Demystifying three themes that are critical to China’s future development

Executive Summary

China risk assets have experienced broad selloff since 2021, driven by four major factors: real estate sector crisis, Covid developments and lockdowns, economic growth slowdown, and heightened regulatory and geopolitical risks. A lack of confidence and understanding of China’s future path has resulted in global investors reallocating out of China assets.

As a reference, China offshore USD bonds registered a -17.69% return as of end-November while China stocks registered a -41.38% return.i

Source: Bloomberg, data as of November 30, 2022. Past performance does not guarantee future results. An investment cannot be made in an index.

However, we see light at the end of the tunnel. We believe China is on the right track to tackle its challenges and enter a new phase of more sustainable and higher quality growth. In this paper we will elaborate on three main areas to allow investors to better understand the roadmap China is currently on and our expectations of policymakers’ plans. These include: 1) Property market restructuring; 2) Zero Covid policy; 3) Internal circulation and Common Prosperity.

We believe global investor confidence can be regained as these themes play out and these themes can be better understood by a wider investor base. The pullback in asset prices over the past two years provides a better entry point for long-term investors. We believe China assets are becoming increasingly more attractive and will continue on this trajectory in 2023.

1) Property Market Restructuring

What has driven the rise of China’s commercial housing market?

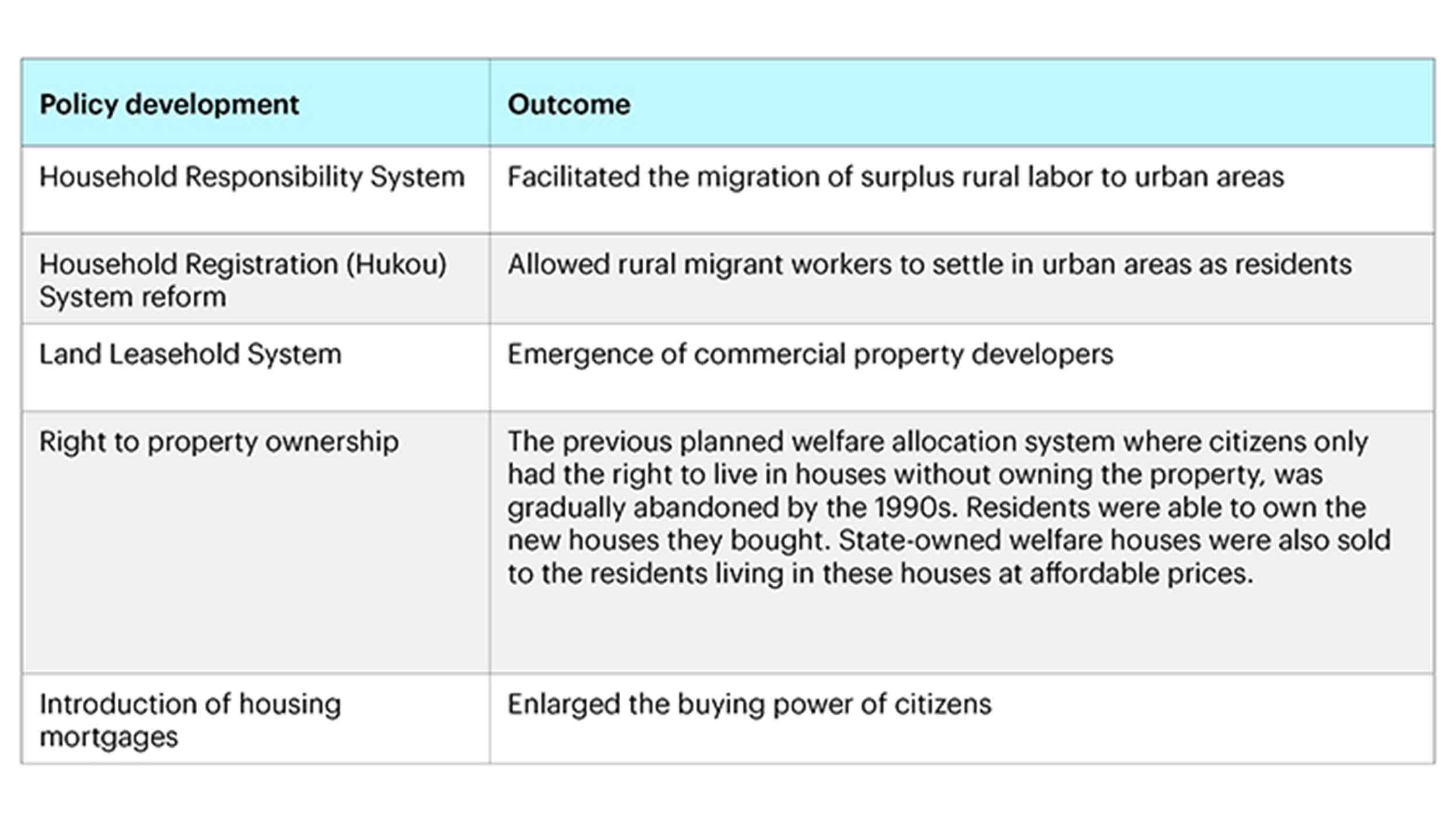

Since China’s “Reform and Opening-up” policy in 1978, the real estate sector has become one of the major pillar industries responsible for the country’s economic boom. Over time, policymakers in China replaced the welfare-based urban housing system with a market-based housing provision scheme. The demand for commercial urban housing was also boosted by a series of policy developments.

