Unlocking the power of CLOs

As the financial landscape continues to evolve, investors are constantly seeking new opportunities to diversify their portfolios and generate attractive returns. One such investment that has gained significant attention in recent years is Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLO).

CLOs offer a unique and compelling investment proposition, providing exposure to the dynamic and often resilient leveraged loan market. This white paper aims to provide a comprehensive overview of CLOs, explore their key features, potential benefits, and the factors that make them a compelling investment option.

Introduction to leveraged loans and CLOs

A. What is a Leveraged Loan?

Leveraged loans are loans secured by a first or second lien on the assets of an issuer, rated BB+/Ba1 or lower, and typically floating rate. Other names for these assets may include high yield bank loans, senior loans, or syndicated loans. Leverage loans are typically used as a funding source in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and leveraged buy outs by private equity sponsors. They differ from high yield bonds in that they are not “securities” and are not SEC registered. A bank or group of banks first structure the loan and subsequently syndicate it to a group of lenders (institutional investors, banks, finance companies) in the “new issue” or primary market. Thereafter the loans trade in the secondary market generally between dealers and institutional investors. Leveraged loans comprise the majority of CLO collateral.

B. What is a CLO?

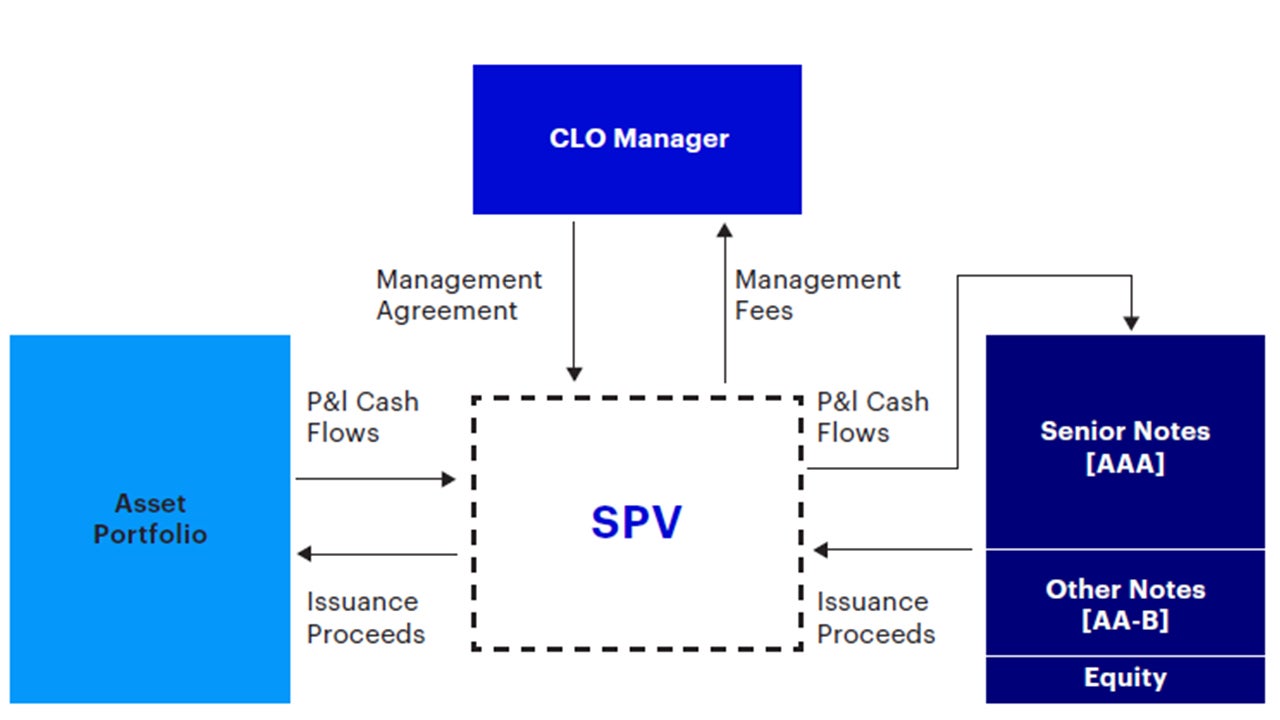

A CLO, collateralized loan obligation, is a special purpose vehicle (SPV) securitized by a pool of assets, including senior secured leveraged loans and bonds. The CLO collects interest and principal distributions from the pool of assets – typically 200-400 unique borrowers – and governs the distribution of these collections based on a waterfall clearly outlined within the CLO indenture.

