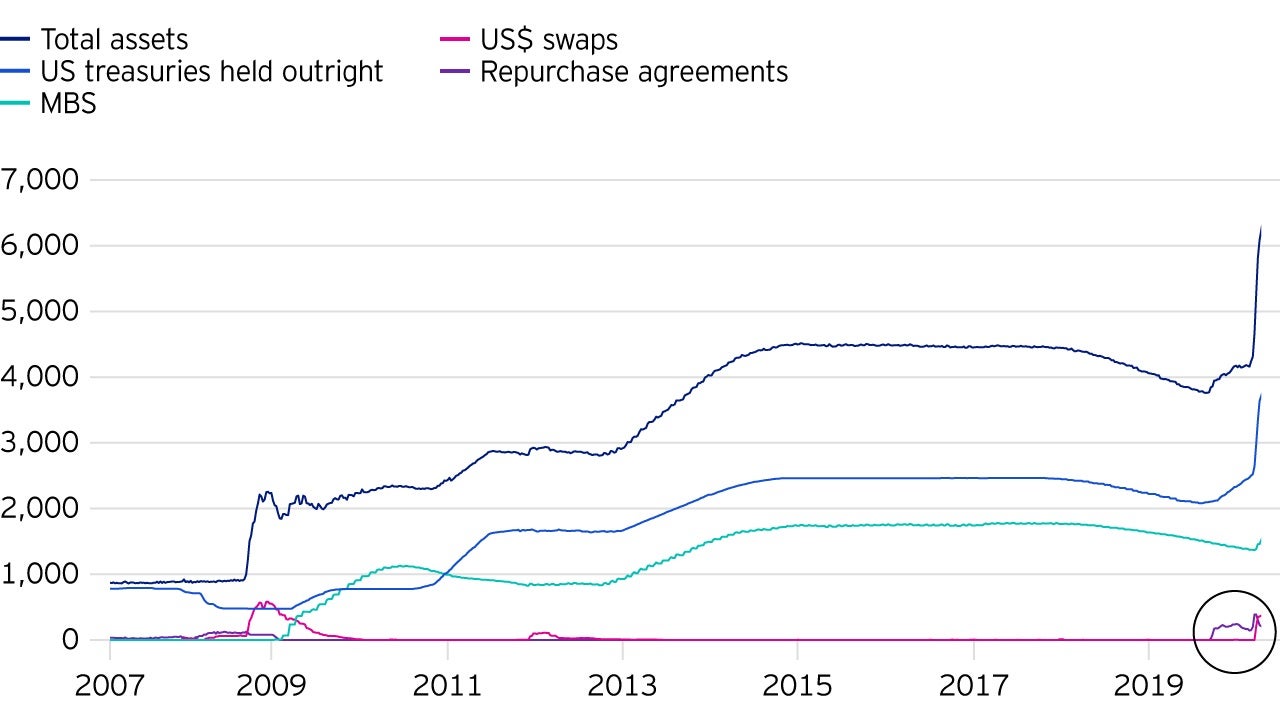

As shown in Figure 1, this has led the Fed, since 26 February, to purchase over US$1 trillion of Treasuries, US$100 billion of mortgage-backed securities, to lend US$388 billion in repos, US$358 billion in US$ swaps with foreign central banks (the latter two both circled), and to provide US$86 billion in support to primary dealers and money market funds (not shown).

In total, between 26 February and 1 April, its balance sheet had expanded by US$1.92 trillion.

In a fundamental sense the Fed is responding to two main pressures.

- There has been a sudden jump in the domestic and worldwide demand for liquidity (i.e. US$ cash assets) by companies to make payments (for wages, supplies, interest and rent) as well as by households (also for supplies, rent, interest on debts, utilities etc.) during the period of lockdown.