Source: Invesco, for illustrative purposes only.

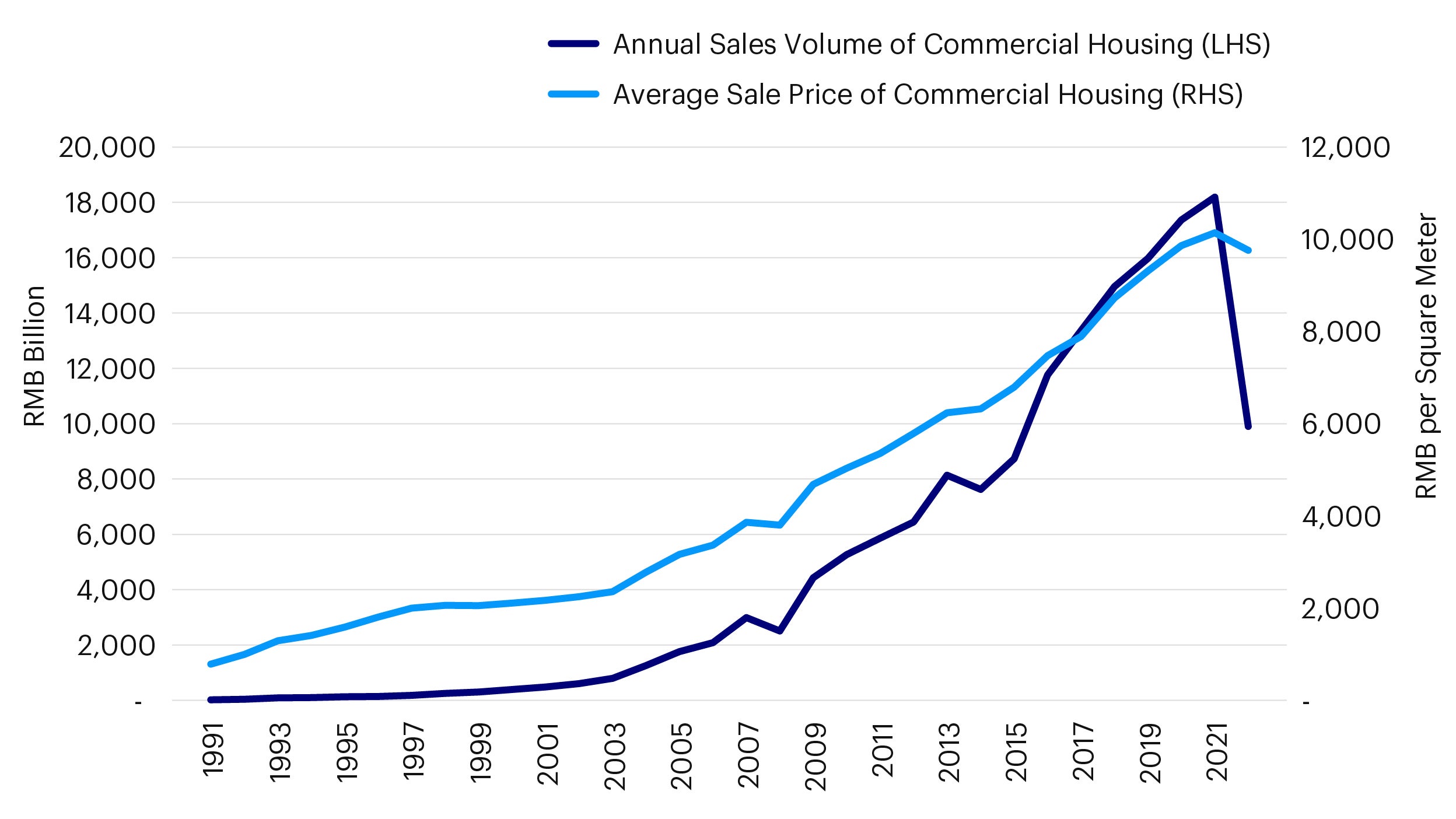

Since these initiatives came into effect, China’s real estate market has experienced rapid and prolonged growth. Over the past 30 years, both the sales volume of commercial housing and average sale prices of commercial houses have skyrocketed.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, Invesco, data as of September 30, 2022.

What are the causes of the current property market restructuring?

