Global equities series: Foreign economic policies, trade deficits and trade barriers

This is the sixth of an eight-part series that covers the themes and challenges facing global equities in the second Trump administration. Part 1 covers the impact of an America-first world order while Part 2 looks at Trumpism's issues. In Part 3 we delve into immigration, the Federal workforce and US labor markets. Part 4 unpacks deregulation, oil demand and inflation pressures. Part 5 covers the US fiscal policy, debt and deficit and Part 6 looks at foreign economic policies and trade concerns. In Part 7 we deep dive into geopolitics and geoeconomics and Part 8 unpacks portfolio diversification in America-first global equity markets.

We expect team Trump to follow a long tradition of US economic and financial statecraft with current geopolitical and technological twists. Large US trade deficits and the sharp deterioration in the US net international investment position are becoming major geoeconomic issues with geopolitical overtones. We believe Trump will use tariffs as leverage to increase market access and cooperation on defense funding, immigration restrictions and the war on drugs and fentanyl when it comes to allies, partners and friends but will aim to reduce US reliance on China.

Protectionism may be Trump’s longest, most deeply held policy conviction: In 1986, he placed a full-page NY Times ad calling for tariffs against Japan. Plans to tariff allies and adversaries alike have raised fears of inflation or stagflation via both final goods and supply chains; worries about effects on corporate pricing power and productivity and other plans to boost investment, sustain consumer purchasing power and cut taxes all point to stronger domestic demand and hence wider trade and current account deficits. How these contradictions are resolved, or at least how trade-offs are managed, could make a major difference across asset classes and economies.

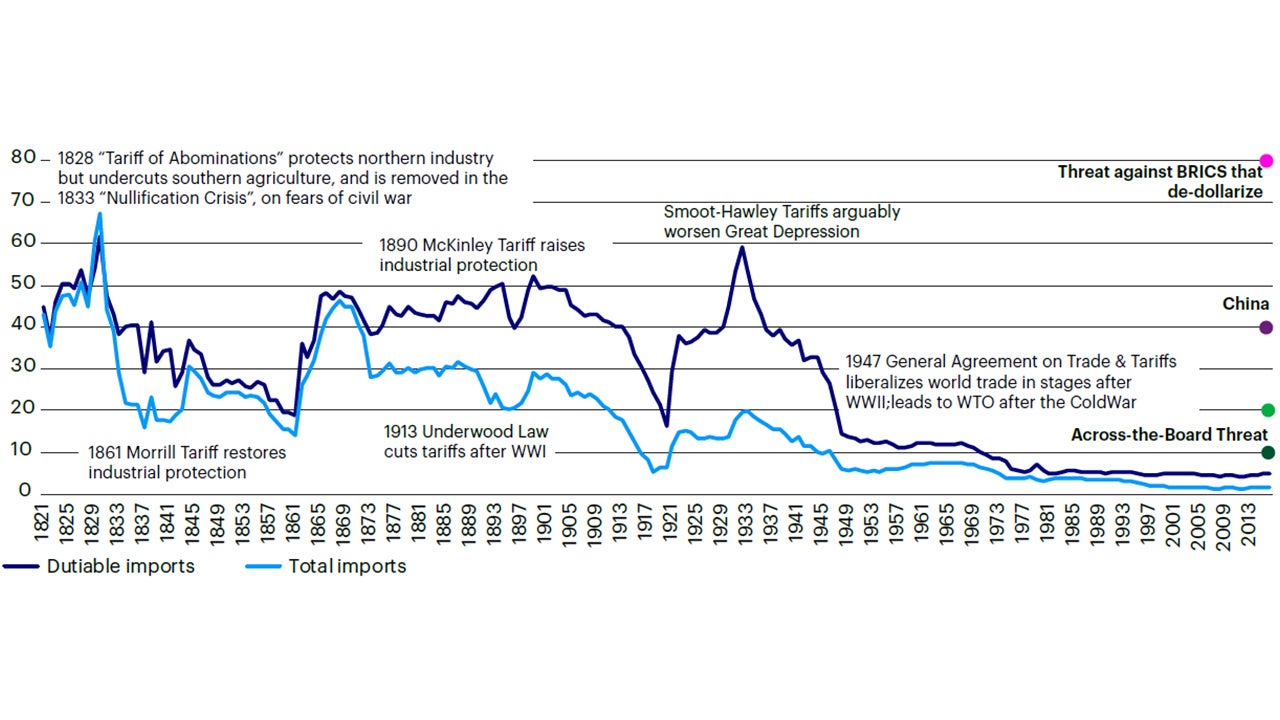

Trump’s tariff threats in historical context: US average tariffs were among the lowest of major economies and the lowest in US history before Trump’s first term. Even now, many specific tariffs have been raised, yet overall, tariffs are below historical highs. Trump’s threats to raise across- the-board tariffs for all trading partners, and sharply for China, in particular, would likely still leave overall tariff levels below those in the most protectionist episodes in US history.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Database, St. Louis Fed, Invesco. Annual data to 2016, latest available as at 6 December 2024

