Applied philosophy: Strategist from East of the Elbe – Q2 2025

The total returns on assets in Central and Eastern EU member countries (CEE11) have been mostly strong within equities and have been subdued in government bonds in the last four months. Inflation has picked up in most economies, and interest rate expectations rose at the same time as global economic growth seemed to have remained sluggish, while policy uncertainty rose in the US. We expect growth to reaccelerate in 2025 both within and outside the region and move towards trend, and we expect inflation to stay above central bank targets. In my view, this outlook should support both government bonds and equities in our CEE11 universe.

Spring seems to have sprung even in London, where the climate has the cheeky habit of flaunting some pleasant weather in early-March just to cruelly take it away as a cold snap replaces warming sunshine. We can only hope spring will return to global equity markets after the recent pull-back. However, I think that partly depends on improving visibility for both US policymaking and the future path of the global economy.

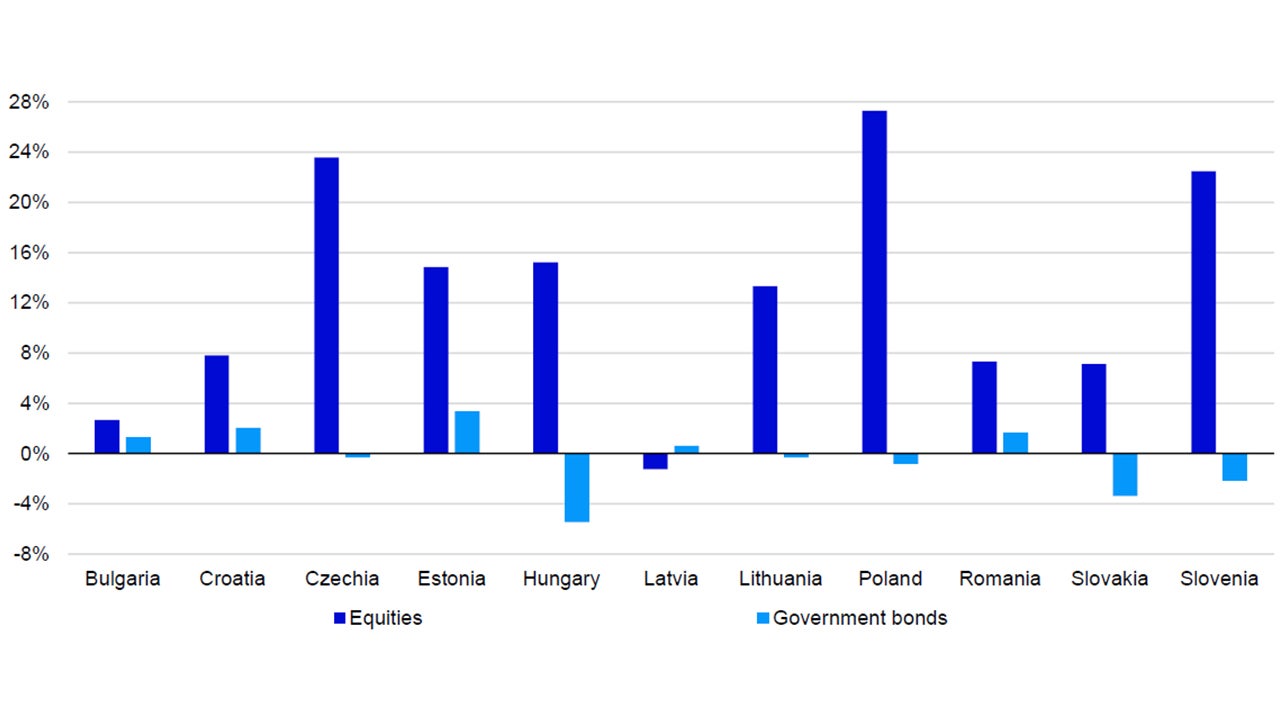

Equity returns since the end of November in the CEE11 countries within our universe have been mostly strong (apart from Bulgaria and Latvia), though government bond returns were more subdued. Within equities, we highlighted Slovenia and Poland as our most preferred markets in our last edition, while we thought Bulgaria and Hungary were likely to underperform (see here for the full detail). As shown in Figure 1, Poland was the best performer with Slovenia not far behind. At the same time, while returns for Hungary were much stronger than we expected, Bulgaria was the second worst performer.

Government bond returns remained subdued for most countries and were negative for six countries, partly driven by an uptick in inflation. We chose Romania and Poland as our most preferred in our last edition. Although Romania was among the stronger performers, Poland had negative returns (Estonia had the strongest returns between 30 November and 28 March 2025). On the other hand, we highlighted Croatia and Slovenia as our least preferred. While Croatia was the second best performer, Slovenia’s returns were negative.