Before issuance, the CLO vehicle is capitalized via the sale of debt tranches and equity. Once issued, a CLO portfolio is actively managed by a CLO manager who selects the initial pool of assets and may trade in and out of the assets over a typical four-to-five- year investment period. After two years, CLO debt tranches are typically callable. CLO managers receive a fee in exchange for their active management of the portfolio.

Coupon and principal payments collected on the underlying assets (loans) are used to make coupon and principal payments on the CLO’s liabilities (CLO notes). Payments first flow to the highest debt tranche of the CLO structure and continue to the lowest debt tranche. Thereafter, the residual cash flows are distributed to the equity. This is referred to as the “cash flow waterfall”. CLOs are structured to capture the spread, or arbitrage, between income from its underlying assets and payments to its noteholders, which benefits its equity holders.

In certain instances, CLO managers retain a 5% interest in the CLO to comply with risk retention requirements. As of 2018, risk retention for the majority of U.S. broadly syndicated loan CLOs ended, however, European CLOs still require risk retention compliance and U.S. fund managers may choose to retain at least 5% to attract European investor interest. The 5% interest may be retained through holding equity or a mixture of debt and equity.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Source: Barclays Research, 22 January 2021. For illustrative purposes only.

Source: Invesco as of December 31, 2023.

1. Wells Fargo Securities as of December 31, 2018. For illustrative purposes only.

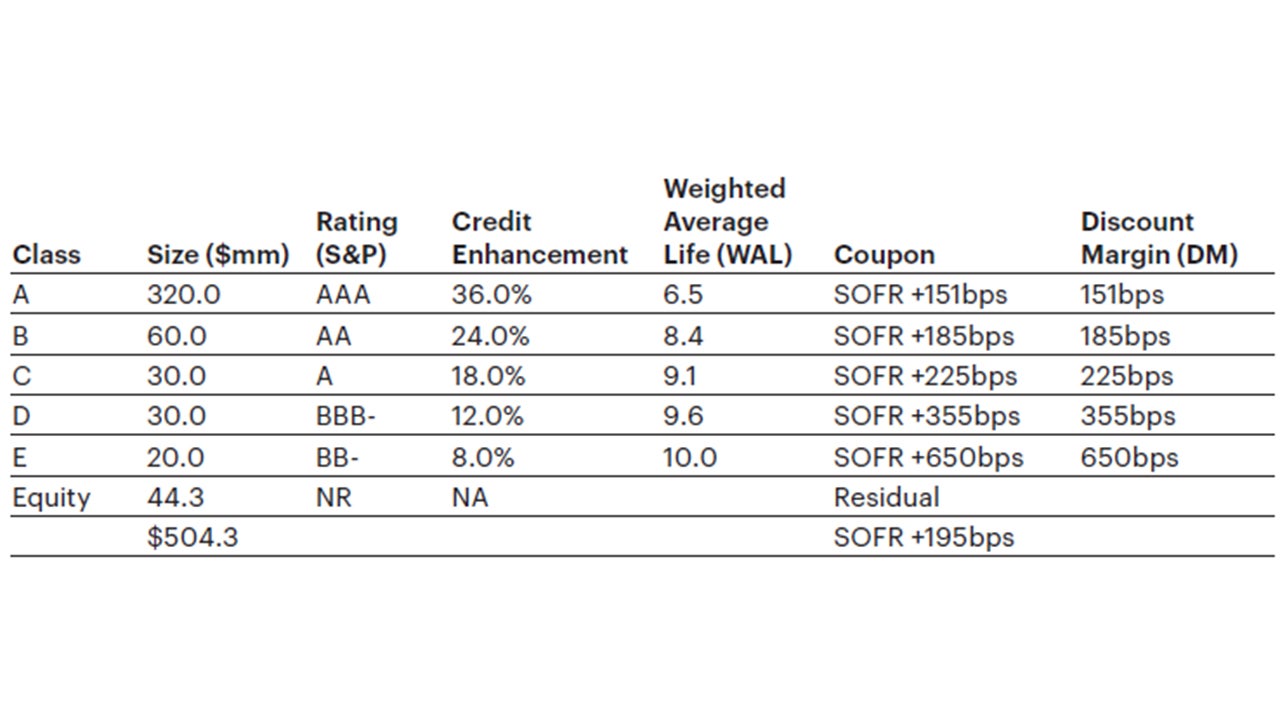

B. Sample CLO New Issue Structure

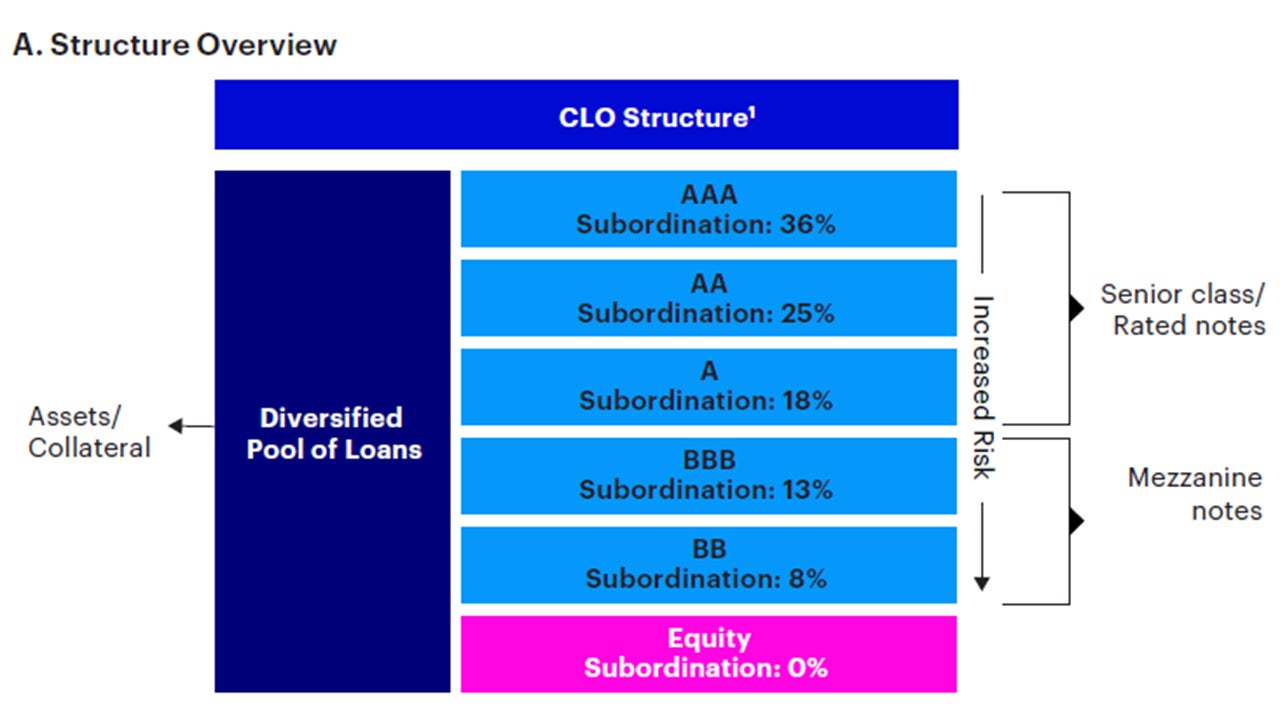

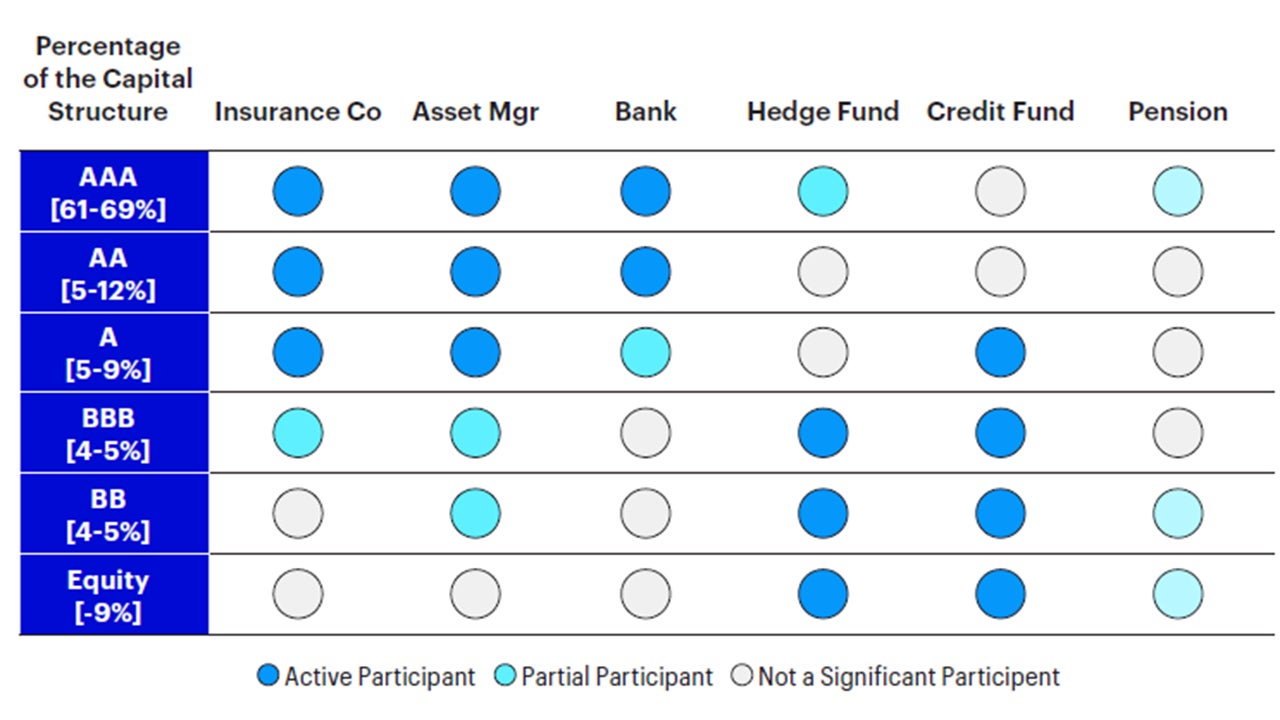

CLO deal structure is comprised of CLO debt tranches and CLO equity tranches. Debt tranches are split by senior tranche (AAA rated) and mezzanine tranches (AA to B rated). Mezzanine tranches include senior mezzanine (AA and A rated) and junior mezzanine (BBB, BB, and B rated). At the bottom of the debt stack is the equity tranche which is not rated and is subordinated to the senior and mezzanine debt tranches. Given the different tranches and economics associated with the structure, investors are able to match their preferred risk tolerance when purchasing CLO liabilities, allowing for many different types of market participants.

Total deal size for a new issue CLO is typically ~$500mm in the U.S. and ~€400mm in Europe where the senior-rated tranche is ~60%-65% of total deal size while equity tranches are typically ~9%-10% of total deal size. Higher rated (i.e. AAA) tranches can withstand greater portfolio losses before any principal loss is taken due to the structure and protections a CLO offers. This is highlighted within the ‘Credit Enhancement” below which illustrates the par subordination or how much par value of the portfolio can decline before the respective tranche takes a principal loss. CLO liabilities, or the coupon paid to the respective debt tranches, are typically floating-rate based on 3-month SOFR and pay out quarterly.

Source: Illustrative Invesco CLO New Issue Structure, May 2024. For illustrative purposes only.

Given AAA tranches are most senior in the structure, they have the lowest risk/return profile. As you move down the capital structure, income levels increase to compensate investors for the increased risk.

Source: J.P. Morgan Research as of December 31, 2023. For illustrative purposes only

Source: Invesco 2024. For illustrative purposes only.