Tariffs and Inflation? We doubt that tariff hikes by themselves will have much direct inflation effect. Raising tariffs without reducing trade with quotas or outright regulatory bans (e.g., as with sensitive, “dual-use” or “civ-mil” items) would raise the price of tariffed goods relative to substitutes or other goods. Plus, the dollar would rise against currencies of tariffed trade partners. All these shifts would reduce the impact of tariffs on inflation, especially if the tariffs were imposed all at once or in a few steps, as seems to have happened with tariffs in Trump’s first term.

A more conventional inflation risk could rise if tariffs were ratcheted up periodically, affecting both the supply side and final goods, especially if demand were running strong, and more so if other policies were expansionary (e.g., deregulation or unfunded tax cuts). We would expect the Fed to hold monetary policy tighter than otherwise in such a scenario but look through the effect of one-off tariff hikes as a price-level effect, as some Fed officials have indicated.

Protectionism and productivity: “American exceptionalism” poised to persist? Originally used to convey the idea of a unique society founded on ideals of equality and freedom (especially of expression and enterprise, not nationality or religion), US exceptionalism has come to connote economic and financial market outperformance. These two concepts are arguably complementary: The US is the one major economy to reach and redefine the technological frontier with highly profitable corporates even in long periods of heavy protectionism, we think due to uniquely intense domestic competition despite protection against foreign competition. Trump aims in our view to restore this vision of dynamic US capitalism behind high trade barriers, rejecting Bidenomics by abandoning industrial policy and subsidies in favor of deregulation.

Today, China may be pursuing similar ideas with great success in high-tech manufacturing, India in cutting-edge services. China relied on industrial policy throughout its rapid catch-up, most recently in picking favored sectors like solar power, EVs, semiconductors and high-tech in general, as well as subsidizing start-up firms. But beyond that, it has also generated fierce competition in so-called sandboxes. Most other major economies have relied on competition in global markets for technological, managerial and process innovation and competitiveness. India for its part tightly regulated industry but was hands off on services, particularly in new technology and business service sectors, such as software, business process outsourcing and more recently, medical tourism and AI and other new generation programming – all sectors that have taken off. In stark contrast, most historical European and emerging market performance with protectionism and industrial policies has been poor. Pending major changes, including deregulation and a more generally supportive environment for investment and employment, and for new sectors in Europe and EMs beyond China and India, we would expect investors to remain skeptical of macro and corporate performance prospects despite attractive valuations, vs. the US (and perhaps India).

