Global debt mid-year outlook

Overview

Expansionary fiscal policy has driven higher than expected US growth, but going forward, we expect growth acceleration to favor the rest of the world versus the US.

Given rich long-term valuations and high funding needs, the US dollar looks vulnerable, and investors in global debt may benefit as the Fed moves to reduce rates.

Improving global growth and loosening financial conditions should benefit global fixed income, and we see the normalization of yield curves as the largest structural anomaly that could generate excess returns as it corrects.

As US growth continues to surprise to the upside, 2024 is shaping up to mirror the last few years, in which US growth exceptionalism seemed to be the rule. Yet this year, the US is not alone in its post-pandemic resilience, and global growth is also surprising positively. Until recently, the US’s domination of the global landscape has hindered the ability of other developed and emerging market central banks to run independent monetary policy. But we believe this dynamic will shift — once the US Federal Reserve (Fed) begins its cutting cycle later this year. In the meantime, we believe we are already in a risk-friendly environment, one that is especially favorable for assets that benefit from global growth.

Global macroeconomic outlook

We are seeing improving global growth conditions, led by emerging market countries, such as India, and supported by resilient US growth. We expect global growth to broaden over time, as Europe recovers from a very weak year, dragged down by Germany. Germany’s industrial sector has faced well-known pressures, such as elevated energy prices and China’s concerted export push into electric vehicles, but the rest of Europe looks robust, thanks to resilient consumers and a deepening manufacturing cycle.

China’s growth outlook remains uncertain. Government measures appear sufficient to support growth at market consensus levels of 4% to 5% for 2024. But Asia remains the weak link in global growth, except for India, which has provided exceptional nominal and real growth, and we expect that to continue for the foreseeable future.

We do not believe there is a high probability of a global or US recession in the next six to 12 months. Any differentiation or acceleration in growth will likely favor the rest of the world compared to the US, as the global manufacturing cycle picks up while the US continues its above trend growth, but at a steady pace.

Higher than expected US growth has been driven primarily by expansionary fiscal policy. While focus remains on monetary policy, it has been the remarkably effective use of fiscal policy that has been the primary driver of US growth and inflation. Through a mix of grants, subsidies, and tax incentives, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act have effected significant changes in US industrial policy that the rest of the world has been unable to match to date.

Going forward, global economic conditions will likely also depend on the global capital expenditure cycle, which is facing competing demands for capital from not only the green transition that is under way, but importantly from the global “arms race” in artificial intelligence (AI). The CHIPS Act gave the US a significant head start and, given its extensive technology ecosystem, the US has been able to distribute USD54.7 billion of the allocated funds, which have fostered another USD348 billion of announced projects.1

Distributing earmarked funds has been more difficult for other countries which do not have large technology infrastructure footprints, such as Spain. Given the high capital intensity of AI, we would expect to see the capex cycle broaden as countries build out their technology footprints. In terms of existing projects, significant plans have been announced, but the spending associated with them is just getting underway, so we expect their implementation to help sustain the current growth cycle.

While it remains early in the capital expenditure cycle, we are starting to see the implications in the US, with an uptick in productivity clearly visible in macro data and corporate earnings. Nominal growth in the US has averaged nearly 6% over the past year alongside falling inflation, and this is likely due to improving productivity. Productivity increases are typically cyclical and targeted fiscal spending can provide a boost for periods of time.

As a result, the ability of the US to escape secular stagnation through the effective use of fiscal policy has dominated the global picture, and we expect resilient economic growth to continue. Nevertheless, this escape has come at a high cost, with US budget deficits close to 6% of GDP in a full employment economy. While we do not expect the US to have difficulty funding itself, this fiscal profligacy will likely have implications for monetary policy and markets.

Monetary policy

We expect generally easier monetary policy to continue to unfold globally. As disinflation proceeds, albeit slowly, most central banks will likely continue to ease monetary policy, with the exception of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) and possibly certain Asian central banks, such as the Bank of Indonesia. Broader central bank easing, however, will probably be limited by US Fed policy, which is influenced by US growth and the Fed’s reaction to US inflation. While policy divergence is likely to continue, with major central banks, such as the European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Canada, and Bank of England, expected to ease further in the second half of this year, the Fed remains the limiting factor in terms of the magnitude of other central banks’ actions.

