Uncommon truths: How will we know AI is delivering?

AI is a frequent topic of investor questions, usually concerning the price of AI related stocks. But it may also be interesting to consider how we will know it is delivering broader gains. We are watching productivity, inflation, jobs and margins.

Events of the last week in France have been instructive. The collapse of the government was accompanied by much hand wringing but also by narrowing spreads on French debt (versus German yields), outperformance of French equities (versus European counterparts) and a gradual rise in EURUSD. This all suggests that a lot of bad news was already in the price of French assets.

Meanwhile, in the US the enthusiasm that surrounded the election victory of Donald Trump seems to have faded, with US equities taking a breather versus other markets (see Figure 3) and within the US market, energy stocks and banks underperformed (though consumer discretionary and technology continued to perform well). Also, the dollar is no longer advancing, a fact reinforced by an employment report that seemed to convince markets that the Fed will ease at the upcoming policy meeting.

The implications of a second Trump term in the White House have been at the forefront of investor minds during recent 2025 Outlook meetings. Adding to the mix over the weekend was the departure of President Assad from Syria after a rapid takeover of the country by rebel forces (he was previously supported by Russia and Iran). It is not obvious how the US will react to this, either before or after the handover at the White House, especially since some of the rebel forces have previously been labelled as terrorist groups. This could complicate the geopolitics of a region that was already unstable and which, I believe, has been responsible for much of the rise in gold this year.

Those same client meetings have also revealed a lot of questions about the role of cryptocurrencies in portfolios, which is not surprising given the post-election rally. However, very revealing was a client question for the rest of the audience in London, that showed that none of the participants held such assets on behalf of their clients, suggesting they are an interesting talking point but not yet considered viable for client portfolios. Personally, I cannot include them in my asset allocation framework due to a lack of historical data over numerous cycles and, more importantly, a lack of any framework that would allow me to forecast returns.

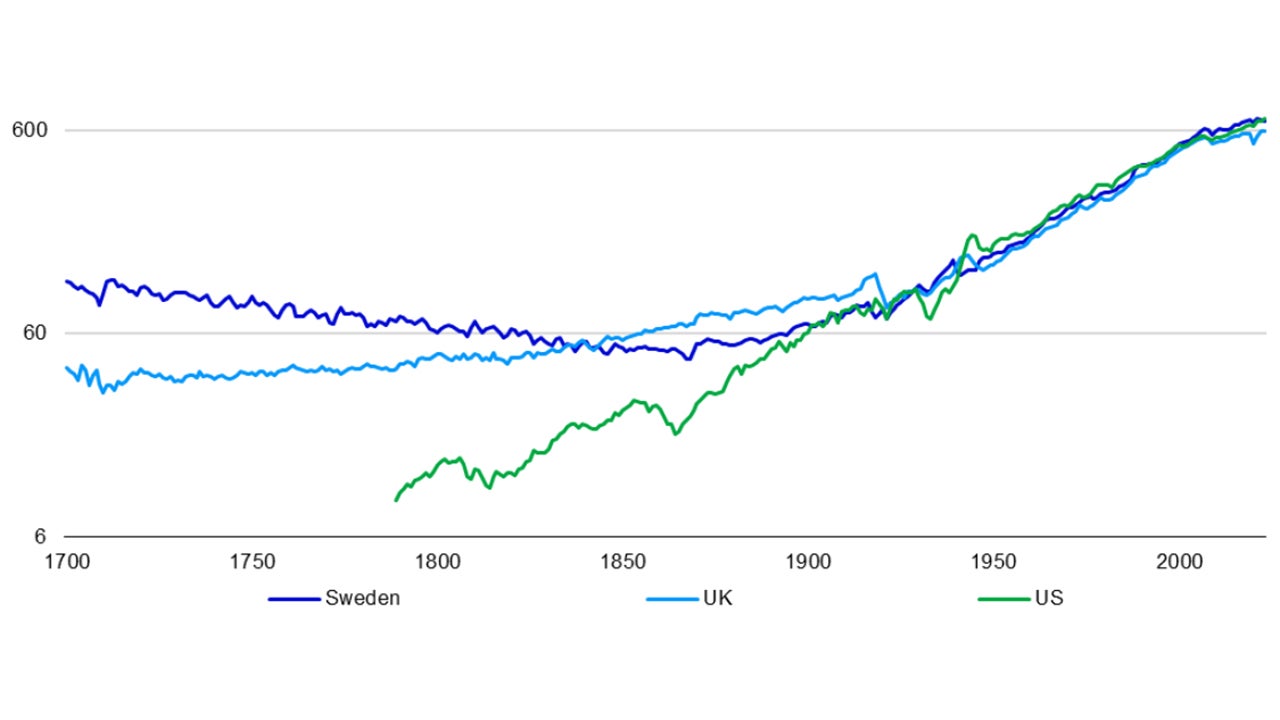

More interesting, I believe, is the flow of questions about artificial intelligence (AI). These are usually aimed at understanding whether the extreme concentration in the US market in AI related stocks can continue? I believe it would be foolish to say it couldn’t but history suggests that such concentration peaks don’t last forever. Ironically, perhaps one factor that could reduce the concentration in AI enablers could be a broadening of the benefits of AI to the rest of stock market. I think this would require AI to prove its worth as a boon to productivity, which, judging by the flattening of GDP per capita in recent decades (see Figure 1), would be welcome. So, what would we need to see to believe AI was bringing such benefits?

Note: Annual data from 1700 to 2023, based on GDP in local currency. Population data is interpolated in early periods when not available annually. Source: Global Financial Data and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

The obvious answer is an upturn in productivity, with each worker becoming more efficient. However, productivity is cyclical, with a tendency to fall during recessions and rise during upswings, as output reacts faster than employment. Hence, it may be difficult to disentangle short term cyclical effects from more fundamental shifts.

