Understanding ETF trading and liquidity: The Basics

Demand for exchange-traded funds (ETFs) continued to rise from 2022 to 2023 despite headwinds of market volatility. Last year, investors widened the flow gap between mutual funds and ETFs to US$ 1.5 trillion.1

For many years, ETFs have been synonymous with passive “buy and hold” investing. However, with over 10,000 ETFs listed globally, a multitude of investment strategies now exist.2 ETFs now cover a wide variety from passive to active strategies with various shades in between, across a multi-asset spectrum.

Asia Pacific investors have caught on to this. Last year, Asia Pacific domiciled ETFs outgrew European domiciled ETFs for the first time.3 Additionally, Asia Pacific investors use US and EMEA-domiciled ETFs for many reasons such as a broad product range, preferential tax treatment or lower fees.

ETF trading volumes are continuing to break records year after year.4 ETFs are tools for a wide range of investors looking to interact instantaneously in global markets.

As Asia Pacific investors increase their adoption of these vehicles to improve investment outcomes, understanding ETF trading and liquidity is of great importance to not be limited to the top 1% most-liquid ETFs, but to take advantage of the whole ETF universe.

The basics of ETF trading and liquidity

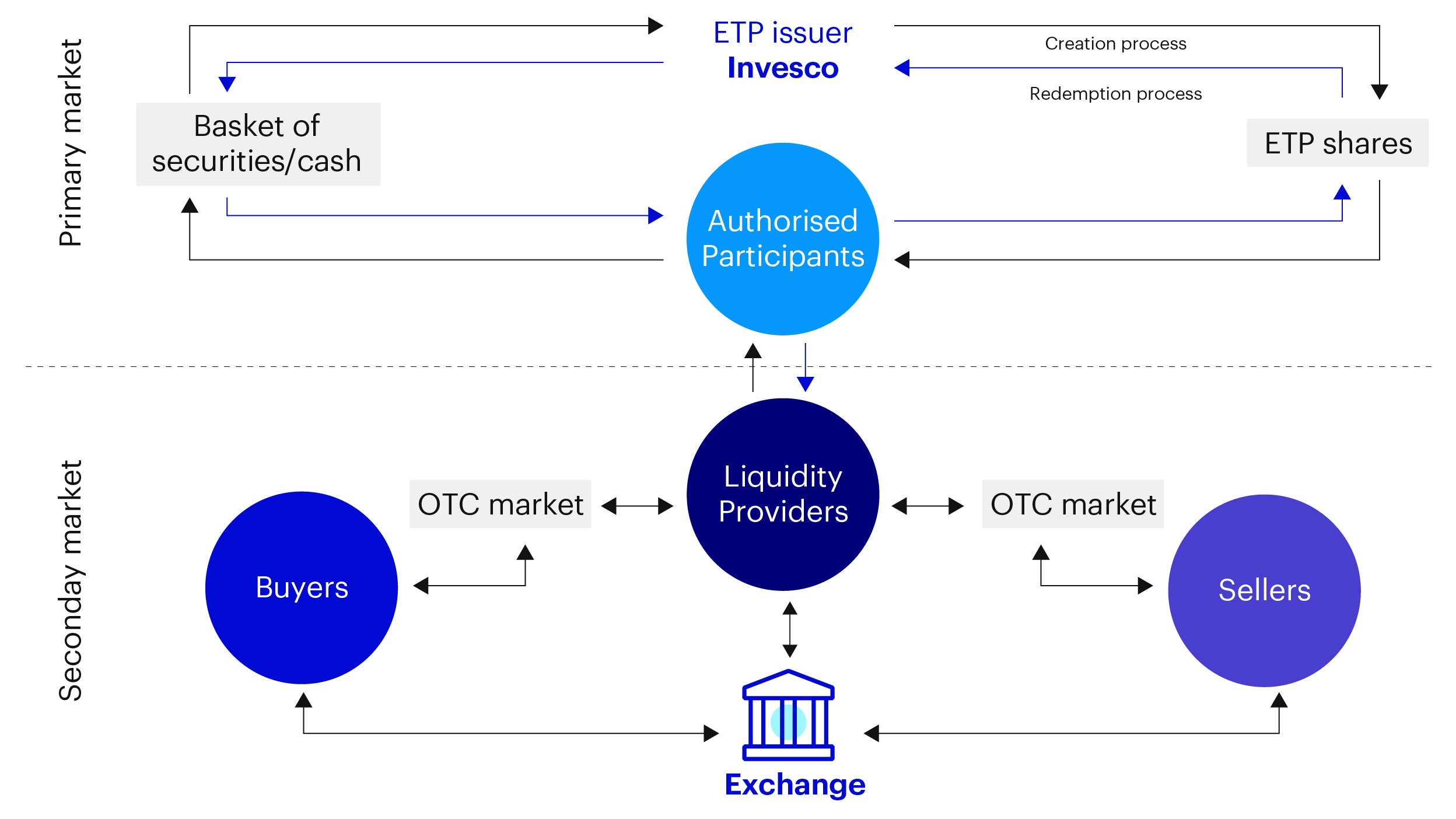

ETFs trade like a single stock on an exchange. At the same time, ETF shares can be created and redeemed in the so-called ‘primary market’ like a traditional mutual fund.

Investors can buy or sell ETF shares in the secondary market either on-exchange or over the counter (OTC). Only entities known as Authorized Participants (APs) (also known as Participating Dealers (PDs)) can access the primary market to create and redeem shares.

Liquidity, in its broadest definition, refers to how quickly or easily a security can be bought or sold for a price reflecting its worth. For single stocks, the market value can be defined as the price that someone is willing to pay for the stock in the secondary market depending on the supply and demand at different prices.

However, in the case of ETFs, the market value can be derived from the underlying basket of securities that the ETF is tracking. Within certain bounds, the ETF’s liquidity therefore originates from the supply and demand of the underlying basket and not so much of the ETF itself.