The case for global easing is based on falling inflation, which is likely to persist as productivity improves. This should allow the Fed to ease this year. At the most, we expect a shallow easing cycle or mid-cycle adjustment to keep the growth cycle strong. Such an easing cycle in the US is unlikely to extend beyond four to six cuts for the entire cycle. This should allow the major developed market central banks to ease more, but within limits. While the ECB’s cycle may be deeper than the Fed’s, it is unlikely to reach the neutral rate, estimated at around 1% to 2%. Similarly, the Fed will likely limit the easing cycle in emerging market countries, with Brazil explicitly linking its shorter cutting cycle to the Fed’s delayed start. There are constraints to policy divergence, with the primary transmission mechanism being currency markets, as we have seen with the BOJ’s recent intervention.

Rates market outlook

In rates markets, we expect income to be the primary driver of returns, with the normaliza-tion of yield curves being the largest structural anomaly that can generate excess returns as it corrects.

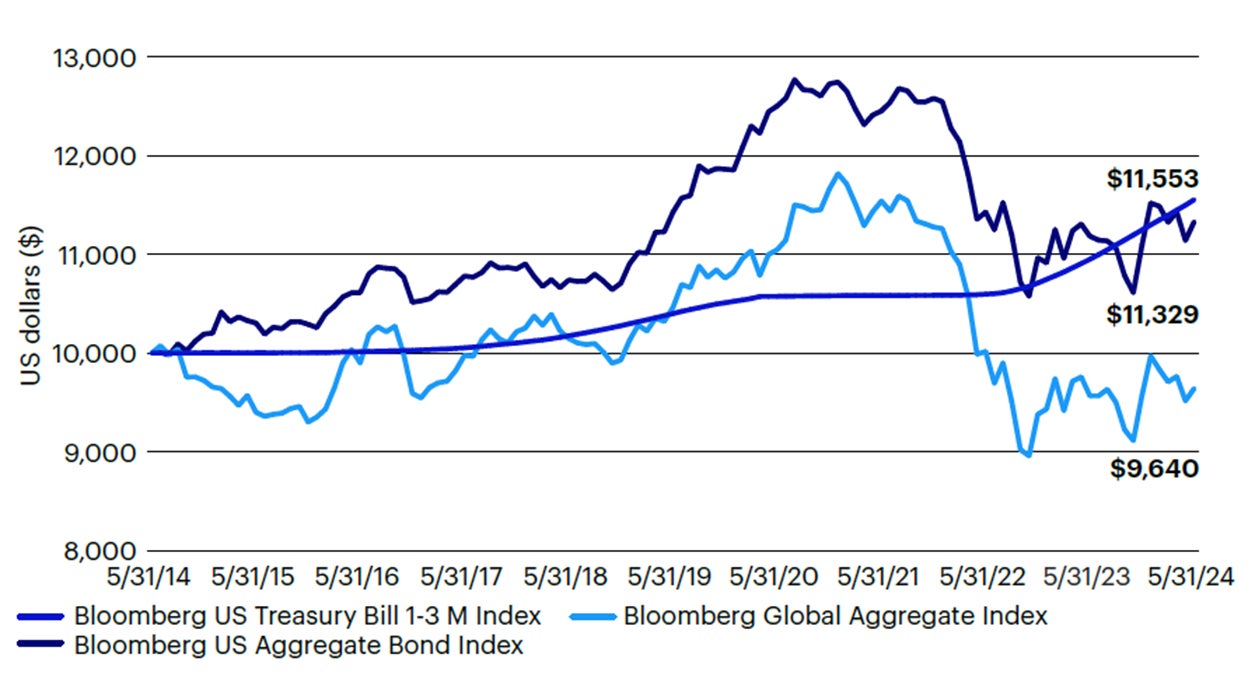

Investing in global rates continues to be a challenge, as global yield curves have remained inverted for an extended period – leaving investors with a decade of risk with no return. Over the past decade, US three-month Treasury Bills have outperformed the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index by a small margin, and because of US dollar strength, the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index by a much wider margin. It should be pointed out that the aggregate indices include corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities, which are lower credit quality than Treasury Bills, so when adjusted for credit quality, the return outcome is worse.

