Uncommon truths: Elections and Fed rate cuts: the perfect recipe?

We are witnessing a rarity: the Fed initiating an easing cycle within two months of an election. Could this be the perfect recipe for risk assets? Elections have tended to be followed by strong credit and equity performance but the evidence on Fed easing is mixed. If the mid-1990s were a good template, the portents would be good but I worry about slow growth, valuations and politics.

At the halfway point of a tour of Asia, US elections remain a topic of keen interest. At meetings so far, it is my impression that a small majority of investors think Donald Trump will be the next president. Broader media commentaries seem to suggest that US stock markets and the dollar are rallying in that belief. So, what does history tell us about the effect of elections on US asset performance and how does this compare to what usually happens when the Fed eases?

First, it is worth noting that we are witnessing something that is almost unique in the last 100 years: a Fed easing cycle starting within two months of a presidential election (which traditionally take place on the first Tuesday of November). Other examples were the election of 2000, with the Fed starting to ease on 2 January 2001 (not a great precedent for stock investors), 1984, with the Fed starting to ease on 30 August (almost within two months of the 6 November election) and, if we really stretch things, 1968, when, in the middle of a tightening cycle, there was a single rate cut on 30 August that was reversed by year-end.

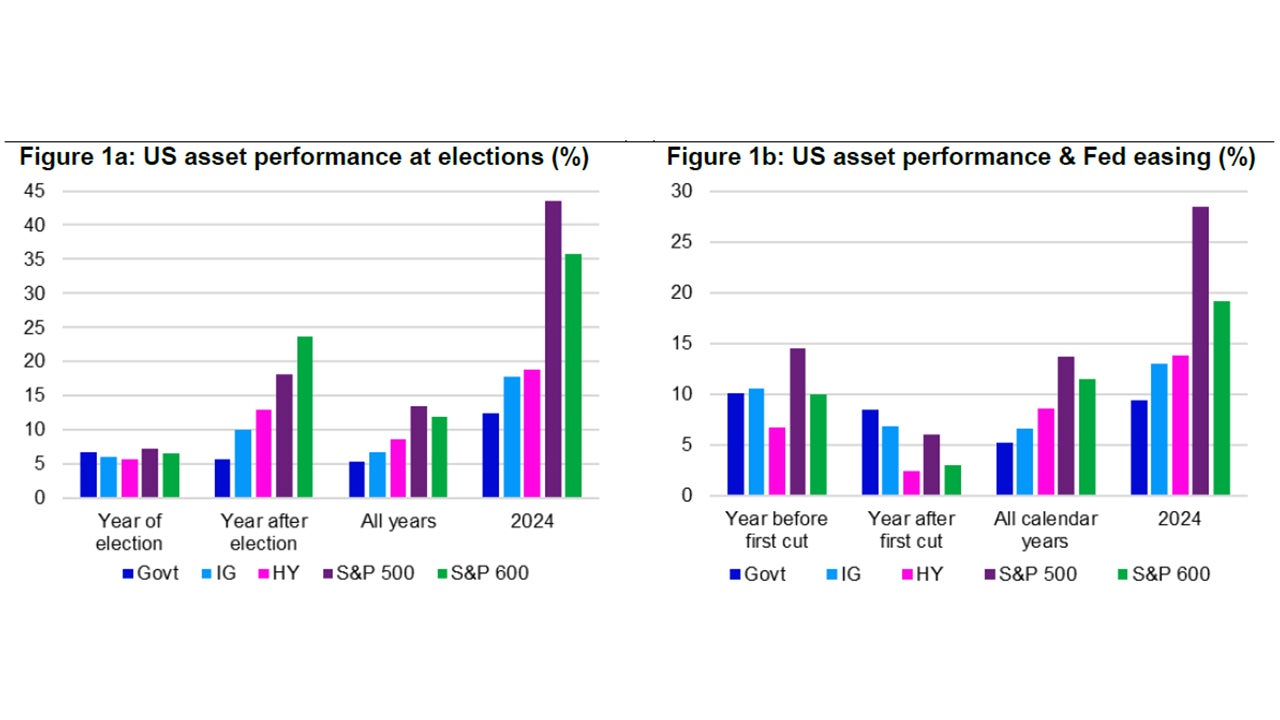

As far as elections go, history is encouraging for credit and stock investors. Figure 1a shows average US asset performance around US presidential elections since 1988 (a start date chosen because the high yield (HY) index only started in 1986). It appears that most assets have on average done better in the year after elections than in year before (year-ends are defined as 31 October to better match the election cycle). Performance in the year after elections has also tended to be better than the average across all years since 1988. Government bonds appear to be the exception, with little difference between pre-election, post-election and average annual performance.

