Evolution of the green bond market

The increasing importance of Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) considerations to investors has meant asset managers have had to adapt their investment processes. Investor ESG requirements range from low level exclusion to positive impact investing (where financial outcomes take secondary importance) and all points between.

The new European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde has also stated her desire to place climate change at the heart of the ECB’s upcoming monetary policy review suggesting that the focus on ESG is likely to become ever more important. In December 2019, the European Union (EU) reached an historic agreement on the EU Green Taxonomy – a common classification system to determine whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable.

A key factor in the ESG investment approach is the development of the green bond market. The purpose of this article is to examine the structure and composition of this corner of our asset class, including:

- Size, depth and composition of the market

- Recent developments of more innovative structures

- Demand and the impact on pricing

- Potential for further structural influences

Size and depth of the market

According to Bloomberg there are in excess of 1,600 green bonds in issue (20 November 2019), including bonds from governments and investment grade, high yield and non-rated corporates. Coupons range from -0.7% (a floating rate CHF bond from a Swiss insurer) to 15.5% (a Chinese non-rated house builder issuing in USD).

The ICE BoAML Green Bond Index (‘The Index’) has data back to December 2010. It tracks the performance of securities issued for qualified ‘green’ purposes. Qualifying bonds must have a clearly designated use of proceeds that is solely applied toward projects or activities that promote climate change mitigation or adaptation or other environmental sustainability purposes. The index includes investment grade rated debt of sovereign, quasi-government and corporate issuers.

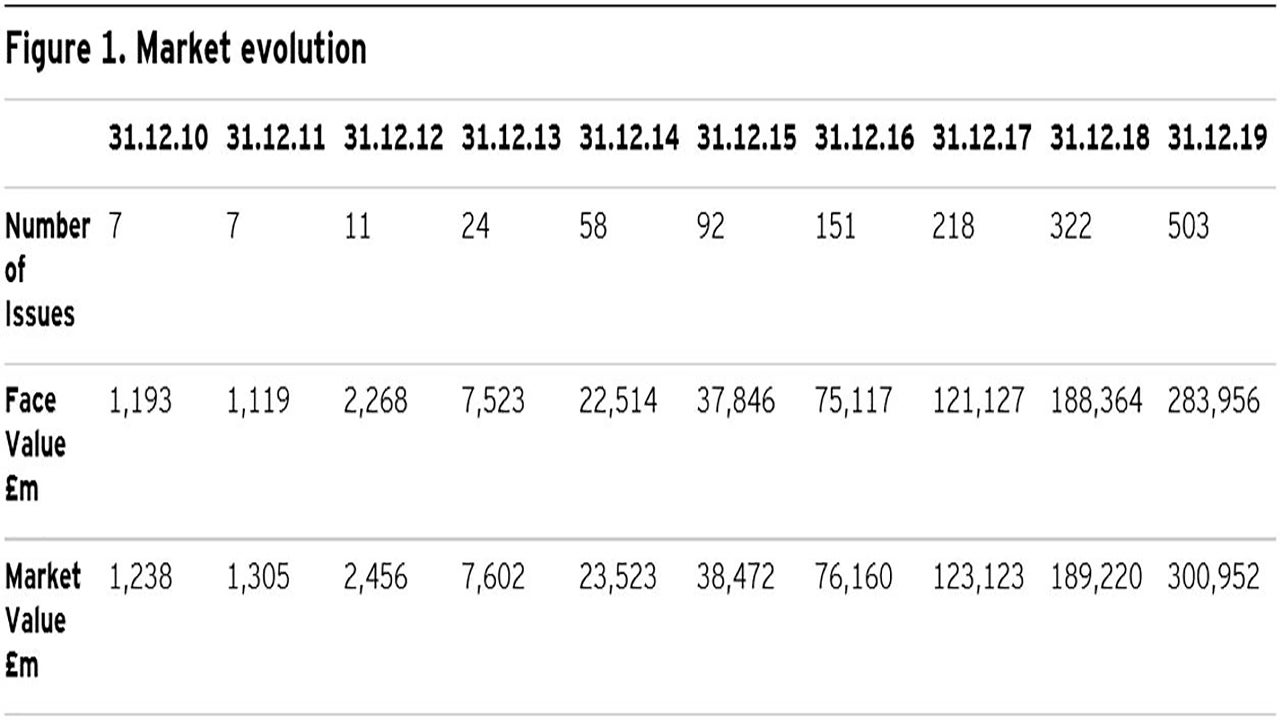

The index launched in October 2014 but with retrospective data back as far as 31 December 2010 at which time the index included just 7 bonds issued by Asian Development Bank, European Investment Bank and International Bank for Reconstruction & Development with a face value of £1.2bn. Quasi governments still form a substantial portion of the index. The growth of this index is shown in figure 1.