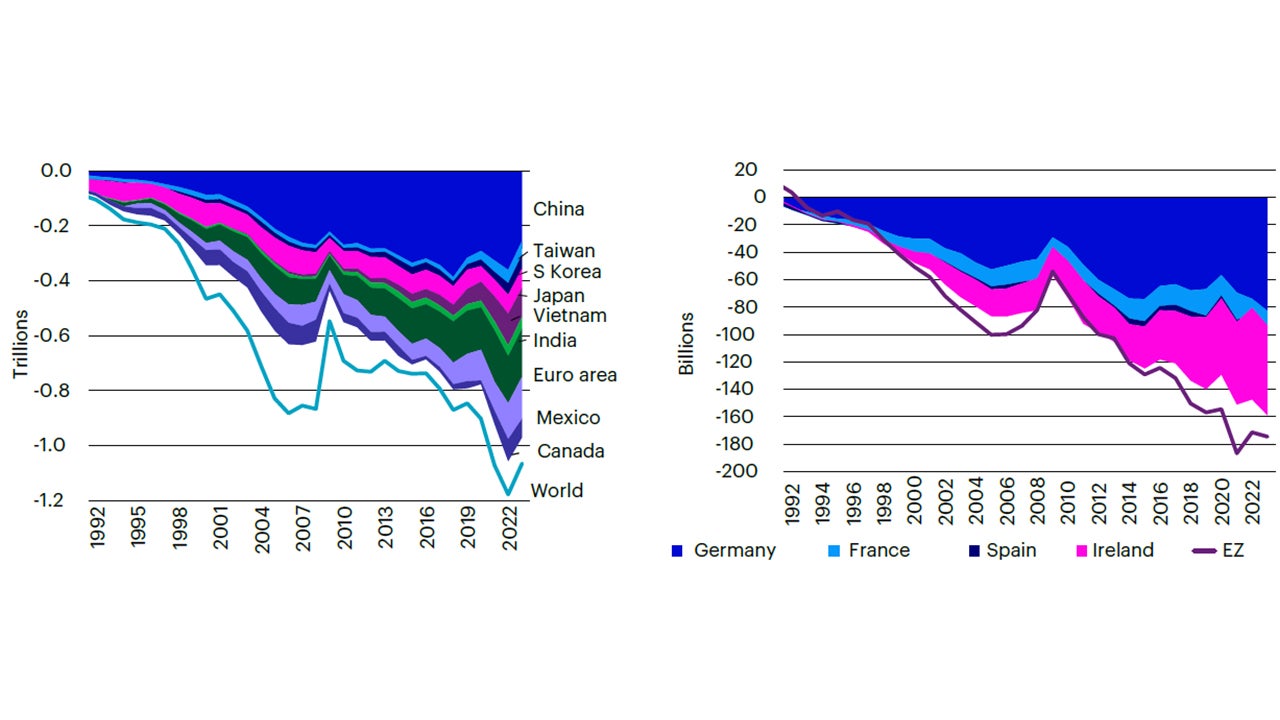

US Trade grievances: The US is by far the world’s largest continuous deficit country. Some others also run trade deficits continuously – the UK, India, Brazil, Turkey, Australia, etc. But these economies or their deficits are relatively small. On the flip side of the coin are several continuous surplus countries, including the EZ, Japan, China, South Korea, Russia and others – all split across US allies and partners, and adversaries. Team Trump argues that contrary to standard economic and market views, these deficits reflect unfair trade: The US is much more open to exports than trading partners’ markets are to US exports. Thus, the US has no chance of moving to balanced trade in line with the original theories of free trade, in which both trading partners become better off by exchanging goods or services with each other, and as a result the US is confined to exporting commodities and exchanging financial assets for manufactured goods (about which, more below) at the expense of investment and jobs in the US itself.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Macrobond, Invesco. Monthly data to October 2024, as at 15 December 2024.

