Fixed Income Bond bites: Ideas and insights in under three minutes

Bonds had a solid start to the year with a high level of income and a diversifier for stocks. Matt Brill, Head of North American Investment Grade, explains why.

2020’s pickup in sustainability bond issuance has stimulated renewed debate within the IFI investment team and fixed income market participants more broadly as to how much investors should be prepared to pay for a sustainability bond and whether there should be a differential across the different varieties of sustainability bonds.

Although default risk (thankfully low in global investment grade) and recovery rates should be identical for an issuer across sustainability and non-sustainability bonds, suggesting zero fundamental differential, we believe there are several other factors that come into play. Along with the usual drivers of new issue concession (deal size, issuer rating, rarity, sector, market risk appetite, etc.), we believe the sustainability bond program from which a company issues bonds also needs to be assessed.

Our usual integrated ESG analysis (examining an issuer’s ESG characteristics versus sector peers to derive an overall A-E rating with trend) does not fully address sustainability bonds because of the way these bonds target specific projects. An A-rated ESG issuer could theoretically issue a low-quality sustainability bond, and an E-rated ESG issuer could issue a high-quality sustainability bond, though we think this would be unlikely.

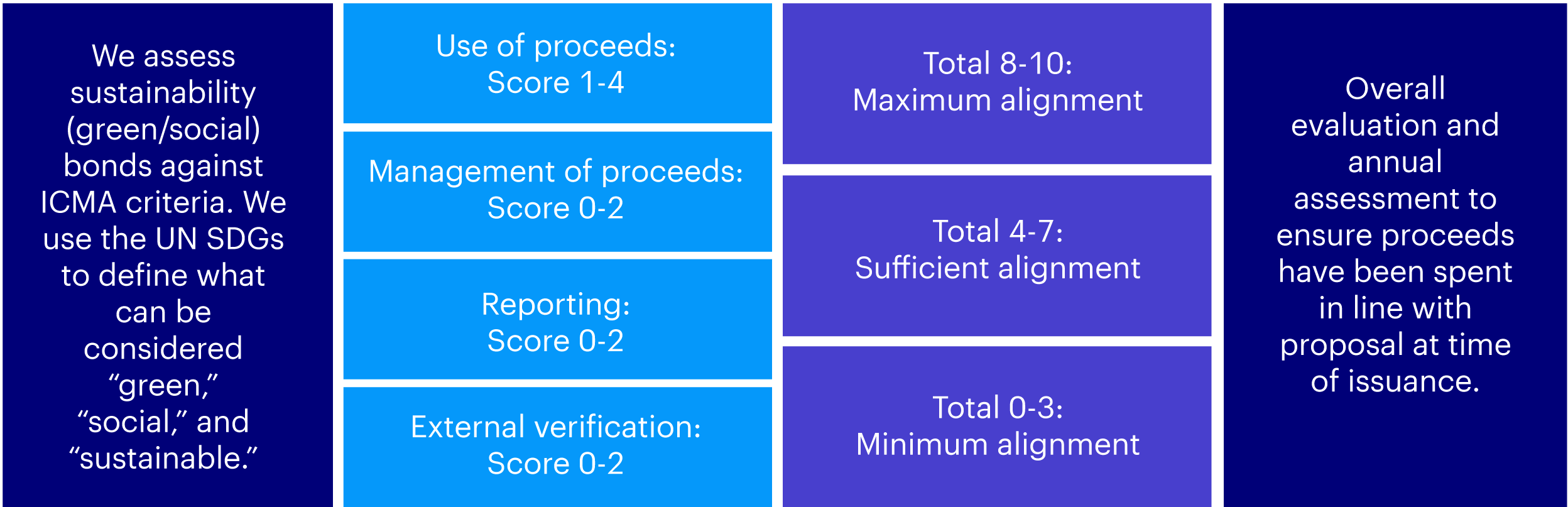

Instead, we believe it is vital to assess the issuer’s sustainability bond program. To assist with this assessment, we have developed, in collaboration with our Global ESG team, the IFI sustainability and green bond framework. This scorecard approach takes a detailed look at factors such as the use of proceeds, the management of proceeds, and reporting and external verification to assess the alignment of sustainability bonds with the UN SDGs. All else equal, we are prepared to pay more for a bond where the proceeds will be applied to projects aligned with the UN SDGs versus a “vanilla” bond. We believe the emerging “greenium” (the differential between sustainability and non-sustainability bonds from the same issuer) is a good barometer of the market’s acceptance of these instruments.3

Although we use this output to determine our investment into sustainability bonds, we believe investors generally are not appropriately differentiating between sustainability bonds with high and low alignment to UN SDGs. Indeed, we believe most investors are effectively treating sustainable bonds as homogenous. The lack of differentiation between high and low alignment is perhaps understandable, given the way bonds are typically marketed as “green” or “non-green.” But we believe failure to fully assess a company’s sustainability bond program and its ongoing compliance is a risk. Even if investors are not differentiating today, increased differentiation among sustainability bonds is likely inevitable as the market grows and matures, so we believe it makes sense to avoid “minimum alignment” bonds.

