ESG investing: From exclusion towards transition

Key takeaways

Although environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing has come a long way, the broad feature of static exclusionary lists is showing its limitations as we enter a new phase of ‘ESG 2.0+’.

We believe an investment strategy based on low-carbon transition is the best approach. Our new methodology seeks to maximise the benefits of transition investing whilst minimising the challenges.

The approach focuses on high carbon emitters today, their ability to fund their transition and willingness to allocate the necessary capital to achieve this. At the same time financial returns are considered.

As Fund Managers, we’re seeing first-hand how ESG is evolving and how the regulatory environment is changing. We continue to monitor what these trends mean for the asset management industry.

The evolution, so far, has led to the launch of various types of ESG-based investment strategies. But there is one predominant feature across many of the strategies: static exclusionary lists. Excluding companies because they emit high levels of carbon today means shunning businesses capable of reducing their emissions going forward. While static exclusion strategies have generated many positive benefits for both sustainability-focused investors and society, they have significant limitations.

We believe the way to overcome these is to focus on a combination of ‘carbon emissions materiality’ and transition. This forward-looking approach, in our view, provides a mechanism for investors to allocate capital to industries and companies that can be part of the environmental solution, as opposed to merely focusing on the companies that are already outside the scope of the issue. This is the essence of our approach.

The changing regulatory background creates space for transition funds

Investors have been slow to react to new regulations, many of which acknowledge the importance of highly emission intense industries in transitioning to a low carbon society. To achieve ‘the transition’ requires companies to decarbonise their activities or, re-orientate where decarbonisation is not possible, according to the November 2022 report from the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF). Regulators are putting more emphasis on changing the status quo. This, we believe, shows the direction of travel for ESG regulation: From exclusion towards transition.

The key benefit of transition is that it promotes engagement with high-emitting companies, rather than ignoring them. The forward-looking nature of transition strategies produces challenges, such as data and monitoring success, but these obstacles can be overcome through building a robust investment process. We believe building the right transition framework allows asset managers to build truly sustainable funds combining strong decarbonisation whilst maintaining financial objectives.

Investment decisions are inherently forward looking. As such, investors shouldn’t base decisions only on past and current greenhouse gas emissions, but the forward-looking transition plans. This is how the investment community can help the world.

Cue the next generation of sustainable investing: TRANSITION. It’s a different strategy that will reward a different group of stocks. It involves engaging with the large emitters – not excluding them.

Steve Smith – Fund Manager, European Equities

The evolution of ESG funds

ESG has evolved significantly over the past decade. This has led to a plethora of different types of funds for investors to choose from. The table below shows the AUM growth in several ESG strategies in recent years.

Classifying Global Sustainable funds into ESG 1.0 & ESG 2.0

($ Billion)

Invesco Classification |

Approach |

2016 |

2018 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ESG 1.0

|

Negative/exclusionary |

15064 |

19771 |

15030 |

Norms-based screening |

6195 |

4679 |

4140 |

|

ESG 2.0

|

Positive/best in class screening |

818 |

1842 |

1384 |

Sustainability themed |

276 |

1018 |

1948 |

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance 2021. From the Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. We have excluded some types of ESG funds in the above table including Impact/Community Investing, Corporate Engagement & Shareholder Action and ESG Integration.