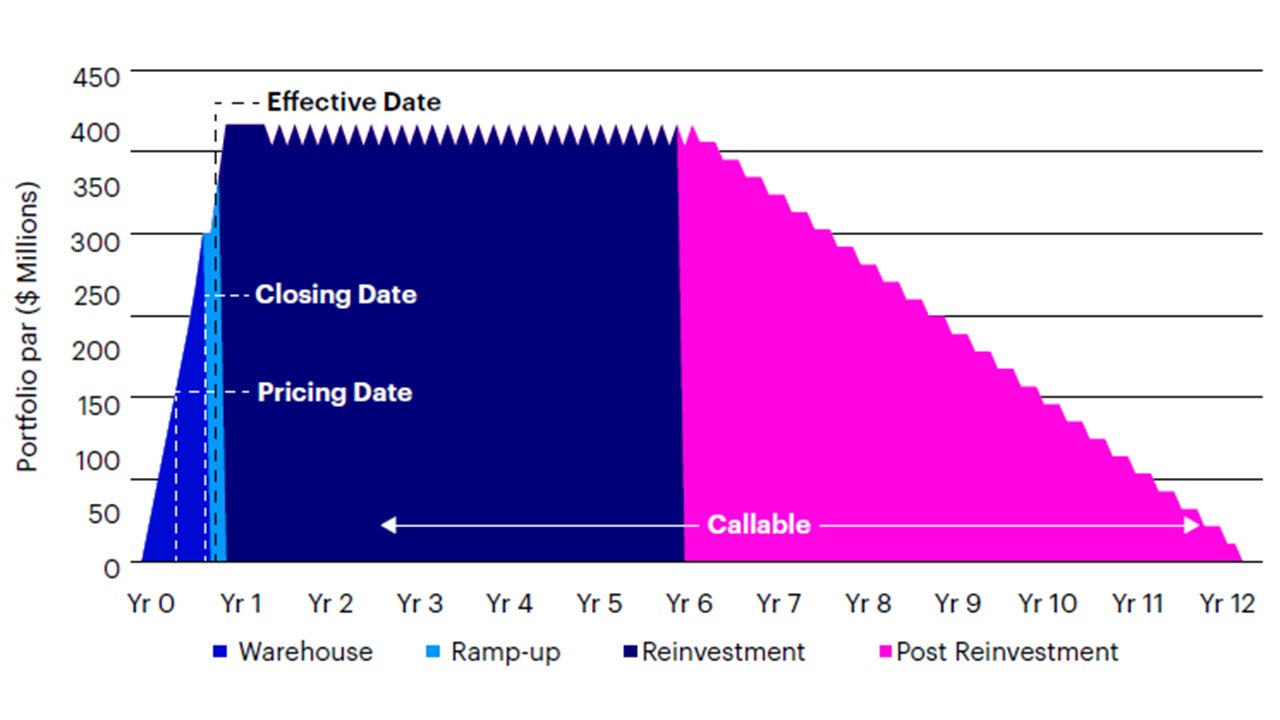

The typical CLO lifecycle includes five stages as illustrated above and detailed below:

- Warehouse Period: The arranging bank provides financing to the CLO manager to start buying assets in anticipation of a future CLO pricing. This typically lasts ~3 to 9 months. Afterwards the CLO warehouse is closed, deal priced, and assets entered into a special purpose vehicle (“SPV”). A CLO can typically price with 50% to 70% of its target par balance.

- Ramp-Up Period: After the CLO’s Closing Date, the Manager purchases the remaining assets needed to reach its target par balance. This typically last ~3 to 6 months.

- Reinvestment Period: Once the CLO reaches its Effective Date (target par reached), the CLO Manager is allowed to actively trade the underlying assets. Income from the underlying assets or sales proceeds can be used to purchase new assets. These purchases are subject to the agreed various tests within the CLO’s underlying documents. Reinvestment periods typically span ~4 to 5 years.

- Non-Call Period: A CLO’s non-call period typically ends after two years. At this point, equity holders can direct the CLO Manager to either call, refi or reset the CLO.

- Amortization Period (Post Reinvestment Period): Post the Reinvestment Period, income received from the underlying assets as well as any sale proceeds, must be used to pay down (“amortize”) the CLO debt tranches. Amortization begins at the highest rated debt tranche. Subject to certain requirements, the CLO may reinvest income and proceeds. Typically two to three years post the Reinvestment Period ending, the CLO is called due to lower equity distributions and rising debt costs.