We expect further evolution to take place in 2021 in the form of an increased supply of transition and sustainability-linked bonds. These “new” bond structures pose several challenges to traditional fixed income investors and require an even more research-intensive approach, in our view. While this extra analysis is time-consuming, we find it is offset by greater opportunities for us to engage with issuers. This dynamic helps inform our active approach, which we believe is essential when investing in the labeled sustainability bond segment.

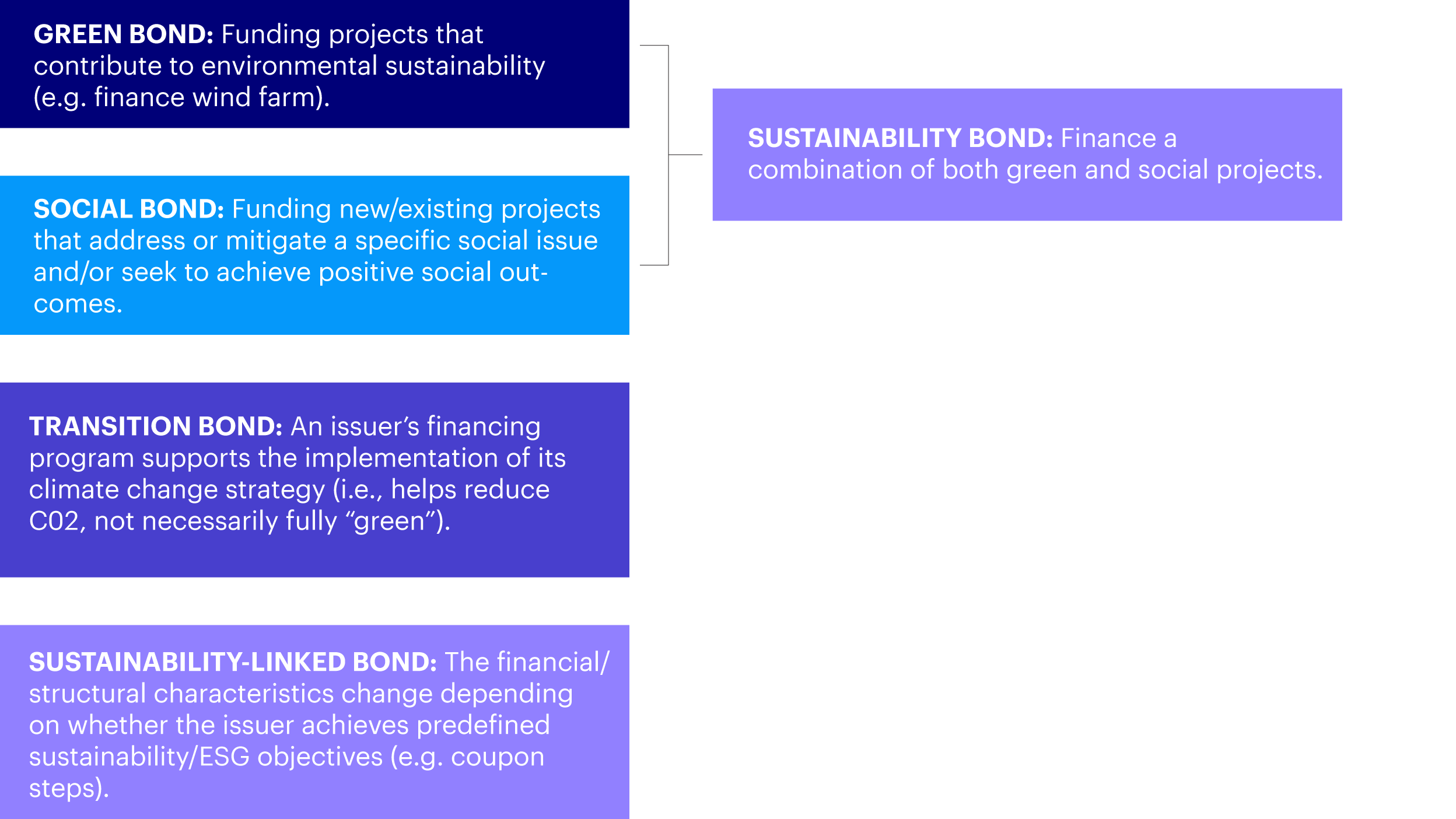

Although it is normal to see innovation in any area of financial markets experiencing growth, the pace of innovation in the sustainability bond market is notable. It is manifesting itself most obviously in the field of labeled bonds, possibly because their duration aligns well with the issuer’s expected ESG journey, but also because the low interest rate environment makes borrowing historically cheap. Nevertheless, it is interesting to see the sustainability bond market’s progression, which has evolved from the infrequent green bond in 2015 to a plethora of green, social, sustainability, transition, and sustainability-linked bonds today.

The reason we believe transition and sustainability-linked bonds require an even more research-intensive approach is because of their unique characteristics. Transition bonds (which support the implementation of a long-term climate change strategy without necessarily being “fully green”) and sustainability-linked bonds (in which bond characteristics change depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined sustainability or ESG objectives) add extra layers of qualitative and quantitative judgment, which require a detailed understanding of the issuer’s credit fundamentals and ESG credentials.

Transition bonds are complicated from an analytical perspective because they typically help finance long-term emission-reduction projects for companies operating in carbon-intensive industries. This often requires analysts to consider the issuer’s ability to execute against long-term climate change strategies (a much longer time horizon than we normally consider). Investing in known carbon-intensive industries also raises the required return of the investment, given the need to justify the addition of more carbon-intensive names to the bond universe of portfolio managers and ESG teams (which should increase as carbon emissions reporting becomes standardized). We think this may partly explain why transition bonds have been slower to be embraced by issuers and investors, despite the obvious role they could play in emissions reduction for companies unable to issue green bonds directly.

Sustainability-linked bonds contain financial or structural features dependent on the issuer’s ability to deliver a predefined sustainability objective. Often, this will take the form of a coupon step (e.g., a 25-basis point increase in the coupon) if the company fails to deliver an envisaged reduction in its environmental footprint (e.g., reduce CO2 emissions by 25% by 2025). This coupon step is effectively an embedded option in the bond. To value this option correctly, the analyst needs to fully understand the