Understanding ETF trading and liquidity: Arbitrage, premiums, and discounts

In the first edition of our blog series we covered the basics of ETF trading and liquidity including the fact that fair market value can be derived from the underlying basket of securities the ETF is tracking. In normal market conditions, the price that an ETF is trading at in the secondary market will closely hug the fair value of the underlying assets. The primary market mechanism and the ability for market makers and liquidity providers to arbitrage away any discounts or premiums keep ETF prices close to the fair value – even in times of market stress or volatility.

In the second edition of this series, we assess premiums (when an ETF is trading at a higher price than its net asset value or NAV) and discounts (when it is trading at a lower price than its NAV). Investors can leverage premiums and discounts to engage in arbitrage or the simultaneous buying and selling of an asset in different markets to take advantage of differing prices for the same asset.

Last Price and NAV

Investors typically determine ETF premiums and discounts using the last price of the ETF versus the NAV. The NAV function on the Bloomberg terminal is a popular tool for this. However, without a correct understanding of why premiums and discounts may occur, there is room for misinterpretation using this method. To start with let’s look at how each valuation point is defined.

The NAV is the aggregate value of an ETF’s holdings less its total liabilities. An ETF can hold assets such as stocks, bonds, commodities, or even more recently digital assets such as Bitcoin. All these underlying assets are “valued” in a different way for the NAV calculation, such as last/closing price (equities), bid or mid-price at a specific time of day (bonds) or a fixing price (gold, which is usually determined at either 10:30am or 3pm UK time). An ETF’s liabilities are primarily the fees owed to the fund’s managing company.

To determine the NAV per share of an ETF for example, one could divide the fund’s overall NAV by the total number of shares issued at that moment in time. For example, the NAV of a Nasdaq 100 ETF would be calculated based on the closing prices of the underlying stocks on the Nasdaq exchange at that date.

Conversely the last price or last traded price of an ETF is normally derived at the closing auction of the ETF’s exchange order book. This price is based on the supply and demand dynamics of the ETF in the secondary market.

Taking the London-listed Nasdaq 100 UCITS ETF as an example, one common mistake investors make when assessing premiums and discounts is to compare the last price relative to the NAV, despite each occurring in separate time zones. In this case, the last price would have been calculated at the time of the London close while the NAV would be calculated based on the US close. In this scenario the timestamps on the valuations would not align and therefore it would be like comparing apples to pears.

Comparing the last price versus the NAV of a US-listed Nasdaq 100 ETF would be more appropriate, much like comparing the last price versus NAV of a London-listed FTSE 100 UCITS ETF. In both these cases the timestamps of the valuation points are aligned. However, the valuations can still be different based on the addressable liquidity available at the different points in time. We will address this further in a future article where we will cover the implications of liquidity for trading.

Intraday valuation

Most ETFs are required to disclose an estimated indicative NAV (iNAV) every 15 seconds throughout the trading day. This NAV is determined by an iNAV provider. There are many ways in which this could be calculated so investors should be cautious in using this figure as the sole reference point for execution.

For example, it may be the case that the iNAV provider is calculating in real-time a value for all the ETF’s individual holdings. But what happens when part of underlying basket is not open or tradable, such as the London-listed Nasdaq 100 UCITS ETF in the previous example? Does the price of that security remain stale? Are there proxies being used to incorporate an estimated value of what the security is worth? In fixed income it could be the case that one of the contributors of the underlying data is unable to submit a competent price due to a market event. Is this incorporated into the price shown correctly?

The main point here is that for an investor, the real-time value of an ETF is the price at which they can buy or sell the quantity of shares they are looking to trade. These prices are supplied by liquidity providers such as market makers and investment banks who are in many cases committing capital or risk to trade at that price. If their price is wrong, they bear the risk. However, these prices are kept in checks and balances through the ETF arbitrage mechanism.

The arbitrage mechanism

The market price of an ETF is governed and derived from the supply and demand of buyers and sellers in the secondary market. If there are more buyers than sellers, then the price of the ETF will be pushed up (like an equity security). If there are more sellers than buyers, the price of the ETF will be pushed down. When either happens the market price of the ETF could be dislocated from its NAV, creating a premium or discount, and importantly, an arbitrage profit opportunity for authorized participants (APs).

This opportunity, which is specific to ETFs, plays a crucial role in ensuring a close relationship between an ETF’s share price in the secondary market and the value of the securities held within the ETF portfolio. When the ETF share price deviates from the fair value of the portfolio securities, APs can step in to arbitrage the difference. However, if obtaining current prices becomes challenging, the premium or discount may persist in the ETF.

Why do premiums and discounts occur in fixed income ETFs?