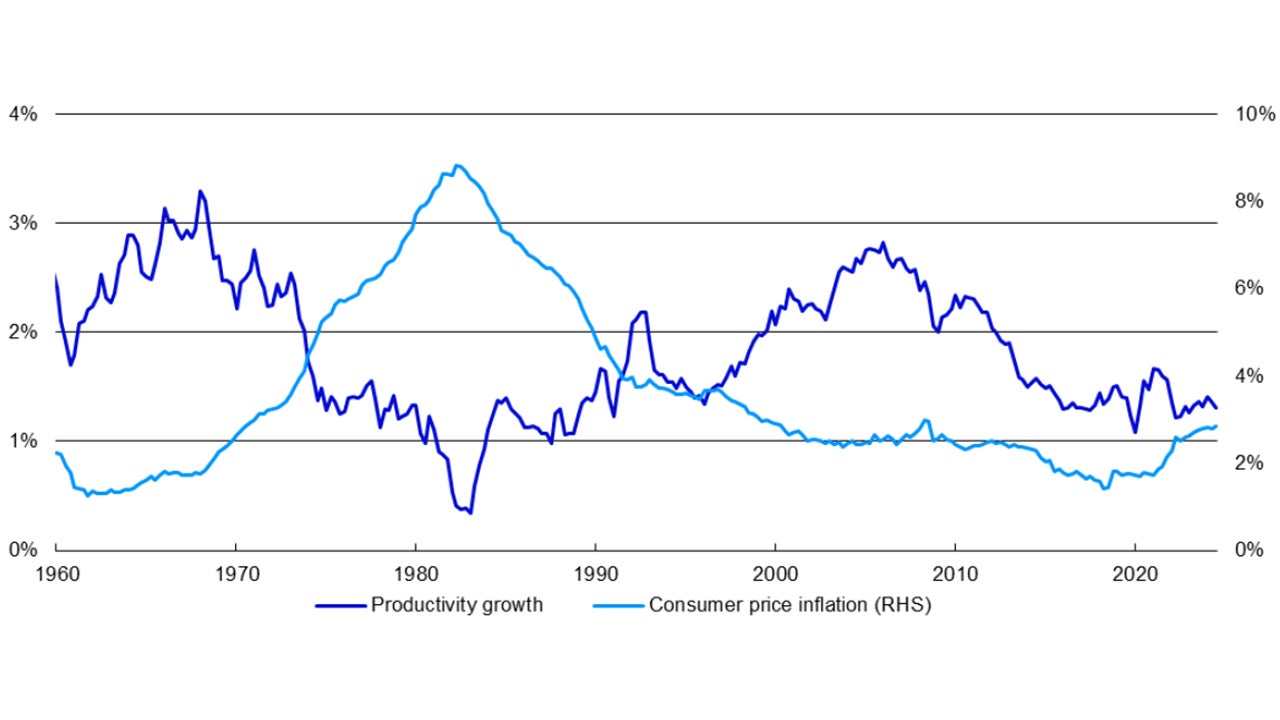

Figure 2 shows annualised 10-year changes in productivity to minimise short term cyclical influences. There are some clear swings over the period since 1960 and it would be nice to think they reflect underlying changes in productivity but I suspect the downdraft after the early 1970s was related to the deep recessions that followed the oil price hikes of 1973 and 1979. Likewise, the climb in productivity throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s may have simply reflected the long recovery after those recessions.

However, it is tempting to also conclude that the rise in productivity after the mid-1990s was in part caused by the roll out and adoption of technology (software, world wide web, email, internet, mobile phones, laptops etc.). Importantly, those gains in productivity and long economic upswings were not accompanied by higher inflation, despite the rise in commodity prices in the first decade of this century. And that brings us onto what could be another sign that AI is delivering broader benefits: falling (or stable) inflation, while economies are accelerating.

Of course, there could also be a negative sign, that by definition goes with productivity gains, that of job losses and rising unemployment. If AI really is a labour saving tool, then job losses are likely to follow. Indeed, it is hard to think of too many spheres in which jobs would not be lost. Hence, we should be on the lookout for confusing employment reports with job gains not matching the growth of the economy. At best, under such a scenario job gains would be disappointing in upswings (prepare for jobless recoveries) and at worst recessionary job losses would be accentuated.

Finally, that brings us to the equity market interest. Economy wide productivity gains should boost profit margins and accelerate profit growth, in my opinion. As for the bond market, the outcome may not be obvious. If lower inflation is the outcome, then yields may fall, but if trend growth is raised, the effect could be to raise real yields. I suspect there will be a bit of both, with nominal yields rising a bit. Then, the effect on general equity prices may not be so positive, if the higher future profits are discounted at a higher rate. In any case, I suspect the broadening of the benefits to the wider economy would see a reduced value placed upon AI enablers, as we would then be able to access the AI theme in a number of different ways and at more reasonable prices.

So, I think we should keep an eye on trends in productivity, employment, inflation and profit margins but it may be hard to separate the underlying wheat from the cyclical chaff. Figure 1 shows that even at the time of the industrial revolution, the effect on GDP per capita was not immediately obvious in Sweden and the UK (the US benefitted from a process of catch up). The effects of AI may be too subtle to overcome cyclical effects and it may require a lot of hindsight to identify the moment of take-off.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 6 December 2024.

Note: Quarterly data from 1960 Q1 to 2024 Q3. Productivity growth is based on real output per worker in the non-farm business sector. Source: Global Financial Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office