Source: Morningstar, as of May 31, 2024. Assumes $10,000 initial investment, for illustrative purposes only.

An investment cannot be made in an index. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Given the current shape of the yield curve, investors will likely sustain longer periods of underperformance versus Treasury Bills, unless short-term rates decline and curves steepen globally. If long-term rates decline and curves do not dis-invert, however, then any excess return over Treasury Bills will likely be lost to negative carry over time. To achieve sustained excess returns, Treasury Bill rates would have to be lower than longer-term rates and remain so for a sustained period to compensate for the higher volatility of returns of the US Aggregate Index.

While Figure 1 is a snapshot of one time period, inversion has reduced the Sharpe ratio for bond market excess returns over Treasury Bills for even longer time periods. This is true not only for the US market, but for almost all developed markets. To restore some rational relationship between risk (volatility) and return, we believe that most developed market yield curves will ultimately have to steepen. This may happen through a decline in short-term rates, a rise in long-term rates, or both, depending on market structure. In the US, given the very high funding requirements, we expect long-term rates to rise and short-term rates to fall over time. With similar circumstances across most markets, we therefore continue to believe that long-term rates offer limited value. As a result, developed market government bonds generally offer higher income but little compensation for risk relative to the risk-free rate, in our view.

We find emerging market rates to be in a similar bind. In emerging markets, yield curve inversion is possibly more extreme, and therefore short-term rates need to fall sustainably below long-term rates to restore balance between risk and return. In Asia, where interest rates never rose sharply, there are limited opportunities, except in India and possibly Indonesia, where high growth and higher demand for capital should result in high returns for investors for the right reasons (i.e., a higher return on capital and higher income for bond market investors). A significant opportunity in rates remains in Latin America, where for structural reasons, inflation spiked higher and central banks’ orthodox responses have led to high rates both in nominal and real terms, and therefore value in markets. Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia should all offer opportunities for rate compression to developed markets, along with curve steepening.

Currency market outlook

Currency market drivers are centered on the US: monetary policy with rates remaining higher for longer, economic resilience, strong equity market performance, and very high fiscal spending and therefore funding requirements, have created competing forces buffeting the US dollar. US economic performance underpins the strength of the dollar, while the very high funding needs of the government provide reason for weakness.