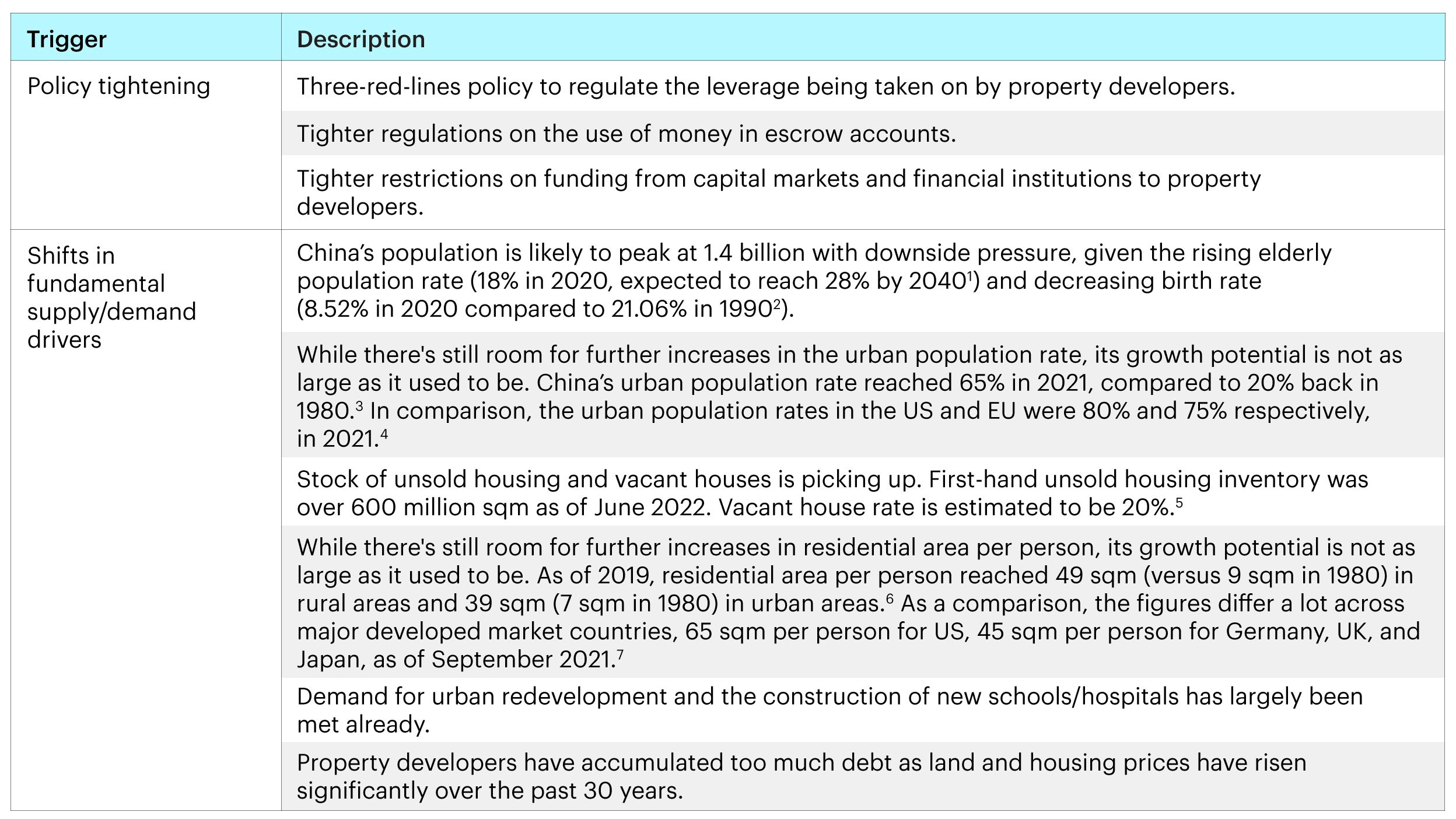

China’s real estate market entered a new phase in 2018, as growth slowed down and regulation intensified. The annual sales area of commercial houses grew from 30 million sqm in 1991 to 1.7 billion sqm in 2017, up by more than 56 times.ii This figure stayed roughly stable until 2021. Since early 2021, major developers in China, especially private developers, started to suffer from liquidity issues and many went into default. This could be partly explained by the tighter sector regulations but was fundamentally due to long-term supply/demand dynamics.

Sources: 1. The elderly population rate refers to the percentage of population of people over 60 years old. 2020 figure is from China’s Seventh National Population Census, data as of November 1, 2020. 2040 forecast is from World Health Organization. 2,3. National Bureau of Statistics of China. 4. The World Bank, data as of September 15, 2022. 5. First-hand unsold housing inventory refers to commercial houses that have been approved for selling but not sold yet. Figure is from CRIC China, data as of June 30, 2022. Source for Vacant house rate is Li Gan, an economics professor at Texas A&M University, data as of October 20, 2021. 6. National Bureau of Statistics of China. 7. China Ping An Research, data as of September 2021.

What is our outlook for China’s property market?

We believe the restructuring process is painful but necessary for China’s property sector to have a more sustainable and healthy growth model. We expect the real estate industry to enter a new era of development in the next five to 10 years with the previous standard development model no longer suitable. We anticipate that:

- Chinese property developers will stay away from the previous development model of “high leverage, high debt, high turnover”. We expect them to stop aggressively bidding for land at extremely high prices in order to build new houses.

- Chinese property developers will focus on development projects based on actual market demand and avoid expansions in non-core businesses.

- The number of property developers will shrink, with higher quality developers taking more market share. State-owned (SOE) property developers will take more market share than privately-owned enterprises (POE), reversing the trend in previous years.