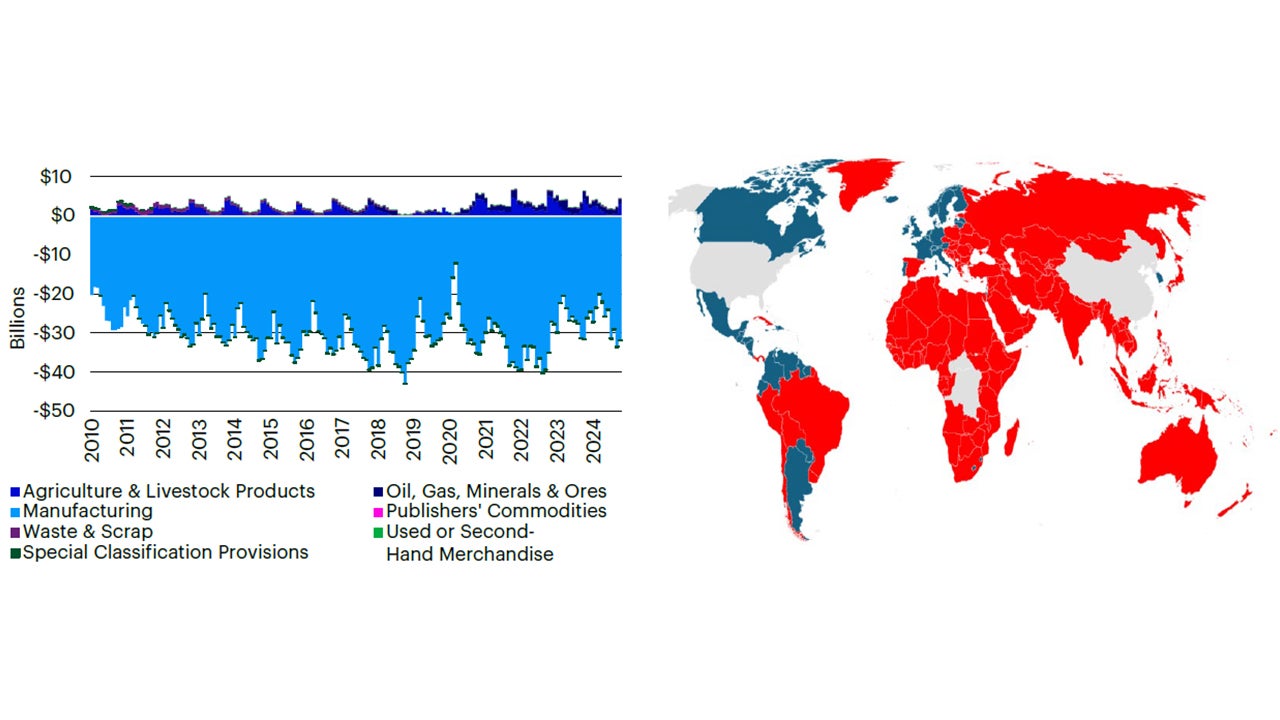

The US China Conundrum: Since China’s 2001 accession to the WTO, US-China bilateral trade has become lopsided. The US exports mainly primary commodities to China, in exchange for manufactures, with a massive deficit. China has replaced the US as the dominant trading partner of most countries outside Europe and North and Central America, even as the US remains the most important security partner in the Mid-East and much of Asia.

Note: Right – red, countries whose total trade with China exceeds that with the US in 2023; others, blue. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, China National Bureau of Statistics, Macrobond, Invesco. Left, monthly data, billions of current USD. All latest available, as at 19 December 2024.