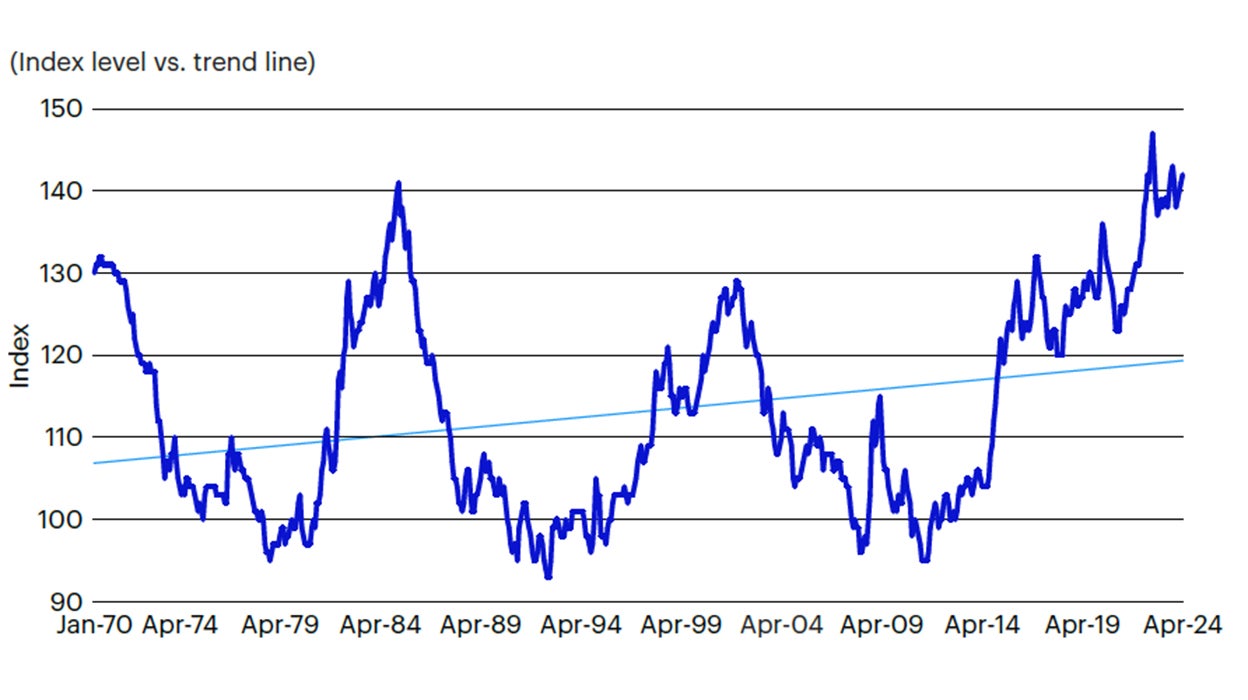

The US dollar is still close to its 50-year high in real terms.2 This valuation, combined with very high funding requirements, should place long-term structural pressure on the US dollar going forward. Two conditions that we believe will need to be met for the short-term cyclical outlook to turn negative is a reduction in the torrid pace of US equity returns and the initiation of the Fed’s easing cycle. The magnitude of the easing cycle will likely be important for currencies but may be less important than for rates markets.

In a market environment of resilient global economic growth, we prefer high carry currencies. It has been possible to extract currency carry in a relatively efficient manner over the past year, and we believe this will continue as long as global economic activity remains robust. In such an environment, we prefer higher yielding currencies, such as the Mexican peso, Brazilian real, Polish zloty, Indian rupee, and Colombian peso. We prefer to fund this long exposure through underweights in the US dollar (as the base currency) but also through the euro, yen, and Chinese yuan. Key risks include geopolitics and elections, and the potential for global protectionist trade policies.

Source: Bank of America. Data as of May 31, 2024.

Credit market outlook

The current environment is credit friendly, in our view, and credit has performed well. But positive performance leaves it susceptible to economic shocks, as spread levels are exceptionally tight. While yield levels are attractive from a historical perspective, it is primarily the underlying US Treasury level that is attractive. As a result, we expect excess returns to be much lower going forward simply due to current rich valuations. From a relative standpoint, we believe that currency carry can offer better value at this stage. In this environment, we continue to be underweight credit overall, selectively focused on US mortgage-backed securities, European bank AT1s, and emerging market high yield credit.

Conclusion

Overall, the outlook is favorable for assets that benefit from global growth, in our view. Given that the Fed has effectively negated the prospect of increasing rates, and the significant probability remains that it will lower rates this year, there is growing room for other central banks to ease policy. As a result, we believe we are in a risk-friendly environment. While significant capital gains from falling rates may be unlikely, earning income remains very attractive. Additionally, as the US dollar is vulnerable, due to rich long-term valuations and high funding needs, investors in global debt may benefit as the Fed moves to reduce rates.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

The values of junk bonds fluctuate more than those of high quality bonds and can decline significantly over short time periods.

The risks of investing in securities of foreign issuers, including emerging market issuers, can include fluctuations in foreign currencies, political and economic instability, and foreign taxation issues.

The performance of an investment concentrated in issuers of a certain region or country is expected to be closely tied to conditions within that region and to be more volatile than more geographically diversified investments.

Footnotes

-

1

Source: Semiconductor Industry Association. Data as of June 12, 2024.

-

2

Source: Bank of America. Data as of May 31, 2024.