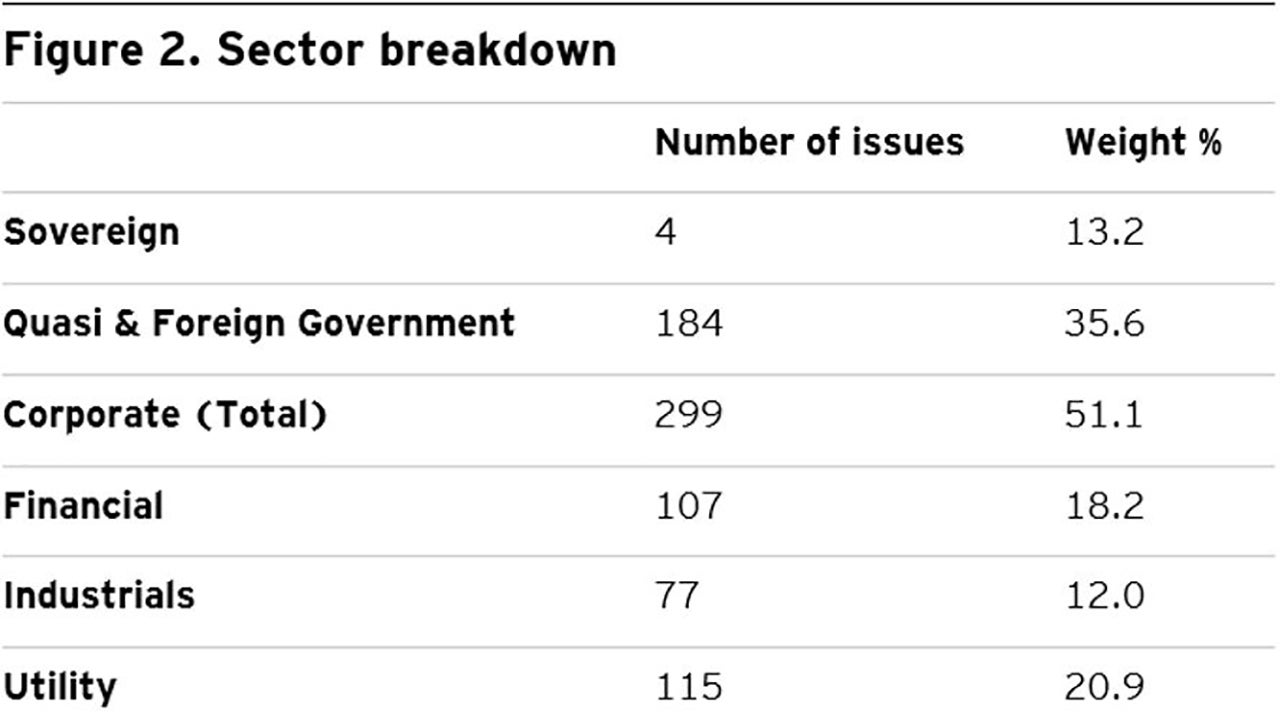

The Index is dominated by EUR denominated bonds which account for 62.6% of the total. This percentage is split evenly with 31.8% (167 bonds) issued by corporates and 30.8% (69 bonds) issued by quasi governments.

USD accounts for 25.9% (of which a third is US corporates, the rest being non-US companies issuing in USD and quasi governments) and third place is CAD at just 3.1%. There are just 11 GBP denominated bonds accounting for 2.3% of the total (5 corporates and 6 quasi governments).

The sector breakdown is 51% corporate, 13% sovereign and 36% quasi governments.

Green bond issuers

It’s when you look at the actual issuers that the green bond market looks interesting.