We expect that China’s property sector will have healthier and more sustainable development starting from 2023, given that:

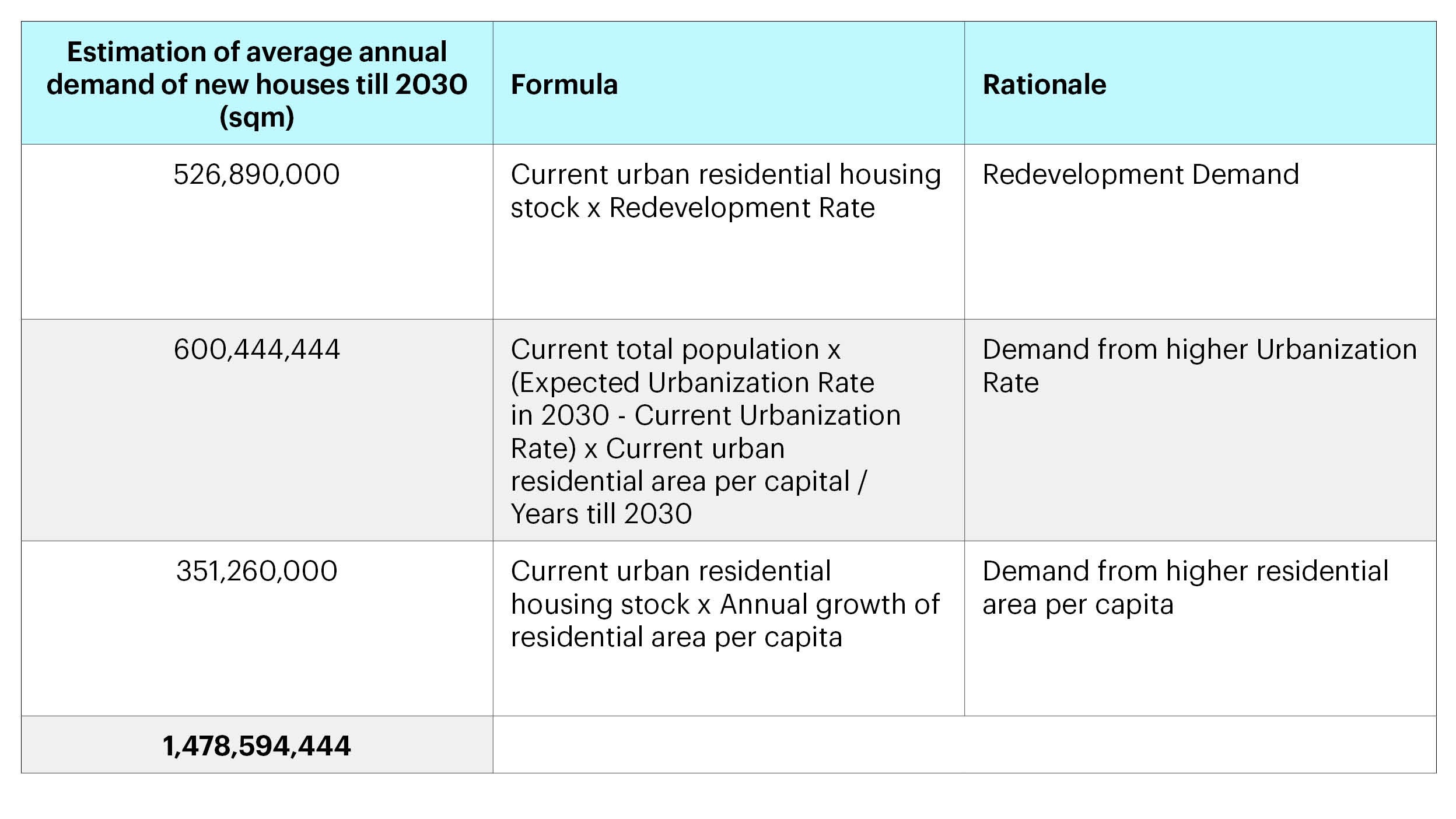

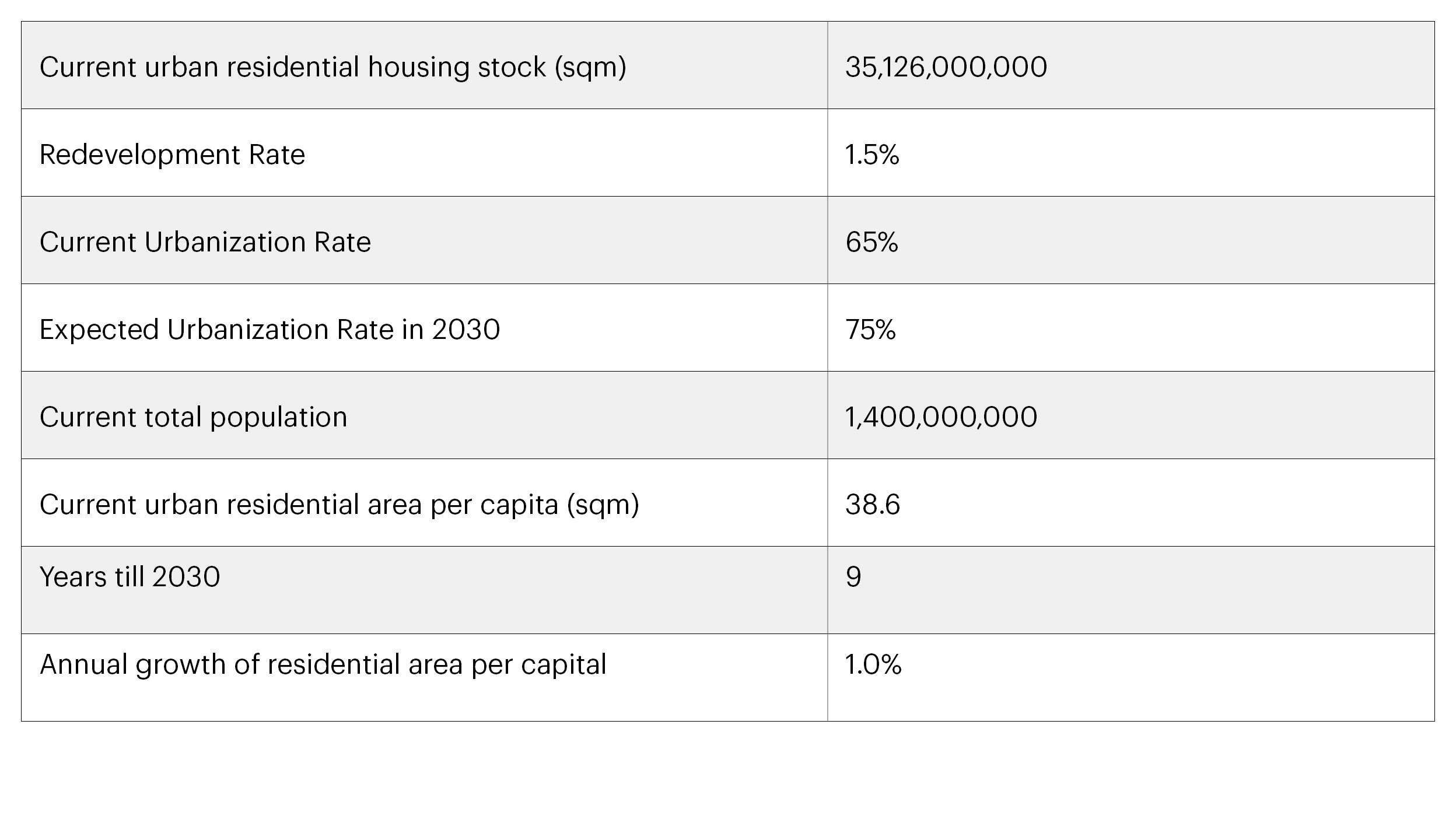

- After the restructuring in China’s property sector over the past two years, yearly commercial housing sales have become much more sustainable in the medium to long term based on fundamental supply and demand factors. In the first nine months of 2022, commercial housing sales reached around 1 billion sqmiii. We estimate that the average annual demand of new houses till 2030 will be around 1.5 billion sqm, assuming a 1.5% redevelopment rate, 1% annualized growth on residential area per person, and growing urbanization rate to 75% by 2030 (detailed calculation shown in Appendix). As such, we expect fundamental supply and demand to be at an equilibrium in 2023.

- The leverage ratios for major property developers have recently dropped to a healthier level. More accommodative easing measures were also announced in mid-November to help address the liquidity issue faced by private developers, including a 16-measure rescue package and “three-arrows” easing measures (loans, debt and equity). The property sector remains important for China. Previous rounds of policy tightening were not intended to eliminate the sector, but to control the market bubble and target a more sustainable long-term growth pattern going forward.