Government bond yields rose in most countries due to a mix of stubbornly sticky inflation and expectations of higher government spending following Germany’s revision of its “debt brake” policy. Apart from Czechia, Estonia and Lithuania, fiscal deficits may remain elevated partly due to higher spending on interest payments. Yields have remained high in Romania due to ongoing uncertainty around the presidential elections, in my opinion, which will be repeated in May 2025. However, the largest rise in yields (99 basis points between 30 November 2024 and 28 March 2025) happened in Hungary, where the government is planning to increase social spending ahead of elections in 2026.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 28 March 2025. We use Datastream Total Market indices for equity returns. Government bond returns for Czechia, Hungary and Poland are based on Datastream 10-year benchmark government bond indices. We create a monthly index of government bond returns for all other countries by calculating the net present value of coupon payments and capital repayment based on redemption yields.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

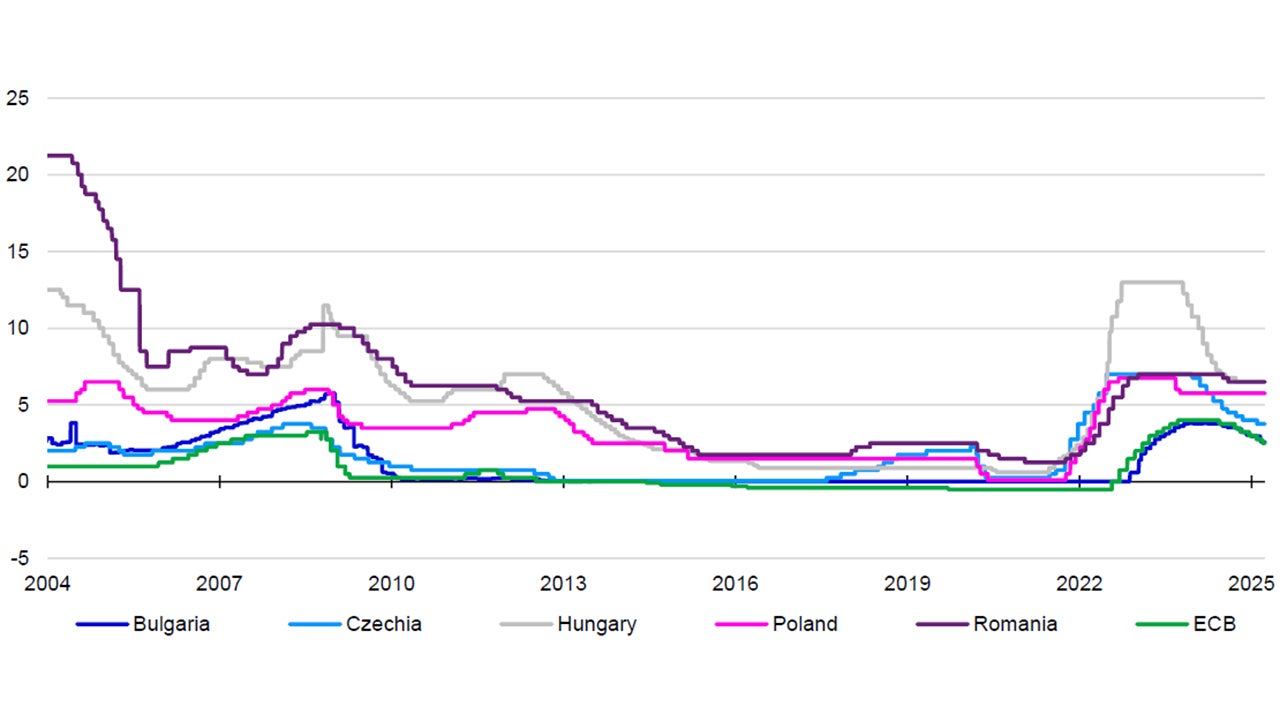

We expect Developed Market (DM) central banks to continue easing monetary policy, but we think that the process will be gradual as rate setters remain mindful of upside risks to inflation, especially if the rise in tariffs becomes widespread. I think CEE11 countries are highly exposed to disruptions in global trade, especially those outside the euro area, where currency movements can become volatile if investor sentiment sours. As Figure 2 shows, the Hungarian, Polish and Romanian central banks have all left their rates unchanged since autumn 2024, while the Czech National Bank (CNB) proceeded with gradual rate cuts alongside the European Central Bank (ECB), although rate futures indicate that both may be close to reaching the end of this monetary easing cycle.