The quasi sovereigns are obvious issuers of green bonds, issuing to fund development projects. A handful of countries - Belgium, France, Ireland and Netherlands - have also issued to fund environmental projects. A few additional countries – Fiji, Indonesia, Nigeria and Poland – have also issued green bonds although they do not qualify for the index.

Corporate issuance has been a key driver of the growth of the green bond market dominating new issuance and moving the overall index from 40% at the end of 2015 to over 50% currently.

In terms of corporate issuers, issuance is dominated by utilities. This is no surprise as the green bonds tend to be issued to fund renewable projects. A more surprising issuer in this sector is a Chinese state-owned power company, operators of a controversial hydroelectric project in China. The proceeds from this bond were earmarked to finance two renewable energy projects in Europe. The renewable projects are uncontroversial wind farms that are expected to save 2 million tonnes of CO2 over their lifetimes. Proceeds from the bonds are not being used to build new projects but are instead being used to refinance operational projects. While building up a portfolio of European renewable assets in this way is not necessarily a bad thing, it does mean that the direct environmental impact of the bond is quite minimal. This is particularly true since the Three Gorges Dam project remains controversial.

Other more surprising issuers include airports, chemical companies, technology companies and numerous banks. Recent examples include a Dutch multinational bank and a Spanish one issuing senior bonds to “allocate funds to a loan portfolio of new and/or ongoing renewable energy projects” and “eligible green projects” respectively. Banks also have a further part to play in their willingness to finance fossil fuel projects. In September 2019, 33 banks with US$13 trillion of assets announced a Collective Commitment to Climate Action in which they commit to align their business with international climate goals.

More recently we have seen the emergence of SDG bonds – ones associated with a specific UN Sustainable Development Goal. An Italian utility and a regular issuer issued green bonds in September 2019 where the rate of interest is linked to the percentage of the company’s generation capacity accounted for by renewables and another to their greenhouse gas emissions target. In both cases the coupons increase by 25bps if these commitments are missed.

One area that is receiving a lot of attention and is a contentious topic, is the idea of “transition bonds”. Should we acknowledge carbon intensive companies or projects that are transitioning away from fossil fuels even though the actual activity is not green or sustainable? Transition bonds could finance projects aimed at helping the issuer switch to a cleaner way of doing business, particularly if they help with climate goals. A wider range of issuers may be able to issue transition bonds and provide investors with an even greater investable universe. However, others might consider such bonds a case of ‘greenwashing’ – an attempt to make the company appear more environmentally friendly than it really is.

An Italian bank became the first bank to issue a Sustainability Bond dedicated to the circular economy (an economic system aimed at eliminating waste and the continual use of resources) in November 2019. The €750m senior bond attracted demand of over €3.5bn and priced inside similar existing Intesa bonds. Its head of treasury stated “Investors were willing to give up some yield to be involved in this trade”, a clear sign that investors might be willing to put a value on the notion of ESG investing.

Is investor demand driving yields lower?

Although green bonds still only make up a small percentage of the overall market, global interest and demand has soared as banks, sovereigns and companies look to tap into increasing investor appetite.