2) Zero Covid policy

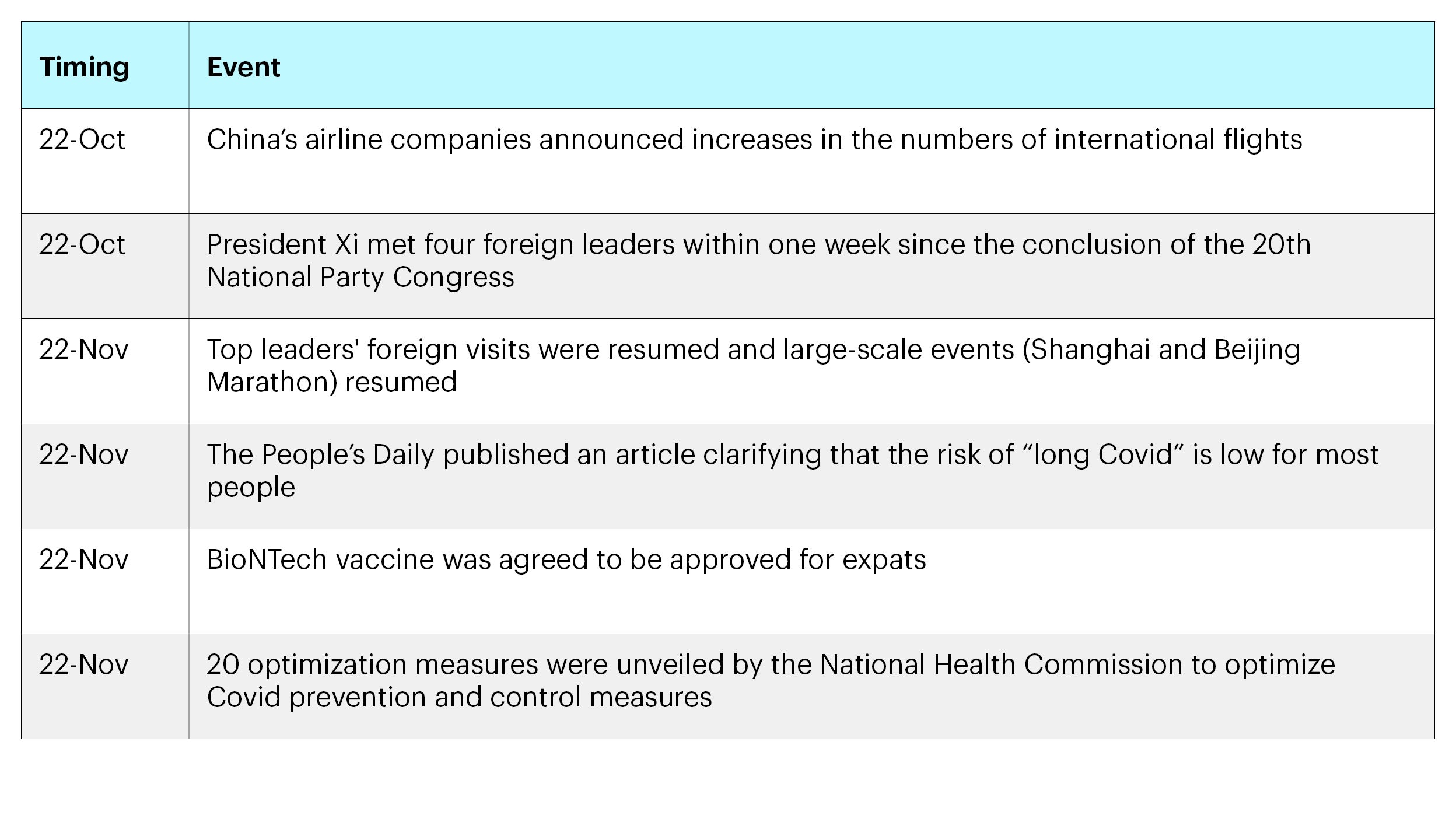

The implementation of dynamic zero Covid policy in China, which involves mass testing, strict quarantine measures, and regional lockdowns, has negatively impacted economic growth and investor confidence in China over the past year. However, since early November 2022, a series of events suggest that China is embarking on a clearer path toward the end of the zero Covid policy.

Source: Invesco, for illustrative purposes only.

We believe that policymakers have learnt from the reopening experiences elsewhere around the world and have taken into consideration China’s unique situation. Chinese officials are making good progress in achieving the four pre-conditions needed for a full reopening and we expect these pre-conditions to set good foundation for a smoother process once reopening occurs.

Pre-condition 1: Boosting vaccination rate, especially that of the elderly population

A critical reason why China has stuck to its zero Covid policy is because of its large elderly population, as emphasized by President Xi in multiple press meetings. As such, it’s natural for Chinese policymakers to focus on boosting the vaccination rate for elderly population to prepare for reopening. Chinese health authorities claimed on November 29 that 66% of elderly people over 80 years old had received booster shots, which was up from 40% as of November 11.iv According to Caixin’s December report, Chinese officials have made plan to improve the booster vaccination rate for elderly people over 80 years old to above 90%, and for elderly people aged between 60 to 79 years old to above 95%, by end of January 2023.v The targeted higher vaccination rate for the elderly would remove the biggest obstacle for policymakers to relax the strict Covid policy rules.

Pre-condition 2: Availability of effective Covid treatments including oral anti-Covid drugs

The availability of effective Covid treatments is another crucial pre-condition for China’s potential shift away from the zero Covid policy. Given the large population and wealth/resource inequality in the country, oral treatment against the Coronavirus stands out as an important option.

After giving conditional approval to a large global pharmaceutical’s Covid treatment drug Paxlovid in February 2022, Chinese officials have continued to push domestic oral antiviral drugs. Regulators granted conditional approval to Azvudine, the first Chinese-made oral antiviral drug to treat Covid-19 in July 2022. The drug only costs RMB 270 per course, compared to the cost of the imported drug Paxlovid of RMB 2,300.vi

Another domestic oral antiviral drug GST-HG171 was also approved for clinical trials for the treatment of mild-to-moderate Covid-19 in adults in September 2022.

Pre-condition 3: Education to reshape the public perception of Covid

Another key milestone to full reopening is to reduce public concerns around the virus. This is important as many Chinese people are still highly concerned about spread of the virus given: 1) the serious consequences of Covid have been highlighted by the Chinese government over the past 2 years; 2) Lack of education on the difference between the virus from the early Wuhan days and later variants (much milder but more contagious).

We have seen the Chinese government making efforts to change the narrative in this regard. For example, in November, People’s Daily stated that long-Covid is temporary and mild. And a few authoritative experts were also highlighted who gave context to the latest fatalities and severity of the situation.

Pre-condition 4: Availability of medical treatment and equipment to manage high caseloads

In November it was reported that China’s top health authorities vowed to strengthen hospital networks in order to more effectively treat Covid patients. The country will build more hospitals that specialize in treating moderate and severe Covid patients and ensure that intensive care units account for 10% of all beds in these hospitals to tend to the most vulnerable. Earlier in the year, there was also a report that the National Health Commission instructed county-level hospitals to boost medical equipment supplies, targeting Covid treatments, particularly for severe cases.

The safeguarding of hospital capacity to manage high caseloads is a clear sign and a significant step in the reopening process, which could result in the quicker identification treatment of Covid cases in the short-term.