In our view, the global economy could reaccelerate in 2025 after going through a phase of weak growth, thus rapid rate cuts may increasingly seem inappropriate. In CEE11, GDP growth in Q4 2024 diverged, although remained positive (except for Latvia). I expect the laggards, especially those that are highly exposed to the slowdown in the German economy (for example, Hungary and Slovakia) to catch up to the better performers, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania and Poland, especially if prospects for economic growth improve in the Euro Area. That probably implies no significant decline in inflation, and therefore interest rates may remain near current levels, in my view.

I think a lot will also depend on how long policy uncertainty remains and how much that impacts economic growth especially in the short term. It would not surprise me if central banks adopted a wait-and-see approach and would lean towards holding rates at current levels, while monitoring economic indicators.

The political landscape, on the other hand, is likely to be stable in the next 12 months despite turbulence in Romania as we await the repeated presidential election. Markets also seem to have been unaffected by the Polish presidential election of May 2025, even though the current president, Andrzej Duda, is ineligible for re-election. In my view, the Czech parliamentary elections, which will be held in the autumn of 2025, is too far ahead to appear on the markets’ radar.

I think the global macroeconomic backdrop will be supportive of regional assets in general. In our latest The Big Picture, we reiterated the view that the prospects for growth may improve during 2025, although there is more uncertainty around the future path of inflation. Accordingly, we cautiously increased our allocation to risk assets (despite rich valuations in some cases), and we maintained our preference for Emerging Markets as a whole.

In CEE11 countries, I think growth will stay higher than in DM assuming decent real wage growth and no need for monetary tightening in response to higher inflation or currency weakness. In my view, fiscal policy is likely to be expansionary or neutral in most countries, although spending may be constrained somewhat by higher debt servicing costs.

What does this imply for markets? The main question, in my view, is how far and how quickly growth reaccelerates after getting through a potential soft patch, assuming the global economy avoids a deep recession the probability of which has increased recently. I think that markets may start pricing in stronger growth only if US policy uncertainty decreases, potentially boosting risk assets, although we may see some weakness and volatility in the near term.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 28 March 2025. Using daily data from 1 January 2004. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