- Acute anxieties about the inability to access funds and the ability of counterparties to settle has widened spreads, requiring the Fed to buy securities in different funding markets in an effort to narrow spreads. By doing this it hopes to restore the functioning of these markets for regular purchases and sales as well as for new issuance. Although the Fed has responded with impressive alacrity, it will be some weeks, even months, before normal conditions are restored.

There are numerous Fed programmes that have so far only been announced and are yet to be implemented.

This implies that the Fed’s balance sheet will expand considerably further in the weeks and months ahead.

We fully expect it to double to US$8 trillion over this period, and perhaps even more.

How much more will depend in part on the response of the commercial banks.

US commercial banks

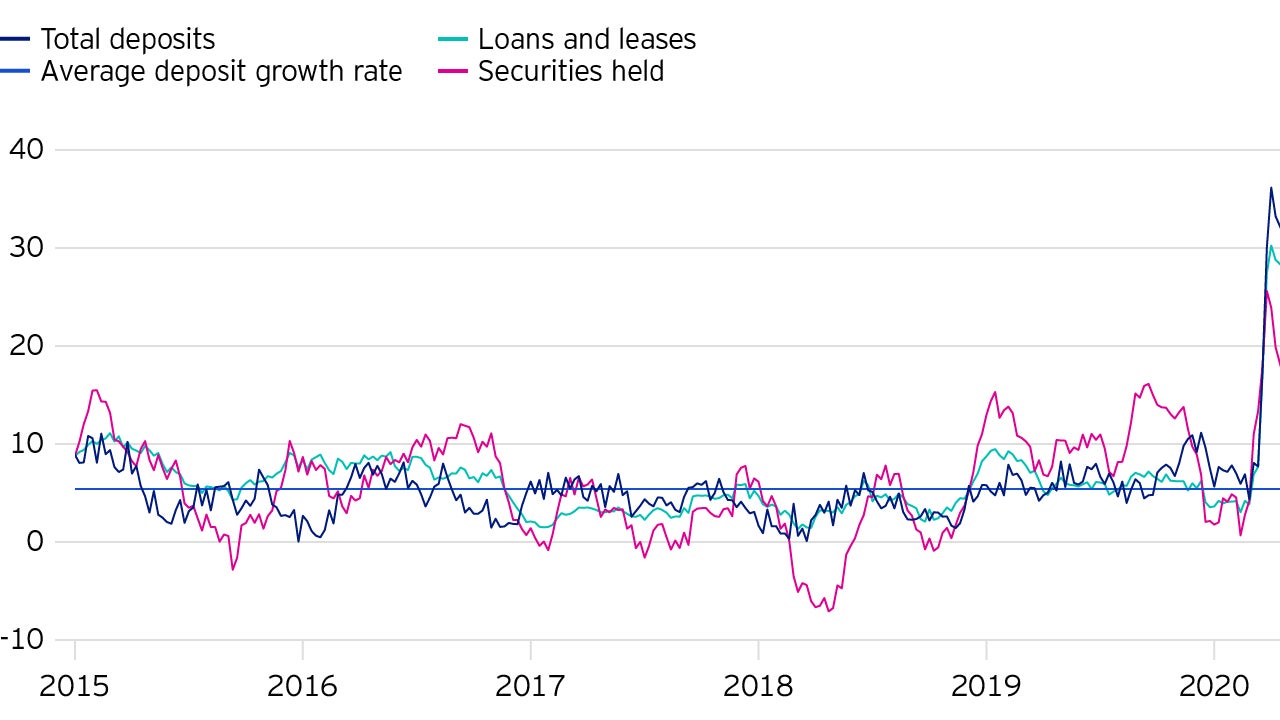

Already US commercial bank loans have jumped markedly since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In total, loans outstanding have increased by around US$600 billion since 11 March, from US$10.16 trillion to US$10.76 trillion, a 6% increase, while securities held have increased by US$63 billion or 1.6%.

On a three month annualised basis to 1 April, these increases amount to 32.4% for lending and 24.3% for holdings of securities, as shown in Figure 2.