Turning to Fed easing cycles, Figure 1b is less promising, with returns on all assets tending to be worse after the first rate cut (a lot may already be priced in). Also, defensive assets (government bonds and investment grade (IG)) have tended to outperform the riskier assets after the first cut (the latter perhaps hit by recession). Those defensive assets have also tended to perform better than average (“All calendar years”) in the year after the first rate cut, while riskier assets have not. Again, given the limited history of the HY index, the analysis cannot start earlier than 1986, with the first easing cycle included in this analysis starting in June 1989 (see the appendix for the dates of the first rate cuts). This limits the analysis to five rate cutting cycles prior to this year (the focus is on rate cuts, rather than quantitative easing), which is not an enormous sample (nine elections are covered).

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The charts show total returns in US dollars. “Govt” is based on the ICE BofA US Treasury Index; “IG” is based on the ICE BofA US Corporate Index and “HY” is based on the ICE BofA US High Yield Index. Figure 1a is based on monthly data from 31 October 1987 to 30 September 2024 and shows average returns in presidential election years since 1988 (with years defined as running from 31 October in the preceding year to 31 October of the election year), compared to the returns in the year after the election (defined as being from 31 October in the election year to 31 October in the following year). “All years” shows the average return across all years since 1988 (with years running from 31 October, starting on 31 October 1987). “2024” shows the annualised return from 31 October 2023 to 30 September 2024. Figure 1b is based on daily data from 1 June 1988 to 18 September 2024 and shows average returns in the years before and the years after the day before the first interest rate cut in Fed easing cycles (the focus is on interest rates and not quantitative easing). “All calendar years” shows the average return across all calendar years from 1988 to 2024 (the latter is the annualised return up to 30 September 2024). “2024” shows the returns in the year before the 18 September 2024 Fed rate cut. See appendices for charts that exclude the global financial crisis and pandemic episodes and for dates of the first interest rate cut in Fed easing cycles.

Source: ICE BofA, S&P Dow Jones Indices, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Of course, the circumstances of each election and easing cycle are different and those averages may hide more than they reveal, especially when it is considered that they include the global financial crisis (GFC) and the Covid pandemic. The appendix contains charts that show what happens if we exclude those two extreme episodes. A comparison of Figures 1 and 8, suggests that the GFC and pandemic episodes had a number of effects on the data in Figure 1: first, all pre-election asset returns (except government bonds) were depressed due to large losses in 2008; second, post-election credit (IG and HY) and equity returns were boosted by the large rebounds in 2009 and 2021; third, pre-rate cut small-cap equity returns were reduced by the poor performance prior to the July 2019 easing and, finally, post-rate cut credit and equity performance was depressed by large negative returns in the year after September 2007 rate cut (as the GFC was unfolding).

Hopefully, neither the GFC nor pandemic episodes will serve as guides for the coming year. A more encouraging template may be the mid-1990s, a period during which the Fed eased from rates similar to those of this cycle (starting on 5 July 1995), an election occurred (5 November 1996) and there was no recession (according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, there was no recession between March 1991 and March 2001).

All asset returns were impressive in 1995, with further strong gains in 1996 and 1997 (especially for HY and equities). Hence, there were strong returns for all assets in the year to the first rate cut in July 1995 and equities delivered similar high returns in the following 12 months. Likewise, strong returns across all assets in the year to the November 1996 election became even stronger in the year after.

So, what could go wrong and prevent mid-1990s like HY and stock returns? The obvious answer is disappointing growth or even recession. It is worth noting that average quarterly annualised GDP growth was 3.8% in the 1994-97 period, versus only 2.3% since the start of 2022.