We will cover this in more detail in future articles on ETF arbitrage, premiums, and discounts.

This hybrid fund structure in design means that when it comes to liquidity, there are multiple layers and to support these multiple layers, there are multiple participants in the ecosystem. Visibility or perception of ETF liquidity, and the interactions with the providers of it are one of the most common misconceptions for new ETF investors.

Source: Invesco; for illustrative purposes only

The different roles of market participants and their interactions within the ETF ecosystem

Investors can only buy and sell shares in the secondary market. They cannot interact directly in the primary market of the ETF. The liquidity provided to the investors in the secondary market can come from:

- Natural buyers and sellers, i.e., other investors in the ETFs

- Liquidity providers (LPs) such as brokers, market makers and investment banks

Liquidity providers give prices to the market for shares to be bought or sold whether on an exchange or bilaterally (directly) to the investor OTC. These bid and ask prices are derived from the underlying baskets value and the various costs attached to that.

Visibly, investors can see the first layer of liquidity in the form of prices to buy and/or sell ETF shares on the exchange (known as average daily trading volume, ADV). However, much like an iceberg, there is a lot more liquidity below the surface in the primary market via the creation and redemption process.

Source: Invesco; for illustrative purposes only

APs are the only ones that can access the primary market through the create and redeem process. APs are typically large financial institutions with contractual agreements set in place with the ETF issuer allowing them to facilitate the process of creating and redeeming ETF shares. The entities themselves are usually investment banks or market makers who can also play a dual role in the secondary market as liquidity providers. As such, all APs are LPs, but not all LPs are APs.

The ETFs primary market mechanism and its relation to ETF price

The bid and ask prices that LPs show to the market to buy and sell ETF shares initially start with the valuation of the underlying basket.

If the value of an ETF is greater than the value of the underlying basket, then the ETF is said to be trading at a premium. If the price of an ETF is below the value of the underlying basket, then it is trading at a discount.