On the other side of banks’ balance sheets deposits, measured on the same basis, have surged by 33.9%.

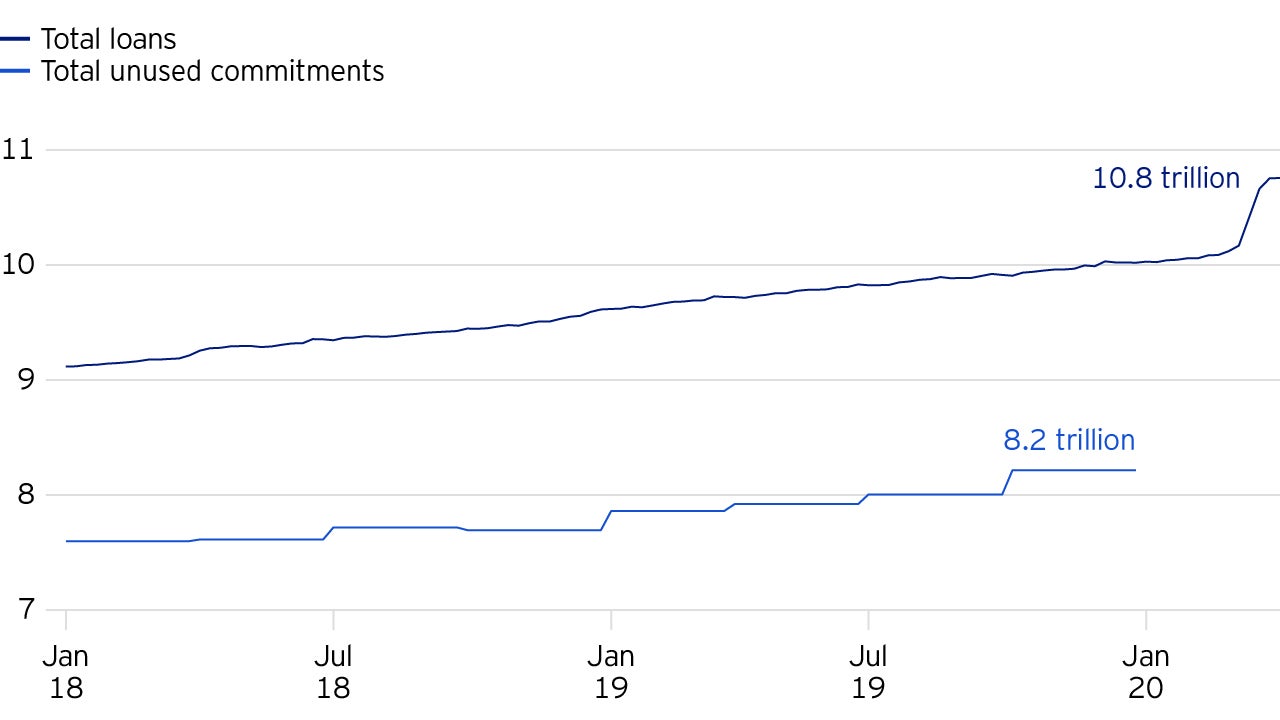

One reason that banks were able to respond so rapidly to the sudden surge in the demand for cash by firms is that large numbers of companies had already arranged credit lines, available to be drawn down when required.

These agreements between banks and their corporate customers are monitored and published by the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) since they constitute a potential call on bank capital.

Total unused commitments, shown in Figure 3, are an off-balance sheet asset of commercial banks, and stood at over US$8 trillion at the end of Q4 2019.

This is a level not seen since the global financial crisis in late 2007.

However, commercial banks in the US are now much better capitalised compared to 2007, meaning that they are able to provide the credit that corporates are demanding as corporate cash flows start to deteriorate.

Going forward, there will likely be a continued use in these corporate credit lines provided by the banks and a sharp acceleration in loan growth.