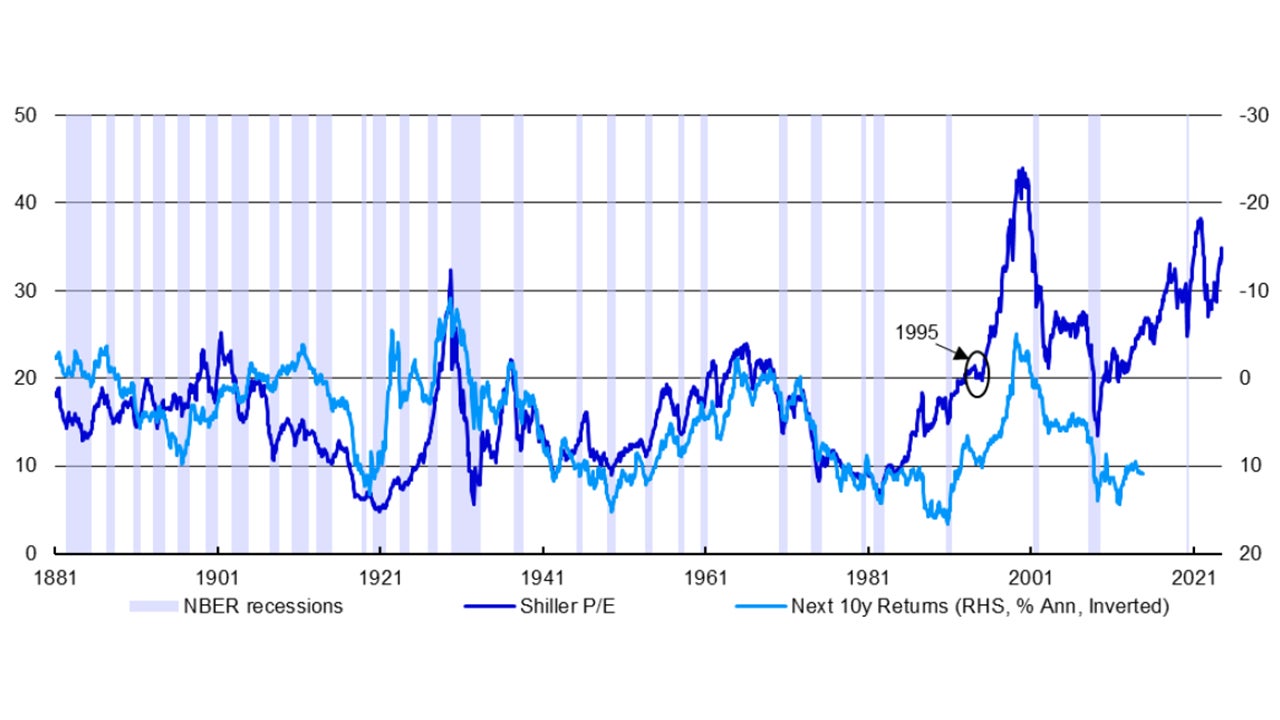

Also, Figures 1a and 1b show that all assets (especially equities) have performed extremely well in the last year. This is now reflected in HY spreads that are close to cyclical tights and elevated broad equity index valuations. Figure 2 shows that equity market valuations (as judged by the Shiller PE) bear no relation to those in 1995 (the Shiller PE started that year at around 20 and is now around 35). It can always go higher (it peaked around 43 during the dot.com bubble) but the starting point seems to have priced in a lot of good news. Also, US market concentration is much higher than during that previous tech bubble.

Finally, the election itself could bring bad news. Though markets seem to be embracing the idea of a Trump presidency, I am not convinced that he will win, nor that, if he does, an economy weakening boost to tariffs, a tax cut fuelled deepening of fiscal imbalances and an undermining of the Fed’s independence will bring a strong dollar or a record breaking stock market. I am currently underweighted in the US equity market within my Model Asset Allocation (see Figure 6) and suspect the dollar will weaken. I favour an equally-weighted approach to US stocks.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 18 October 2024.

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Monthly data from January 1881 to September 2024 (as of 30 September 2024). “NBER recessions” are periods of US recession, as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. See appendices for definitions and disclaimers. Source: Robert Shiller, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office