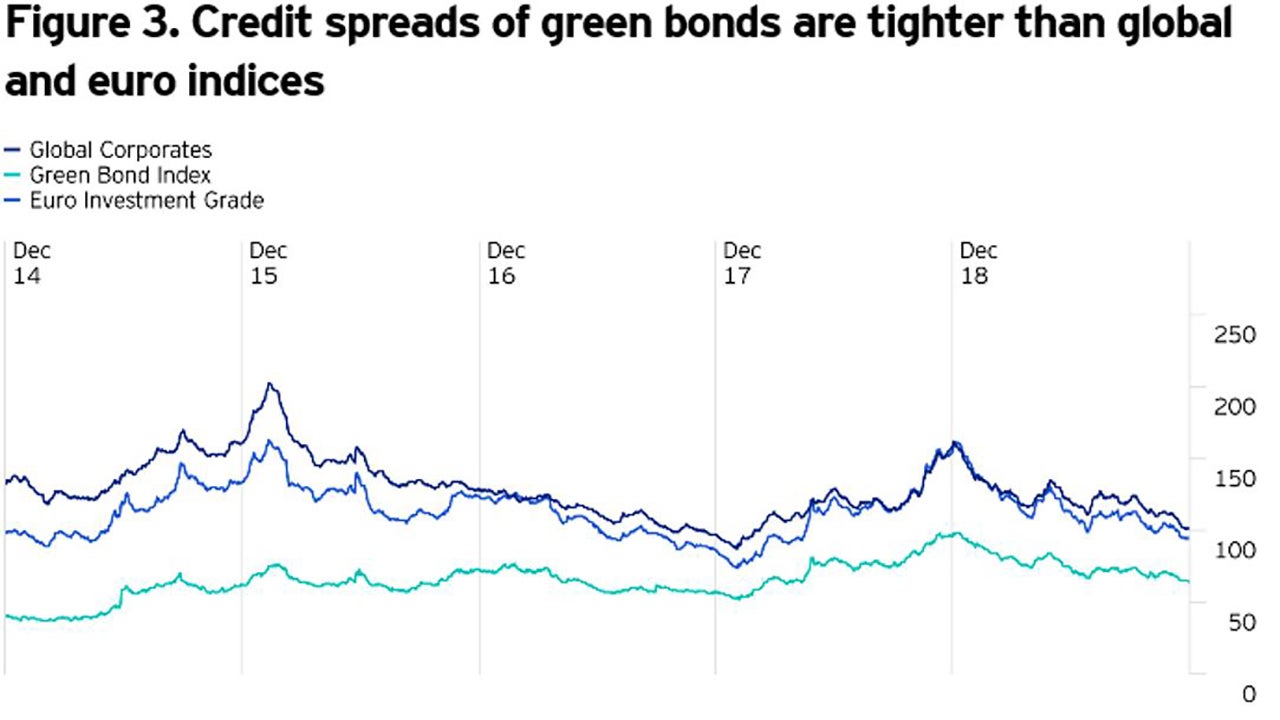

This in turn presents a challenge for investors. As well as the Intesa example above, strong demand for green bonds has, in the opinion of our analysts, seen instances of new issues, which would normally offer a new issue premium, price tighter than the conventional bond from the same issuer.

The above-mentioned Italian utility company’s $1.5bn SDG bond issued in September 2019 saw orders of over $4bn. Creditsights reported that this allowed Enel “to tighten spreads substantially compared to its secondary market curve. Final pricing came in at T+125bp, which we judged to be about 10-15bps inside the secondary market curve”.

We have also started to see green hybrid bonds. A Danish power company recently issued such as bond. Although it is not without risk should the Danish government reduce its 50% stake, it is an issuer we like and hold across some of our funds where appropriate with the investment objective. Demand was strong with EUR3.7bn for the EUR600m issue. Final pricing saw the bond issued with a 1.75% coupon (it was issued at 99 for a yield of 1.85%) from initial talk of 2.375%.

While the Index is not representative of the wider market, you can see in the chart below that the Green Bond Index does trade with tighter spreads that the wider Global and Euro Corporate indices.

Germany has recently announced it will issue EUR 10bn of green bonds in 2020. “Green bonds will be “twin bonds”, issued alongside conventional federal bonds (Bunds) with the same maturity and coupon” (Federal Ministry of Finance, 2019). This will allow a direct comparison and demand for these will allow Invesco’s credit analysts and fund managers to understand what ‘price’ investors are willing to pay to support green initiatives.

Additional structural drivers of demand?

Demand for green bonds could be further boosted by central banks and climate change initiatives. As mentioned in the Introduction, the ECB wish to consider climate change as part of their monetary policy review. Might this see a preference for green bonds in its QE bond purchase programme leading to further spread compression? Or simply encourage additional green bond issuance? Elsewhere, the European Commission has launched the European Green Deal, a series of policy initiatives aimed at putting Europe on track to reach net-zero global warming emissions by 2050.

Conclusions

Client demand for responsible investment has led to increasing issuance of green bonds and other structures. In turn this places challenges on investors to ensure both that pricing and use of proceeds is appropriate and adhered to.

Where possible, all else being equal, we would prefer to select a green bond over the equivalent non-green bond. However, should investing through an ESG approach lead us to buy green bonds or instead reward those companies that are ‘best in class’ in each sector? This is one of the questions we are currently considering as we look to evolve our ESG approach and will address subsequently.

Alister Brown is Fixed Interest Product Director for Invesco in Henley-on-Thames in the UK.