In addition, the Fed and other regulatory agencies have announced their willingness to allow some degree of forbearance to banks in meeting their regulatory ratios during the Covid-19 crisis.

What’s happening in Europe and Japan?

As we have noted earlier, the Fed in effect has more to do in reaction to Cocvid-19, due to the global use of the US dollar in supply chains.

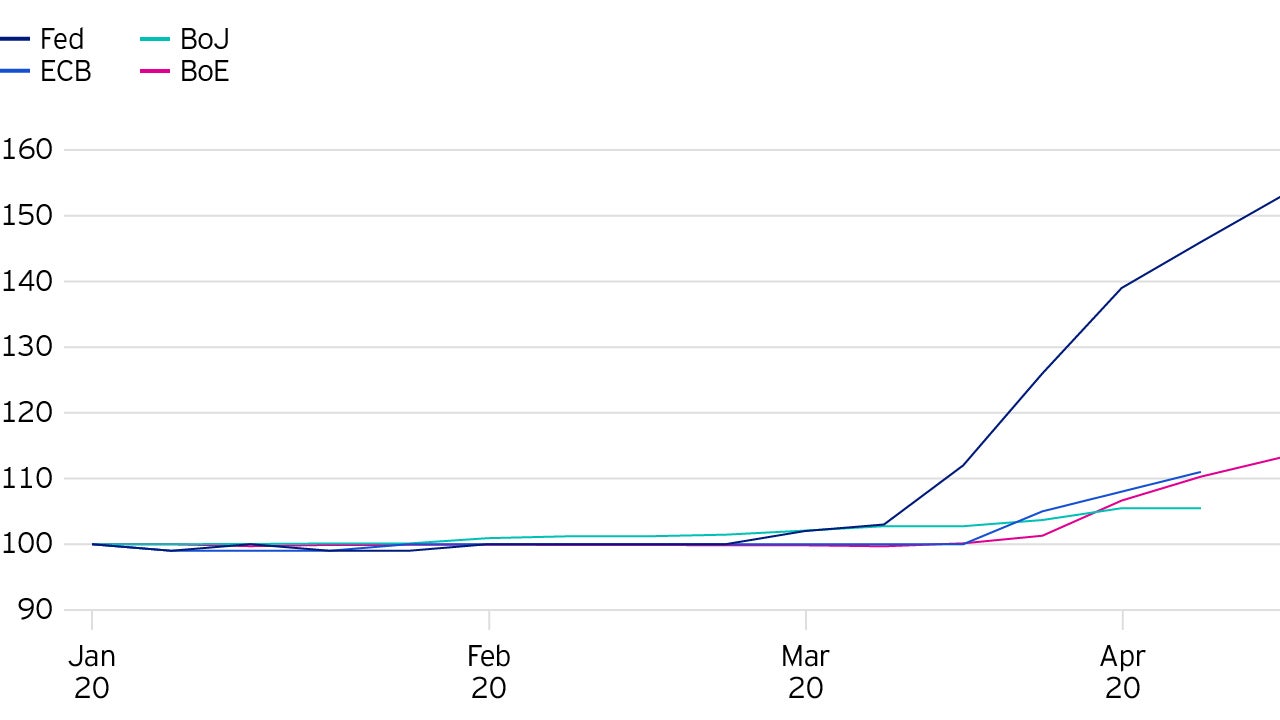

We should therefore expect the Fed’s balance sheet to expand to a much greater degree than other central banks such as the ECB, BoE, or BoJ.

To enable comparisons among central banks Figure 4 below indexes central banks’ total assets to 100 at the start of 2020, up to the latest available data points.

Compared with the Fed, other central bank’s purchases of securities have been expanding by 5-10% in the year-to-date.

Now that commercial banks outside of the US have sufficient dollar liquidity, as evidenced by cross currency bases narrowing, the main focus of these three central banks is to provide enough cash to the private non-bank sector in each economy.