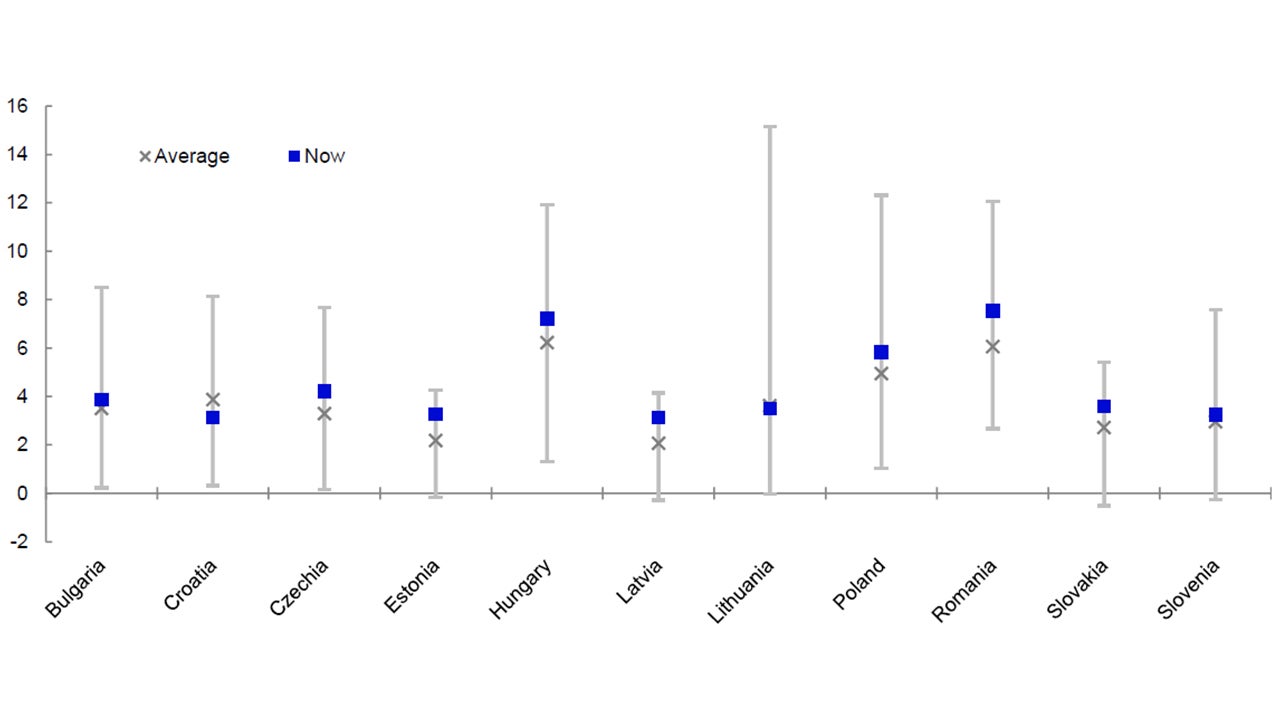

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Data as of 28 March 2025. Historical ranges and averages include daily data from 14 April 2006 for Bulgaria, 30 January 2008 for Croatia, 1 May 2000 for Czechia, 1 February 1999 for Hungary, 15 April 2003 for Lithuania, 1 January 2001 for Poland, 16 August 2007 for Romania, 7 January 2004 for Slovakia, 3 April 2007 for Slovenia and 24 November 2020 for Estonia and Latvia. We use Refinitiv Government Benchmark 10-year bond indices for Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. We use Datastream benchmark 10-year government bond indices for Czechia, Hungary and Poland. We use OECD 10-year government bond yields for Estonia and Latvia as of 28 February 2025.

Source: LSEG Datastream, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

A risk-off environment in the near term could mean that until we get more clarity on the outlook for growth (especially for the Euro Area) CEE11 assets may underperform EM and Global benchmarks. However, on a 12-month view, I think the economic environment could be favourable for both equities and government bonds within CEE11 (we consider them risk assets within a global asset allocation context).

For those markets outside the Euro Area, currencies may also play a major part in determining returns, especially within equities, where weakness may contribute to higher profits (up to a point). However, I think the probability of further weakening in 2025 is limited especially against the US dollar, assuming that interest rates behave as expected by futures markets and consensus.

Regional currencies strengthened against the euro in the last four months, which is not surprising given the divergence of monetary policy in Hungary and Poland. Czech rate expectations have also been repriced, although monetary policy easing has continued for now. I expect limited rate cuts from both major DM and local central banks, which are likely to proceed at a similar pace, thus we may be close to the end of the widening in rate spreads. Rate futures and Reuters consensus forecasts indicate rate cuts of at least 100bps for Poland, around 50bps for Czechia and Romania and 25bps for Hungary compared to about 50bps for the ECB and just under 75bps for the Fed until the end of 2025 (as of 28 March 2025). Thus, apart from the PLN which could weaken in the next 12 months, I expect moderate movements in exchange rates versus both the euro and the US dollar, unless there is a sudden deterioration of economic momentum (either within the region or globally).

I believe the biggest risk to regional returns remains a deep global economic slowdown, which could trigger a “flight to safety”. The probability of such an event has increased, driven by higher policy uncertainty in the US. A further increase in tariffs against European economies – especially Germany – may also have an indirect impact on these economies as they are embedded in the supply chains of a number of large companies within developed Europe.

In absolute terms, the 10-year yields of Romania and Hungary at 7.5% and 7.2% respectively are the highest, which is not surprising given that they also have the highest central bank rates within the region (as of 28 March 2025 – see Figure 3). In general, I would expect CEE11 yields to be lower than the 6.9% yield on the broader EM universe (Figure 6 – based on the Bloomberg Aggregate Sovereign Bond Index in USD as of 28 March 2025) due to their structurally lower inflation and interest rate expectations.