Let’s assume an ETF and the underlying basket is at $100. If the value of the underlying basket falls to 99 and the ETF remains at $100 (i.e., trading at a premium):

- An AP could buy the underlying basket for $99

- Deliver the basket (valued at $99) to the ETF issuer to create ETF shares (trading at $100)

- Sell the ETF shares at market price of $100

- Earn $1 in profit from the transaction

If the ETF falls to $99 while the underlying basket remains at $100 (i.e., trading at a discount):

- An AP could buy ETF shares at $99

- Redeem the ETF shares to the ETF issuer to receive the underlying basket

- Sell the underlying basket at market price of $100

- Earn $1 in profit from the transaction

The process described above is known as “ETF arbitrage”. This mechanism keeps ETF prices in between the bounds of transacting in the underlying basket. If the ETF did not have this primary market mechanism in place, investors may see the ETF price trading at steep premiums or discounts to the value of the underlying basket relative to the supply and demand of buyers and sellers in the secondary market, trading like a cash equity from a liquidity perspective.

Primary market, the market of ‘last resort’

When the demand for ETF shares outweighs the supply in the secondary market, APs can ‘choose’ to create shares directly from the ETF issuer. As supply outweighs demand in the secondary market, APs can ‘choose’ to redeem ETF shares to the ETF issuer. Ultimately, as long as the AP can effectively and efficiently trade the underlying basket of securities, these demand and supply imbalances can be adjusted continuously.

APs are motivated to play an active role in the ETF liquidity ecosystem as they can make a profit from these transactions. However, competition between dealers helps minimize the costs investors are likely to face on such commissions.

Whilst the primary market is always available, LPs will normally only interact in the primary market (directly as APs or indirectly via another AP) on a ‘last resort’ basis. If they do choose to interact in the primary market this means that they may pay the cost of what the ETF portfolio manager requires to replicate the index or investment strategy e.g., the underlying basket.

Source: Invesco; for illustrative purposes only

Instead, what LPs usually look to do is to offset or hedge the quantity of shares needed to satisfy the supply and demand imbalance by others means. This can be by:

- Using their own inventory/balance sheet

- Buying or selling the ETF shares in the secondary market themselves

- Using other correlated instruments futures, options, swaps, or other ETFs

- Borrowing or lending the ETF units

This would normally be more cost effective than paying the full bid/ask cost of the underlying. This cost saving in turn gets passed back indirectly to the secondary market in the form of tighter spreads. If it is not as cost effective, they still have the primary market available to them.

Final thoughts

This article provides a foundation as to how ETF liquidity is originated, who the market participants are, and the importance of the primary market in relation to the underlying basket and ETF price. In practice there are many other elements to an ETFs ecosystem which derives the valuation and costs associated with ETF trading. We will look further into this in future pieces.

For each ETF there are multiple market participants with bid and offers in the market, each of which wants the opportunity to match buyers and sellers. This competition makes execution very efficient for investors as each participant wants to show their very best price.

Each ETF has a different liquidity profile, and it starts from how quickly and easily the underlying basket can be bought and sold. It is important from an investor’s perspective that when choosing an ETF, the ETF issuer has a wide range of LPs and APs with different skill sets and backgrounds for the investment vehicle to operate as efficiently as possible. This support helps to enhance liquidity, reducing bid-ask spreads and thereby lowering the transaction cost of implementation to the investor.

Footnotes:

-

1

Global Fund Flows: After Record 2021 Inflows, 2022 Outflows Trickle Out, https://www.morningstar.com/views/blog/funds/global-etf-mutual-funds-disparity

-

2

Bloomberg, data as of March 31, 2023

-

3

ETFGI, data as of January 2023

-

4

ETF volumes hit record levels amid market turmoil, January 2022, https://www.etfstream.com/articles/etf-volumes-hit-record-levels-amid-market-turmoil