Have the actions of the central banks and the commercial banks been enough to alleviate liquidity problems?

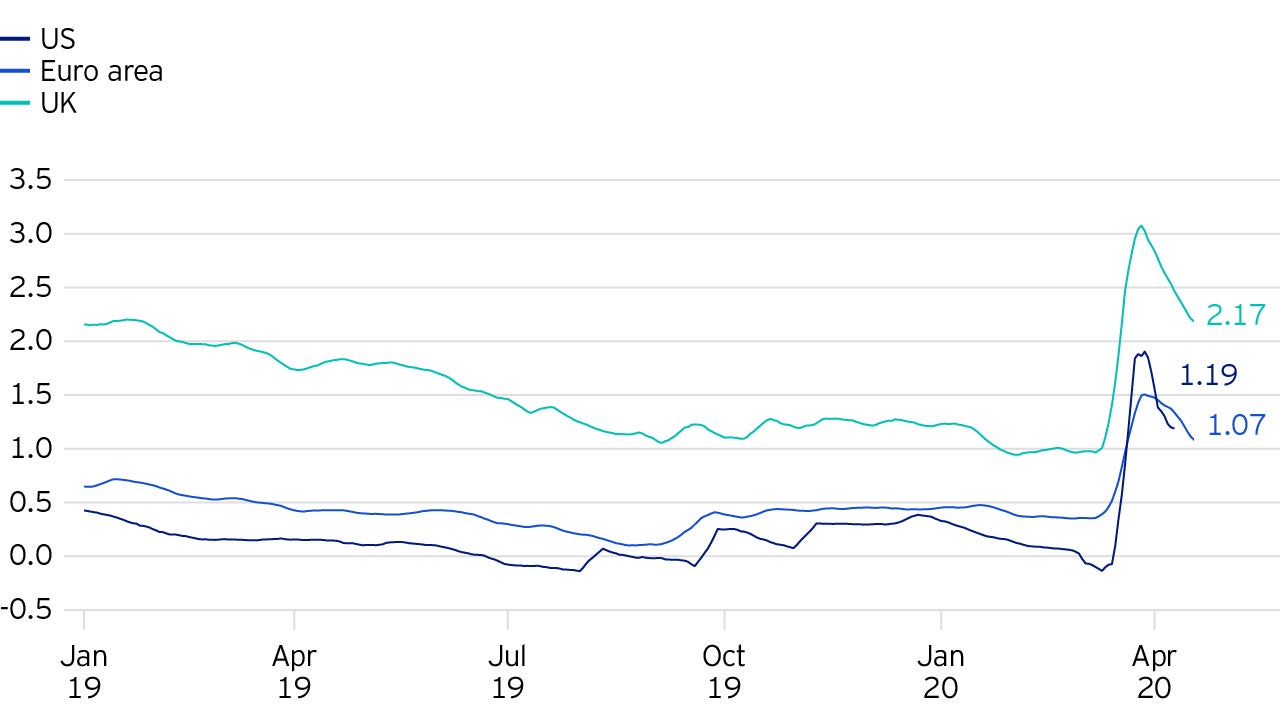

To answer that question, we can look at commercial paper spreads (compared to central bank policy rates) in large, typically liquid markets.

In the US, the Euro area and the UK, commercial paper spreads widened by around 200 basis points towards the end of March, signalling corporate borrowing stresses as businesses and investors made a “dash for cash”.

The central banks have subsequently stepped in with direct purchases of not only commercial paper, but also government bonds and agency securities, which has narrowed spreads to around 120 basis points in the case of the US and Euro-area.

Spreads in the UK remain somewhat wider.

When these spreads return to more normal levels, we will know that markets have returned to normal functioning and that the central banks actions have been enough.

Investment risks

-

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Important information

-

Where John Greenwood and Adam Burton have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, may differ from those of other investment professionals and are subject to change without notice.