Typically, fixed income ETF NAVs are calculated based on the prevailing mid or bid prices of all the underlying bonds. When comparing two ETFs, the pricing methodology of the NAV of each ETF must be known in advance to compare apples with apples.

On any given day, you should expect a mid-marked NAV fixed income ETF to trade at a relative discount to a bid marked NAV ETF by a factor of half of the underlying market bid/ask spread. Furthermore, the underlying market bid/ask spread is not static and will widen/tighten in varying market liquidity conditions.

In a bid-marked NAV ETF, if buyers outweigh sellers on an exchange, the ETF price should trade at an expected premium of the full underlying market bid/ask spread. This is because as buyers outweigh sellers, liquidity providers would need to create shares of the ETF and buy bonds at their offer prices to deliver into the portfolio to facilitate said creation. Conversely, if sellers outweigh buyers on exchange in a bid-marked NAV ETF, the ETF price should trade in line with NAV as liquidity providers should be able to redeem the ETF shares, take the bonds they hold and sell them at those bid prices.

It is important to note that bonds are traded over the counter and may trade infrequently – sometimes not for days or weeks. In fact, according to a 2018 SEC bond market liquidity study, only 20% of corporate bonds trade on any given day.1 Thus, in normal market conditions, NAV pricing agents must ensure a significant portion of the fixed income ETF portfolio is at fair value to calculate the daily NAV.

If a bond does not have a recent round lot trade, pricing agents may source indications from bond dealers, providing an assessment of the bond’s value on that day. This can be effective if those indications are consistently updated and are in fact actionable prices.

However sometimes we see stale or outdated NAVs for the underlying portfolios of bond ETFs. So, while premiums and discounts may happen, these may simply reflect investors using bond ETFs for price discovery rather than trading the underlying individual bonds. Again, the ETF share price is more “current” than the NAV.

What can investors look out for?

Recent headlines coming out of China have highlighted situations where significant premiums have occurred in China A-shares ETFs. These occurred as the QDII quota limit was reached thus adversely affecting the underlying basket of securities on the primary market. In this case the ETF behaves more like a closed-end fund where no more shares can be issued. The market price therefore becomes reliant on supply and demand in the secondary market as the primary market ETF arbitrage mechanism is not actionable.

We’ve seen other occasions where the underlying market has closed for an extended period whilst an ETF has continued trading. One example was in the summer of 2015 during the Eurozone debt crisis where the Athens Exchange was closed for several weeks. During this time, ETFs tracking the Greek market became the instrument of price discovery for traders. When stocks listed on this exchange reopened, they did so at prices relative to where the ETFs had been trading.