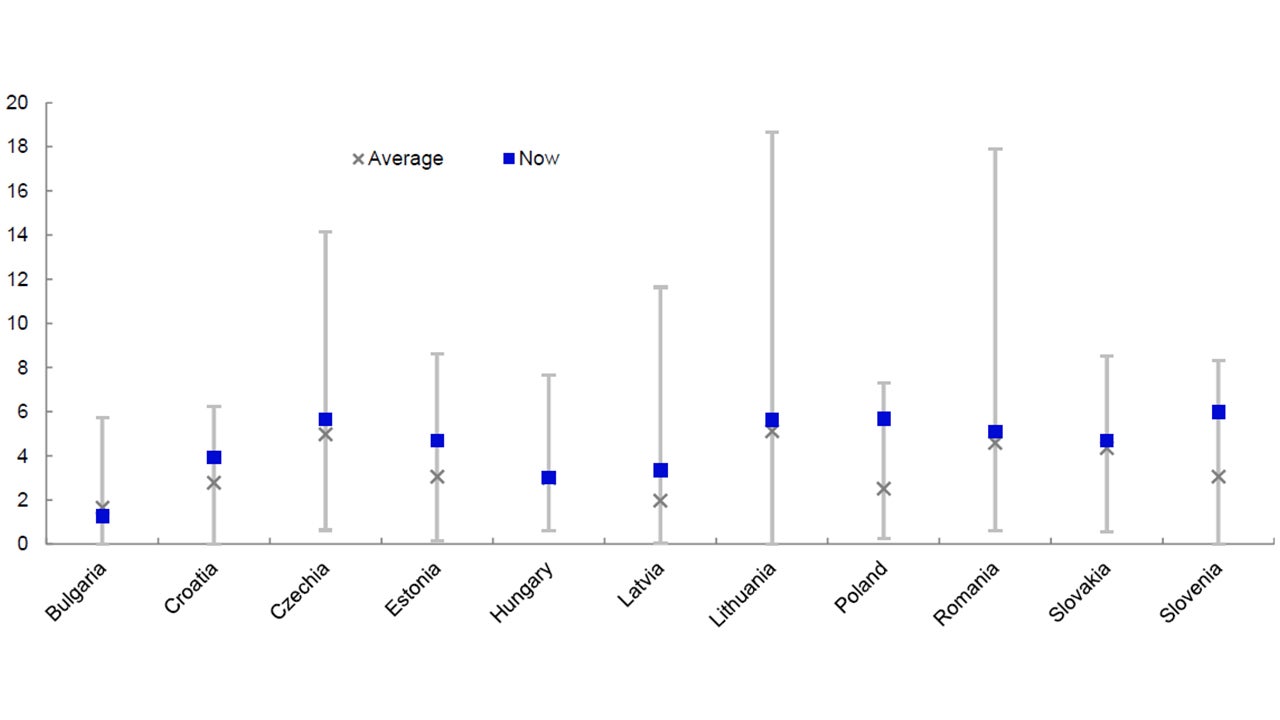

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Data as of 28 March 2025. Based on daily data using Datastream Total Market indices. Historical ranges and averages include daily data from 2 October 2000 for Bulgaria, 3 October 2005 for Croatia, 27 January 1994 for Czechia, 5 June 1997 for Estonia, 21 June 1991 for Hungary, 3 November 1997 for Latvia, 1 April 1998 for Lithuania, 1 March 1994 for Poland, 29 December 1997 for Romania, 1 March 2006 for Slovakia and 31 December 1998 for Slovenia.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

The political turbulence in Romania may have temporarily pushed yields higher, which could present an opportunity assuming they normalise in the next 12 months. However, in Hungary’s case, plans for fiscal loosening may not leave much room for strong returns, especially if interest rates remain higher than in the rest of the region. On the other hand, I think Poland has more potential for outperformance, especially if rate cuts start earlier than mid-2025. Polish government bonds have the third highest yield in the region at 5.8% (see Figure 3) and their spreads vs German bunds are also higher than historical norms. At the same time, Croatian and Lithuanian bonds seem to have the least attractive valuations with yields and spreads versus Bunds below historical averages.

Despite the increasingly uncertain economic outlook in the short term, I expect healthy equity returns in the region based on our assumption of a global economic recovery in 2025. While there may be a few bumps on the road in the near term, valuations look favourable in most markets within the CEE11. Apart from Bulgaria and Hungary, they also offer higher yields in absolute terms than the 3.3% of the broader EM universe (using Datastream Total Market indices as of 28 March 2025). In my view, Slovenia and Poland continue to be in the sweet spot of having a dividend yield well-above historical norms and relative to their peers in the region (see Figure 4) despite over 20% returns year-to-date. Polish dividend yields are also significantly higher than historical averages and the market has lower levels of concentration than other markets, while it provides exposure to cyclical sectors, which may outperform if economic growth picks up. At the same time, I still view Czechia as an attractive hedge against potential market volatility in the near term with its dominance by the country’s largest utility company.

On the other hand, I cannot overlook the low yields on offer on Bulgarian equities, which are also the only ones below their historical averages. At the same time, both the dividend yield and the yield premium compared to historical norms is now the second lowest within the region for Hungary, thus I view these markets as having the least potential for outperformance.

Figure 5 – Our most favoured and least favoured markets in Central and Eastern Europe

| Government bonds | Equities | |

| Most favoured | Romania, Poland | Slovenia, Poland |

| Least favoured | Croatia, Lithuania | Bulgaria, Hungary |

Source: Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.