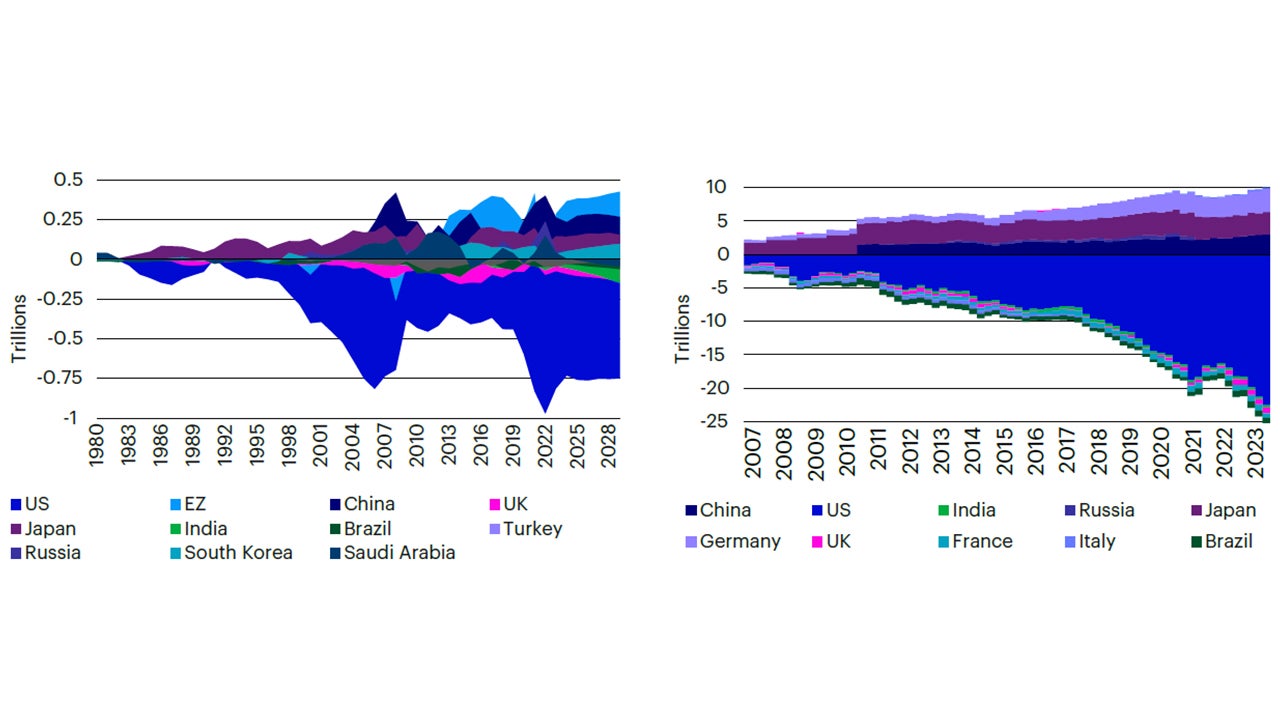

Continuous US external deficits and the collapsing NIIP: US trade and current account deficits persisted for decades, yet the US Net International Investment Position – the stock of US assets held by non-residents – was slightly negative but remarkably stable until the GFC. How could large, growing and persistent deficits fail to translate into rising obligations to the rest of the world? The standard explanation for this conundrum was that US claims on trade/investment partners tended to perform better than its partners’ claims on the US. This was largely because the latter were mainly fixed-income claims (Treasuries, Mortgage-Backed Securities, and Investment Grade). In contrast, US claims on other countries were more equity-like direct investments by corporates with higher income, dividends etc., that boosted the value of US foreign assets.

While we tend to agree with this standard explanation of past performance, our view of what has changed to account for the recent collapse in the US NIIP speaks to Team Trump’s frustration with trading partners. Since the GFC and the Eurozone Crisis, the US appears to have become a bit of a victim of its own success. Its outperformance in growth, in per capita GDP and productivity gains have all translated into dramatic equity outperformance, not least because of the role of US tech giants in the Fourth Industrial Revolution while US external financing has shifted from fixed-income, including dollar reserve purchases by central banks, to private-sector buying of US stocks.

Team Trump, however, worries that this success will turn into failure on a massive, national scale: On current trends, US industry in general, including the defence-industrial base, will continue to be hollowed out. Domestic assets and their income will keep being sold to surplus countries because of a lack of market access for US exporters, not just because of superior US economic and financial performance. Inequality will continue to rise, as will existential risks to national security. China in particular is already the world’s largest economy on a PPP basis. As an industrial producer, China outranks the 10 next largest industrial producers combined. If rivalry were ever to come to conflict, it is already unclear if the US and allies could win, but the further this goes, the greater the risk of defeat.

Note: Current US Dollars.

Source: IMF, Macrobond, Invesco. Annual data to 2023 and IMF WEO forecasts to 2028; all as at 25 October 2024.

Retaliation versus negotiation: We believe the various facets of US relationships will prevent a generalized trade conflict, though some retaliation against US tariffs seems very likely, especially by China. We see no substitute for the US as an export market. The other major, persistent deficit economies – UK, India, Brazil and Turkey, etc. – are not large enough to absorb global export surpluses, if the US were to become truly isolationist. What’s more, China aside, most major surplus countries are US treaty allies or friends, so seem likely to negotiate, as Japan did in the 1980s.

Over time, we would expect “like-minded” countries, in a phrase from the Biden era, ideologically similar democracies, to eventually cooperate with the US on trade, as on defense spending. We don’t expect renewed trade liberalization, but rather increased purchases of US exports, including military equipment and commodities.

That said, Trump may widen his trade war using high, across-the-board tariffs on China. High direct tariffs along with plans to stop China’s indirect exports to the US via third countries in which its firms set up plants (e.g., Mexico, Vietnam) may push Chinese exports into other countries. Their sheer size and low cost (which the US and EU allege is subsidized) could impose severe competitive, even existential pressure in industries they need to sustain for political or national security reasons (i.e., for substantial onshore industrial capacity in case of trade disruption).

Other countries may already be following the US in imposing trade restrictions on China. A key side effect of Biden’s 100% China EV tariff might be to divert exports to the EU, overwhelming its auto sector. The EU complained about protectionist US industrial policy but imposed its own EV tariffs on China, albeit significantly lower than the US tariffs. Brazil also put tariffs on steel from China, following the US. India has also raised tariffs and other trade/investment restrictions on China, reflecting border tensions that persist despite recent improvements in relations.

Geopolitical trading blocs may thus be forming already. The US may focus on North America, Europe, Japan, South Korea, India, etc., China more on the Mid-East, Latin America, Africa. Still, we do not expect economic fragmentation on China-US lines because other governments will likely try to avoid picking sides. On one hand, access to US export markets and financial markets, and security partnerships remains crucial for many countries. On the other hand, China’s importance as a trading partner for many countries, including those closer to the US, is likely to keep many doors open. As a result, China and the US may have little choice but to compete for influence across the world. Yet such issues suggest that trade and investment is become more geopolitical than macro or cyclically driven. And that in our view calls for active country and sector selection instead of a buy- or sell-the-market investment style.