Markets and Economy 2021: Light at the end of the tunnel

Despite short term Covid-related risks, recent vaccine news provides valuable light at the end of the tunnel. Paul Jackson, Global Head of Asset Allocation, shares more insights.

Looking ahead into 2020 I believe that the US economy will continue to expand, drawing support from the strength of consumer finances. However, in a US presidential year it seems unlikely that there will be any sustained truce in the trade war with China.

While this is likely to disrupt Chinese exports to the US, other East Asian economies are expected to benefit from a shift in the international supply chain. In Europe, a region blighted with negative interest rates, weak money growth and a poorly designed quantitative easing programme are likely to ensure that the region remains trapped in a low growth environment. Brexit uncertainty continues to cloud the UK horizon with Parliament in gridlock on finding a solution. Until it does, business confidence is not expected to fully recover. Flaws in Japanese monetary policy and slow rates of broad money growth are likely to weigh on the country’s real GDP growth potential.

During the first half of 2019, the US economy grew by just over 2.5% in real terms, slightly ahead of typical estimates for the economy’s potential growth rate of 1.9%. At the same time, the labour market continued to create new jobs with the unemployment rate remaining low at 3.7%.1 However, while consumer spending has been rising at a strong pace, business fixed investment and exports have weakened. Household incomes have been supported by gradually increasing wage gains and high levels of employment, combined with ongoing improvements in consumer balance sheets, according to surveys by the New York Federal Reserve. The main drivers here are rising home prices, rising equity prices, and diminishing indebtedness relative to income.

The strength of consumer finances is an important reason for confidence that the current business cycle expansion can continue for at least another couple of years, in contrast to the leveraged condition of households immediately prior to the financial crisis of 2008-09. In a broad sense, consumers have been gaining at the expense of businesses, as often happens in the second half of a business cycle expansion.

US businesses appear to have passed peak profitability for this cycle. While profits have still been rising, margins have narrowed, and the strength of the dollar has crimped overseas earnings. In the same vein, core capital goods shipments, a lead indicator for business investment, appear to have reached a plateau, and new export orders (from the Purchasing Managers’ Index) have been weakening. Housing continues to make progress, aided by declines in mortgage rates. Again, housing is a lead indicator for numerous business sectors and is therefore encouraging for employment and for the purchases of a range of raw materials from timber to copper and steel. The Conference Board’s measure of business confidence remains at or close to its high for the cycle.

All these indicators suggest that business is not in bad shape but has undoubtedly been derailed somewhat by the global slowdown in manufacturing. I expect the current US business cycle expansion to continue without overheating or being inflationary.

The decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) on 12 September — at Mario Draghi’s last meeting as President of the Governing Council — to resume asset purchases of sovereign bonds at a rate of €20 billion per month (from the start of November 2019) and to cut the interest rate on the deposit facility by a further 10 basis points to -0.5%, was not welcomed by the heads of the German, Dutch, French, and Austrian central banks.

In my opinion, previous bouts of quantitative easing (QE) by the ECB have been a failure largely because they have been poorly designed. If they had been designed to acquire securities from non-banks, this would have raised the rate of growth of M3 in the eurozone much more quickly and to a faster growth rate. This in turn would have increased spending growth across the eurozone, and there would have been no need to resume QE purchases.

Instead, the ECB has decided to resume the same policy with the same failed methodology — buying securities from banks — which in my view will absorb substantial amounts of sovereign debt, essentially in an asset swap with the banks, without creating new deposits in the hands of firms and households, but only on the books of the ECB itself. Therefore, M3 growth will likely continue to be too low and the eurozone is likely to remain in its self-induced weak growth environment, low inflation, and negative interest rate trap.

The Brexit saga continues to dominate political debate in the UK while having negative effects on economic growth by maintaining a high level of “regime uncertainty” — a lack of clarity about the rules, regulations, tariffs, and competitive position of firms after the country transitions to its new relationship with the European Union.

The fluctuations in the Brexit debate continue to be reflected in two key areas: the foreign exchange market for sterling and the domestic investment scene. Elsewhere — such as in the labour market, in personal consumption spending, or in inflation trends — the UK economy has continued to perform much as it did before the referendum of June 2016.