3) Internal circulation and Common Prosperity

Both internal circulation and Common Prosperity are important policy initiatives that Chinese officials have been emphasizing. Neither has been welcomed or widely understood by foreign investors. We believe there are some misperceptions which need to be clarified. These are well-thought initiatives that would bring clear benefits to the economy in the long-term and set a good foundation for more sustainable and high-quality growth.

Internal Circulation

China’s dual circulation strategy was first mentioned by President Xi in May 2020. The strategy places a greater focus on the domestic market, or internal circulation, with less reliance on an export-oriented development strategy given the increasingly unstable external relationships China has with major trading partners including the US and EU.

Internal circulation is a defensive approach by Beijing to prepare for the worst-case scenario as the world undergoes significant geopolitical and economic changes. China’s major trading partners have ramped up their defensive policy actions. The US’ tariffs and other trade barriers, US advanced chip ban, and Huawei ban in both US and EU are all examples of trade protectionism or technology supply chain disruptions that are forcing China to adapt.

As such, the concept of dual circulation was introduced, which focuses on:

- Boosting domestic consumption. This can be achieved by increasing the size of the country’s middle-class population (currently 400 millionvii) and by narrowing the wealth gap.

- Push for technological self-reliance. This involves a supply-side evolution, particularly in areas such as advanced chips that have been and could be sanctioned by the US.

- Reallocation of labor, land, and financial resources to more productive areas.

Improvements in these three areas could lead to higher quality growth.

While some foreign investors are concerned that internal circulation can push China to completely close itself off from the outside world, we believe this is simply not true. While the country can lean more on domestic consumption, we do not expect China to turn away from the international market, as internal circulation is just one part of the dual circulation strategy. Instead, China has cooperated more closely with its partner countries under the Belt and Road Initiative. Rather than becoming a manufacturing hub as part of the old global supply chain order led by the US, China has started to build its own supply chain through its Belt and Road network. The construction of Chinese industrial parks in Belt and Road countries is an example where China has not only helped to speed up the industrialization of Belt and Road countries, but also diversified the export risks for Chinese products.

Common Prosperity

Common Prosperity has emerged as one of the most important concepts in China since it was mentioned by President Xi in August 2021. This is often misperceived to be a Robin Hood-style redistribution of wealth or full equality. However, the goal for Common Prosperity is about creating a society that’s prosperous “overall” rather than “uniform egalitarianism”.

There are three underlying goals under the Common Prosperity framework: 1) Reducing regional inequality; 2) Reducing rural-urban inequality; 3) Reducing sector inequality.