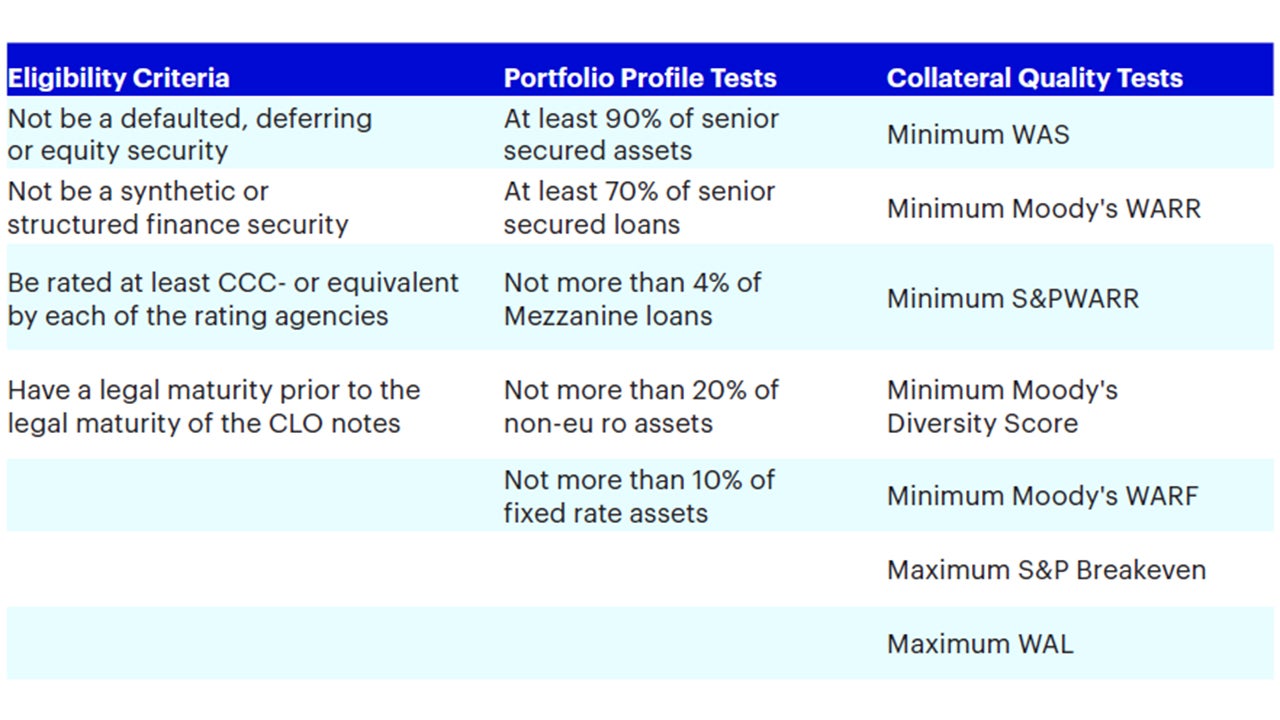

E. Examples of Portfolio Tests

CLOs have a variety of tests to ensure assets purchased are in compliance with the underlying documents.

- Eligibility Criteria: attributes an asset must have to be purchased and held in the CLO

- Portfolio Profile Tests: minimum and maximum concentration test levels governing the diversity and quality of a CLO portfolio

- Collateral Quality Tests: minimum and maximum portfolio test levels governing the portfolio’s weighted average spread, recovery rating, diversity, rating factor, and life. If a CLO fail’s a quality test, it can no longer trade unless such purchase maintains or improves the test. A Manager will often perform a trading plan to work towards compliance.

Source: Invesco July 31, 2024, For illustrative purposes only.

F. Structural Enhancements and Focus on Cash Flow

A CLO’s debt tranches are typically higher rated than its underlying assets and benefit from par subordination and various structural support mechanisms. In order to obtain a higher rating, CLOs have numerous tests in place to protect investors.

Two key coverage tests to protect senior noteholders include the overcollateralization (OC) and interest coverage (test).

- Overcollateralization tests (OC tests): ensures that the principal value of a CLO’s underlying bank loan pool exceeds the total principal value of the outstanding notes issued by various CLO tranches

- Interest Coverage tests (IC tests): measures the ratio of total interest income generated by the underlying pool of assets to the total interest due on the outstanding debt tranches

Noncompliance of either of these tests result in the cash flow of the CLO being diverted away from the equity and junior debt tranches, and towards the senior debt tranches. This begins the amortization of the senior tranches of the CLO and de-leverages the structure until the CLO is in compliance with the coverage test.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Many senior loans are illiquid, meaning that the investors may not be able to sell them quickly at a fair price and/or that the redemptions may be delayed due to illiquidity of the senior loans. The market for illiquid securities is more volatile than the market for liquid securities. The market for senior loans could be disrupted in the event of an economic downturn or a substantial increase or decrease in interest rates. Senior loans, like most other debt obligations, are subject to the risk of default.