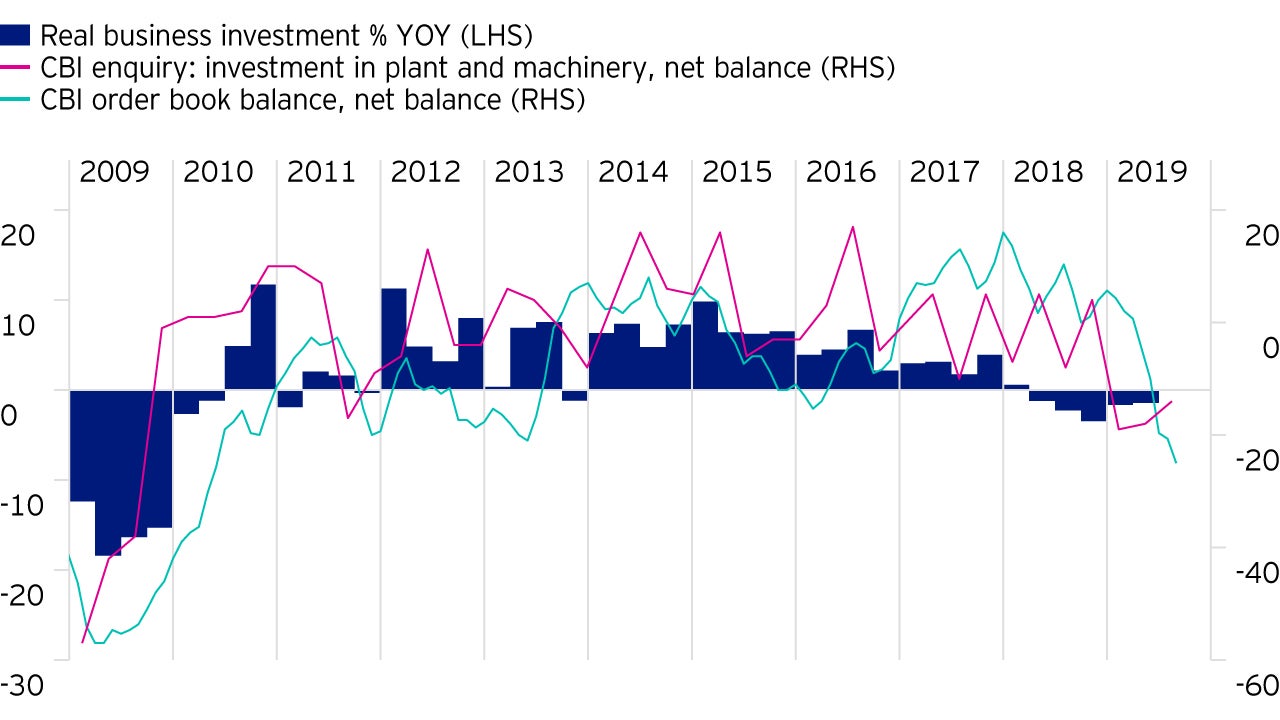

Concerning investment, the downturn in capital expenditures by businesses is abundantly clear in “hard data” such as the gross domestic product (GDP) data on fixed capital formation as well as in “soft data” such as the CBI surveys on plant and equipment expenditure and the state of order books. Unfortunately, these trends seem unlikely to change much until after the political and trading relationships between the UK and the EU are well on the way to resolution.

The trade dispute between the US and China is not showing any signs of easing up. The effects of President Donald Trump’s trade measures on China’s trade and GDP growth are starting to have a significant impact. US imports from China have been falling significantly in recent months. By contrast, US demand for goods made elsewhere in Asia has been rising. Some of the smaller East Asian economies such as Taiwan, Korea, and Vietnam are starting to see production and trade gains relative to China as parts of the international supply chain are shifted towards those economies not yet targeted by the Trump measures.

Looking ahead, given the range of China issues that the Trump administration is targeting —the theft of intellectual property, subsidies to state owned enterprises, and the opening of domestic sectors to foreign competition — it seems unlikely that there will be any sustained truce in the trade war with China. Although the timing of the next US presidential election may encourage Trump’s team to declare victory at some point in 2019-20 and end the trade war, I believe it is more likely that any suspension of US trade measures targeted at China will be temporary.

There are two key factors contributing to Japan’s persisting economic weakness.

First, on the real side, the population peaked in 2010 and the labour force (or working age population aged 15-64) peaked in 1992. Declines in these key figures automatically limit the potential real GDP growth rate.

Second, the explanation for the weakness in nominal magnitudes — inflation, wages, GDP in current prices, etc. — is entirely due to the perennially slow rates of broad money growth. Ever since 1992, Japanese M2 has averaged only 2.6% per year,1 far too low to achieve the Bank of Japan’s 2% inflation target, despite the introduction of quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE) and the central bank’s much-vaunted yield curve control (YCC). Fundamentally, Japan needs a growth rate of M2 of 5-6% per year.1 Unfortunately, Japan’s macroeconomic outlook will not change significantly until this basic problem with monetary policy — buying Japanese government bonds for its QQE programme from the banks (as opposed to non-banks) — is fixed.

Despite short term Covid-related risks, recent vaccine news provides valuable light at the end of the tunnel. Paul Jackson, Global Head of Asset Allocation, shares more insights.

This year has been unique in many ways. Will 2021 be any different? Read more.

What kind of economic recovery can we expect to see in 2021?