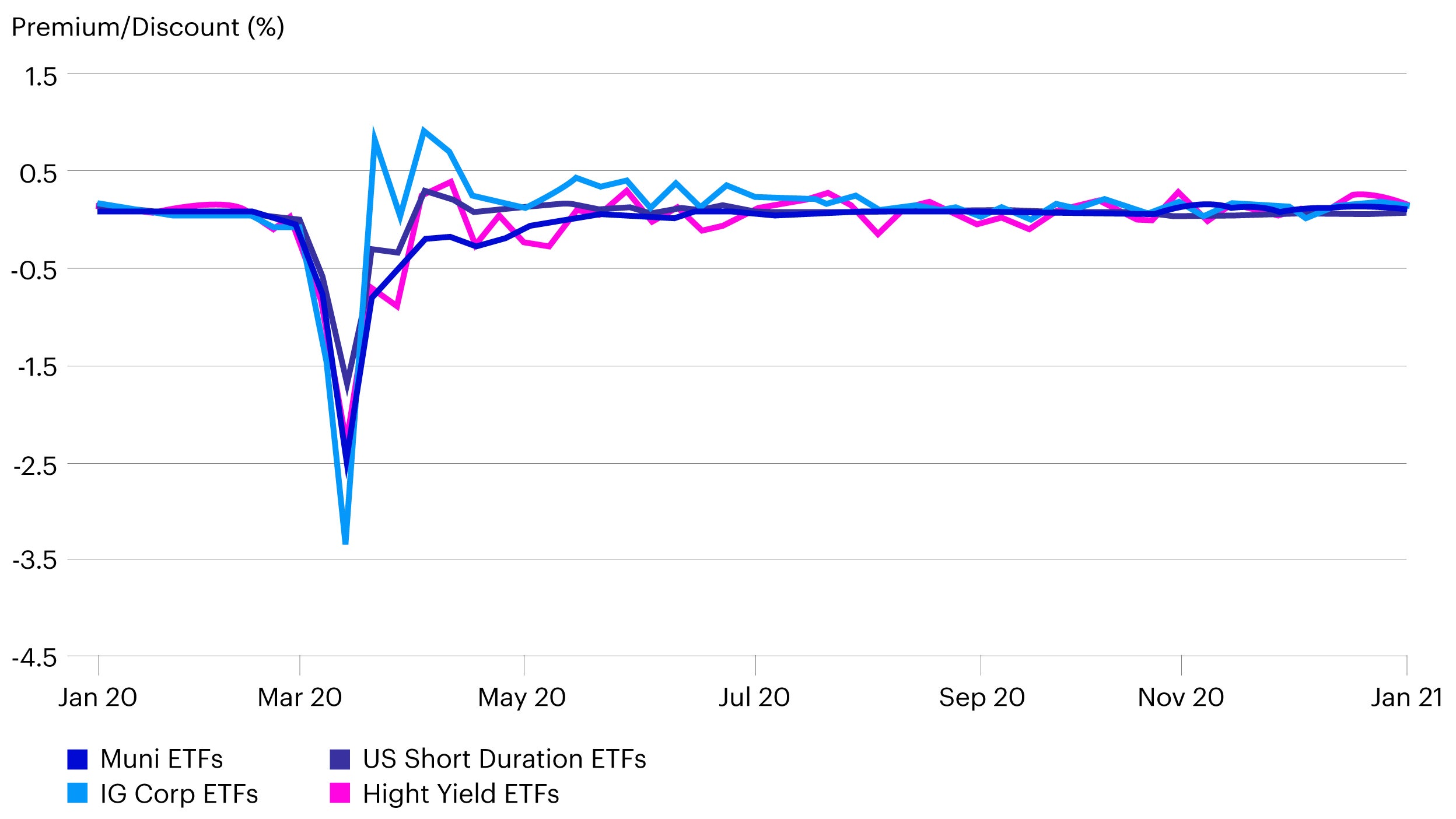

During the high period of volatility arising from the COVID pandemic in 2020, the average discount to NAV for investment grade corporate bond ETFs reached 3.4% in mid-March, with some products even witnessing discounts greater than 8%.2 Given that ETFs are traded in a free market and bound by arbitrage, it is fair to assume that if an ETF’s price is too high versus its underlying basket, liquidity providers would have redeemed and arbitraged away the discount to NAV. If these products’ NAV prices were actionable, and market makers could sell these bonds at prices substantially higher than the ETF price in the market, the dislocation would have been normalized immediately.

Source: Bloomberg, data as at December 2020.

To summarize, premiums and discounts to NAV may happen in ETFs, but it’s important for investors to realize why they are happening and that they may not reflect an operational shortcoming by the ETF itself.

One of the most common questions investors ask about ETFs is how they hold up in times of stress and volatility. Our conclusion is that not only have ETFs proved resilient during real life stress tests, but that investors recognize and value the liquidity that these investment vehicles provide for their portfolios.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding the dynamics between the last price and NAV of ETFs is crucial. The NAV represents the intrinsic value of an ETF’s holdings minus liabilities, calculated using various valuation methods depending on the asset class. Conversely, the last price reflects the market’s supply and demand forces at the close of trading. Discrepancies between these two figures can lead to premiums or discounts, which may not always indicate mispricing but rather differences in valuation timestamps, liquidity, or market conditions.

We believe that while the intraday indicative NAV (iNAV) offers a more frequent valuation, it should be approached with caution due to potential discrepancies during non-trading hours of the underlying assets. The arbitrage mechanism plays a pivotal role in aligning the ETF’s market price with its NAV, allowing authorized participants to capitalize on price deviations for profit, thereby ensuring market efficiency.

However, in the realm of fixed income ETFs, premiums and discounts can arise due to the less frequent trading of bonds and the reliance on fair valuation by pricing agents. These deviations often reflect the market’s use of ETFs for price discovery, emphasizing the importance of understanding the underlying pricing methodologies and market mechanics to make informed investment decisions.

It is also important to understand that ETF premiums and discounts can arise from market anomalies or regulatory limits, such as the QDII quota in China, which can prevent usual arbitrage mechanisms from functioning. These situations can cause ETFs to behave like closed-end funds, with prices driven solely by secondary market supply and demand. Historical events like the Eurozone debt crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that ETFs can become primary instruments for price discovery when underlying markets are closed or volatile. It’s crucial for investors to understand that such premiums and discounts do not necessarily indicate ETF inefficiencies but are often a reflection of market conditions and liquidity. Overall, ETFs have demonstrated resilience in times of market stress, and are a valuable source of liquidity for investors’ portfolios.