probability of the issuer achieving its sustainability objective. So, again, valuing these bonds appropriately requires an understanding of credit fundamentals but also a good assessment of the issuer’s ESG credentials and how they are likely to evolve over time. We believe the addition of a financial incentive for an issuer to achieve its target should, all things being equal, encourage compliance, but we are less convinced that the investor necessarily wants to financially benefit from an issuer’s failure to reach its ESG goal.

One silver lining for fixed income investors that has emerged from the cloud of increased complexity generated by the growth of the labeled ESG bond segment is that opportunities to engage with issuers are increasing. This is manifesting itself in meetings as companies launch sustainability bond frameworks. This includes “normal” meetings around bond issuance but also more interactive dialogue with issuers around goal setting and the use of proceeds. It remains to be seen whether issuers’ willingness to engage will persist as the labeled bond segment matures, but we believe rational management teams will be encouraged to maintain this dialogue, especially while the “greenium” exists.

Given the numerous factors in a decision to invest in sustainability bonds (fundamental credit quality, ESG credentials, assessment of the sustainability bond framework, and the likelihood of achieving ESG targets), we do not believe in a “one-size-fits-all" approach. IFI closely monitors ESG risks across our portfolios and especially in the rapidly evolving sustainability bond space. Having a well-resourced and experienced credit team is important for assessing the issues raised here and to inform our investment decisions. IFI seeks to ensure that credit spreads adequately reflect downside risks, including ESG factors, or where this is not the case, that “at-risk” names are avoided.

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations), and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Fixed income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

We are using sustainability as shorthand for green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bond issuance

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2020-09-16/eu-plans-to-sell-225-billion-euros-of-green-bonds-for-stimulus

Unfortunately, the “greenium” is not consistent and appears to be driven by several factors (deal size, issuer rating, rarity, sector etc.) rather than UN SDG alignment, which means that a more active and research-intensive approach is required to identify bonds that will potentially outperform.

Bonds had a solid start to the year with a high level of income and a diversifier for stocks. Matt Brill, Head of North American Investment Grade, explains why.

Learn how the Invesco Fixed Income team leverages active strategies to navigate risks, capitalize on credit opportunities, and deliver better outcomes.

Explore insights on front-end rate cuts, long-term yield trends, and how volatility may settle in 2025.

NA5303

This link takes you to a site not affiliated with Invesco. The site is for informational purposes only. Invesco does not guarantee nor take any responsibility for any of the content.