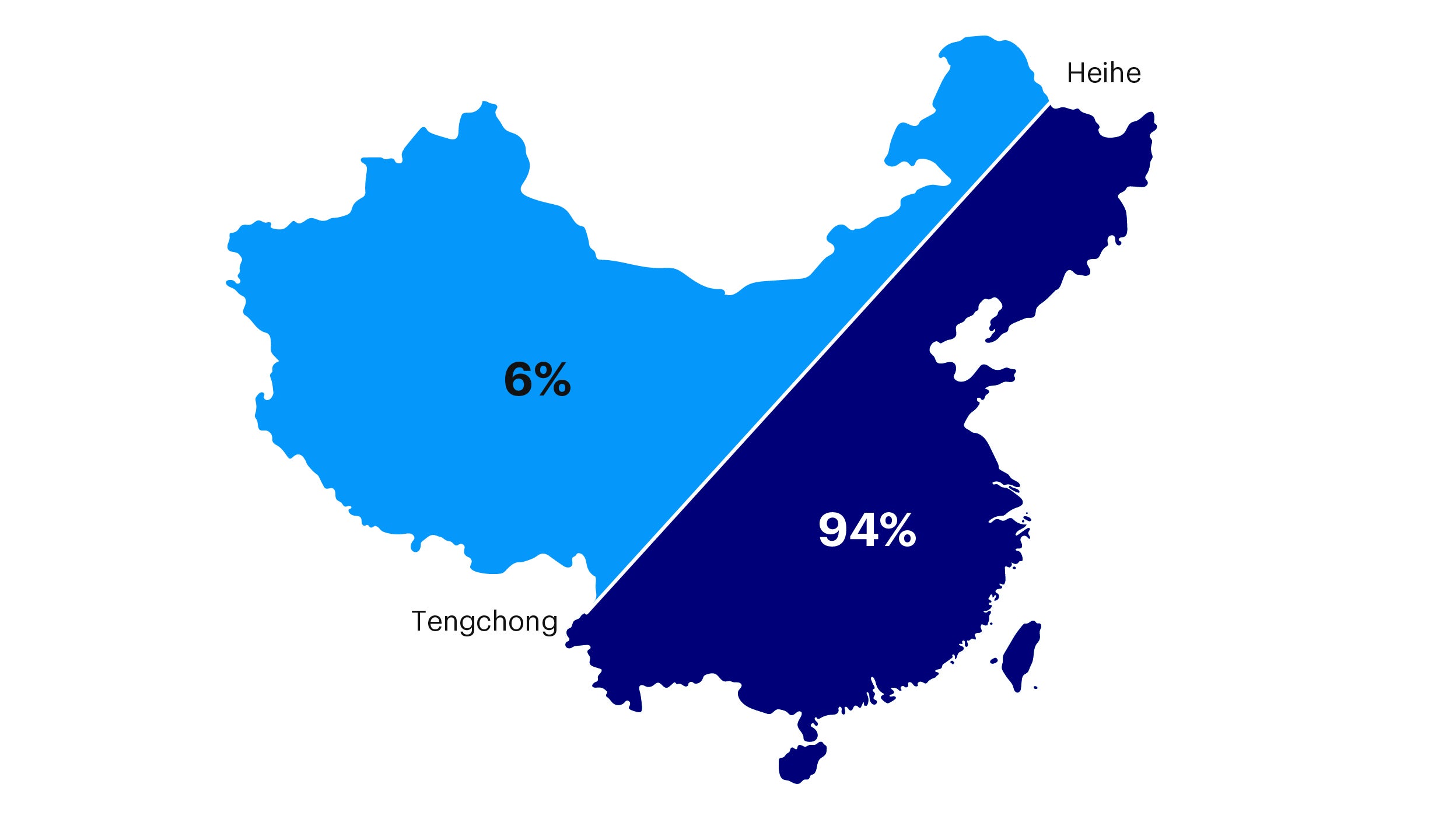

For the regional inequality, the reduction would mainly be achieved by modernized high quality growth in the lesser-developed regions. The Heihe-Tengchong Line was an imaginary border line drawn by demographer Hu Huanyong in 1935. The line illustrated how the China’s population is distributed unevenly. The area to the west of the line comprised two-thirds of China’s territory but contained only 6% of the country’s population. Inversely, 94% of the Chinese lived to the east of the line, on just one-third of the land. The western side of the line was less developed mainly because of natural causes such as weather. As such, we believe this needs to be addressed by modernization and technology.

Source: BigThink, February 2021.

China’s West-East Electricity, Oil and Gas Transfer Projects and the newly built Western China Clean Energy bases are examples of China’s push to develop its western areas. The solar park located in Qinghai is over 600 square kilometers and the electricity that can be produced here can help accumulate wealth for local people of this region. Since China’s “Go West” campaign, the wealth inequality between western and eastern areas has been reducing. Back in 2000, the GDP per capita ratio between the Western and Eastern regions was 1:3.2. This rose to 1:2 in 2020.viii The emphasis on carbon neutrality and achieving peak carbon in China by 2030 can further benefit the Western region as it has been revamped into a high-quality energy base. As illustrated, the reduction of inequality has been achieved not by transferring wealth from the East to West, but by high-quality development in the West itself.

Similarly, in order to reduce rural-urban inequality, Chinese officials have been providing the necessary elements to rural residents to help them accumulate wealth such as through asset investment and use of leverage. The household registration (Hukou) system was also further reformed in recent years to allow rural migrant workers to settle as urban residents.

To address sector inequality, historically, Chinese citizens working in finance, internet, and property sectors have had higher incomes, which was fundamentally driven by looser regulatory policies and more supply of resources to these sectors. Chinese officials have now reallocated the supply of resources more fairly and intervened with tighter regulations on selected sectors to ease the overall burden on citizens.

By implementing these measures, we believe China’s economy and society will be able to benefit in the long-term despite the more recent short-term volatility.

Common Prosperity is also a pre-condition for achieving internal circulation. The push to advance the Common Prosperity framework is expected to increase China’s middle-class population, which can further boost the domestic consumer market. This would set a better foundation for internal circulation and sustainable economic growth. It can also help to promote technological innovation, as the larger the consumer market, the more realistic it can be for technology innovation investments to gain back their original investments and realize profits.

Investment implications

In summary, the volatility in the China market since 2021 has been the result of the real estate crisis, Covid developments and lockdowns, a slowdown in economic growth and heightened regulatory and geopolitical risks. While some of these factors are still playing out and challenges to China’s growth persist, in 2023 we expect that:

- China’s property market will enter a more sustainable growth phase.

- China will gradually pivot away from the zero Covid policy as the four pre-conditions are met.

- Internal circulation and Common Prosperity initiatives will bring about higher-quality, more sustainable, and heathier long-term growth to China.

As the above three themes play out or become better understood by global investors, we anticipate that China assets can enjoy better sentiment and demand in 2023. As such we are positive on China assets in the coming year.

Appendix

Sources: Current urbanization rate and current total population are from National Bureau of Statistics of China, data as of December 2021.

Assumptions:

- Morgan Stanley has forecast that China’s urbanization rate would reach 75% by 2030.ix

- The current urban residential housing stock was estimated by multiplying the total urban population and the urban residential area per capita.

- A 1.5% redevelopment rate is assumed.

- An annual growth of residential area per capita of 1.0% is assumed, so that the current 38.6 sqm would grow to around 42.2 sqm by 2030.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

When investing in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in value.

Investment in certain securities listed in China can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity and/or investment performance.

Footnotes

-

i

Bloomberg, data as of November 30, 2022.

-

ii

National Bureau of Statistics of China

-

iii

National Bureau of Statistics of China, data as of September 30, 2022

-

iv

CNBC, data as of November 29, 2022.

-

v

Caixin, data as of December 1, 2022.

-

vi

China Daily, data as of August 13, 2022.

-

vii

National Bureau of Statistics of China, data as of December 31, 2021.

-

viii

National Bureau of Statistics of China. The GDP per capita ratio for Western region considers of Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Tibet. The GDP per capita ratio for Eastern region considers Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong.

-

ix

Morgan Stanley, data as of November 7, 2019