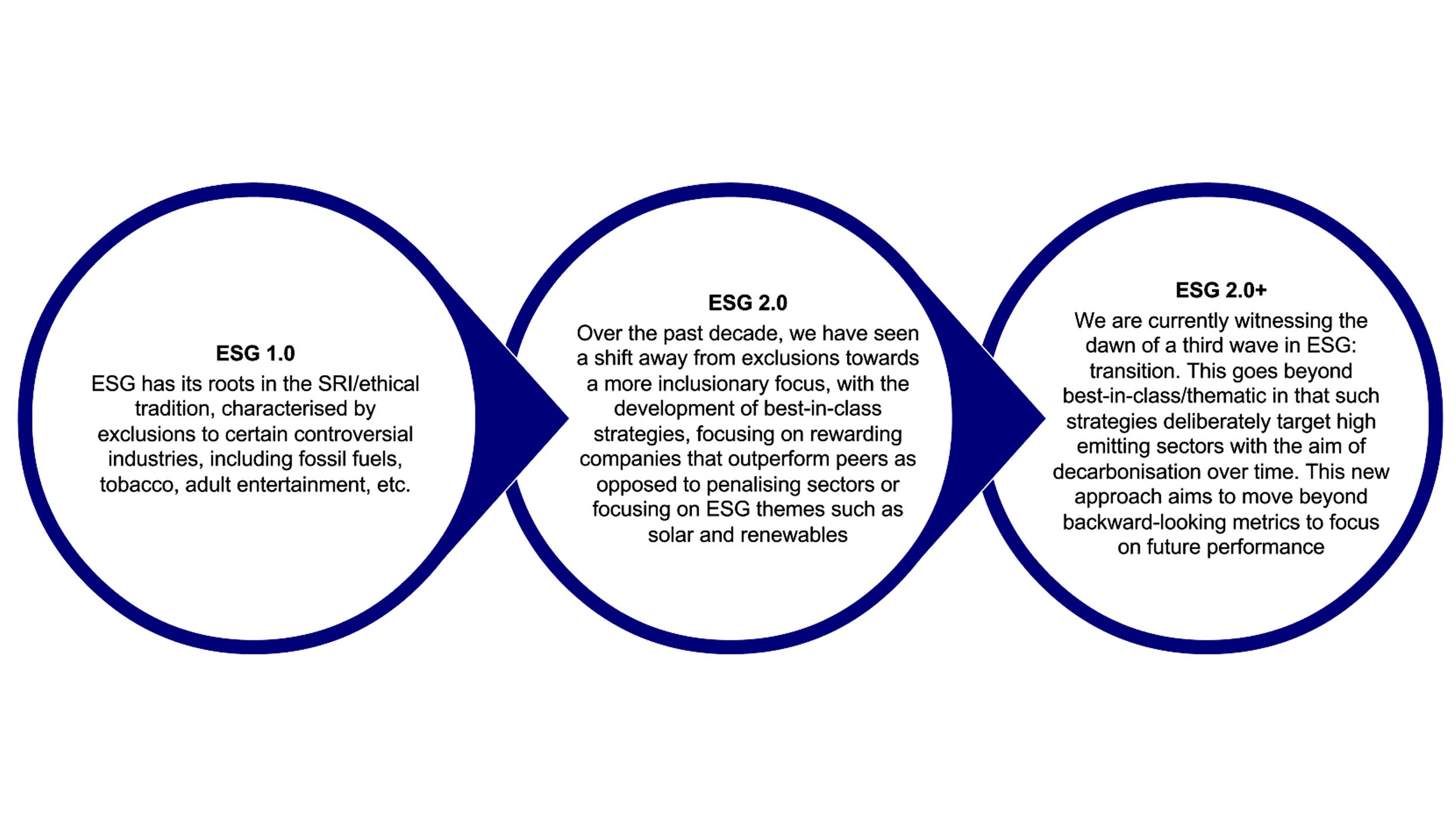

For simplicity, we’ve segmented the evolution of ESG funds, as shown in the table above, into specific phases. We call these phases ESG 1.0 and ESG 2.0. Today, we believe we are moving into a new phase that we’ll refer to as low-carbon transition or ESG 2.0+. This next phase requires a different approach and will see funds with starkly different holdings than those that emerged during the first two waves.

These first iterations of ESG investing had an important role. They forced management teams and investors to embrace ESG and empowered regulators. They financed the growth of new industries and companies that are instrumental for the fight against climate change.

But there were unintended consequences. Capital markets’ primary role is capital allocation. Those seen as the ‘best’ ESG companies have higher multiples or lower cost of equity. Those considered the ‘worst’ ESG companies have the reverse.

This static exclusion approach rewarded a relatively concentrated number of companies at the expense of the remainder. In effect, this incentivised companies to divest 'brown’ assets, which did nothing to address the fundamental issues of reducing carbon emissions. It merely forced those assets into private markets/ownership, an area less scrutinised.

At worst, we believe static exclusions impeded emission reduction. Companies, industries and even entire regions were starved of capital. Decarbonisation requires capex. Being starved of capital has likely hindered the ability to invest and decarbonise and instead instilled a culture of buying back cheap equity or expensive debt rather than investing.

Energy companies epitomise static exclusionary strategies. In April 2021, Morningstar undertook an extensive survey of Climate Aware funds, noting: “For many asset managers, fossil fuel has become part of a broader exclusion list, in additions to weapons, tobacco and other controversial activities. Moreover, definitions of fossil fuel exclusions tend to vary greatly, from the simple exclusion of companies involved in thermal coal generation to no investments in companies with fossil fuel reserves or any involvement in fossil-fuel-related activities, including exploration, production, and distribution.”

Such a reaction was understandable, as the sector was an easy target. It was working through a period of weak fundamentals and, directly and indirectly, contributed to a large percentage of global emissions by producing the materials that we combust when traveling, transporting or heating property.

Oil and gas also epitomise the unintended consequences of static exclusion lists. Energy companies were implicitly told by capital markets to stop investing in hydrocarbons. This built the foundations for the tight global energy market we see today, which, has resulted in a lack of energy supply in Europe. The consequence being an increase in coal-based power generation in several European countries in 2022.

We believe the shortcomings of the existing approach to ESG investing means another approach is required if we’re to successfully mitigate climate change. We need a more holistic approach to reducing emissions within high emission sectors rather than ignoring them.

Why low-carbon transition is a better approach…ESG 2.0+

The term ‘transition’ is a broad term, referring to a company or sector’s projected journey from its current business model to a different one. This should include the changes a business is making to help mitigate climate change and how business models are adjusting from a fossil fuel-based economy to the 'low-carbon economy’. For most businesses, it’s neither easy nor an overnight process. It takes significant management and financial resources to be successful.

Forward looking makes for better engagement

The transition approach is more dynamic and forward looking than previous iterations of ESG investing. It not only assesses carbon materiality today, but more importantly, where it can be in the future.

Investment decisions are inherently forward-looking. As such, financial market participants should not be assessing the past and current state of companies’ greenhouse gas emissions, but the transition plans associated with pledges to reach net zero. By analysing the transition plans of specific companies, we can assess the likelihood of success but also the impact it has on all stakeholders. The approach allows investors to identify those companies who can achieve their decarbonisation plans in a way that is fair for all stakeholders, especially important when the bulk of the efforts are in the medium to long term.

Such an approach also allows investors to identify those companies who, in their current guise, are not able to reposition their business for a low carbon society. Or those companies who have plans that are heavily skewed towards certain stakeholders, at the cost of others. These businesses can be engaged with proactively.

Once we start looking forward, we can have meaningful engagements with large emitters, not exclude them, and in so doing actively encourage change. Focus, therefore, should be specifically towards the large emitters not against them. We must embrace the reality that we need to pass through different shades of ‘brown’ before reaching the ‘greener’ pastures of a low carbon society.

Abatement has second-order effects

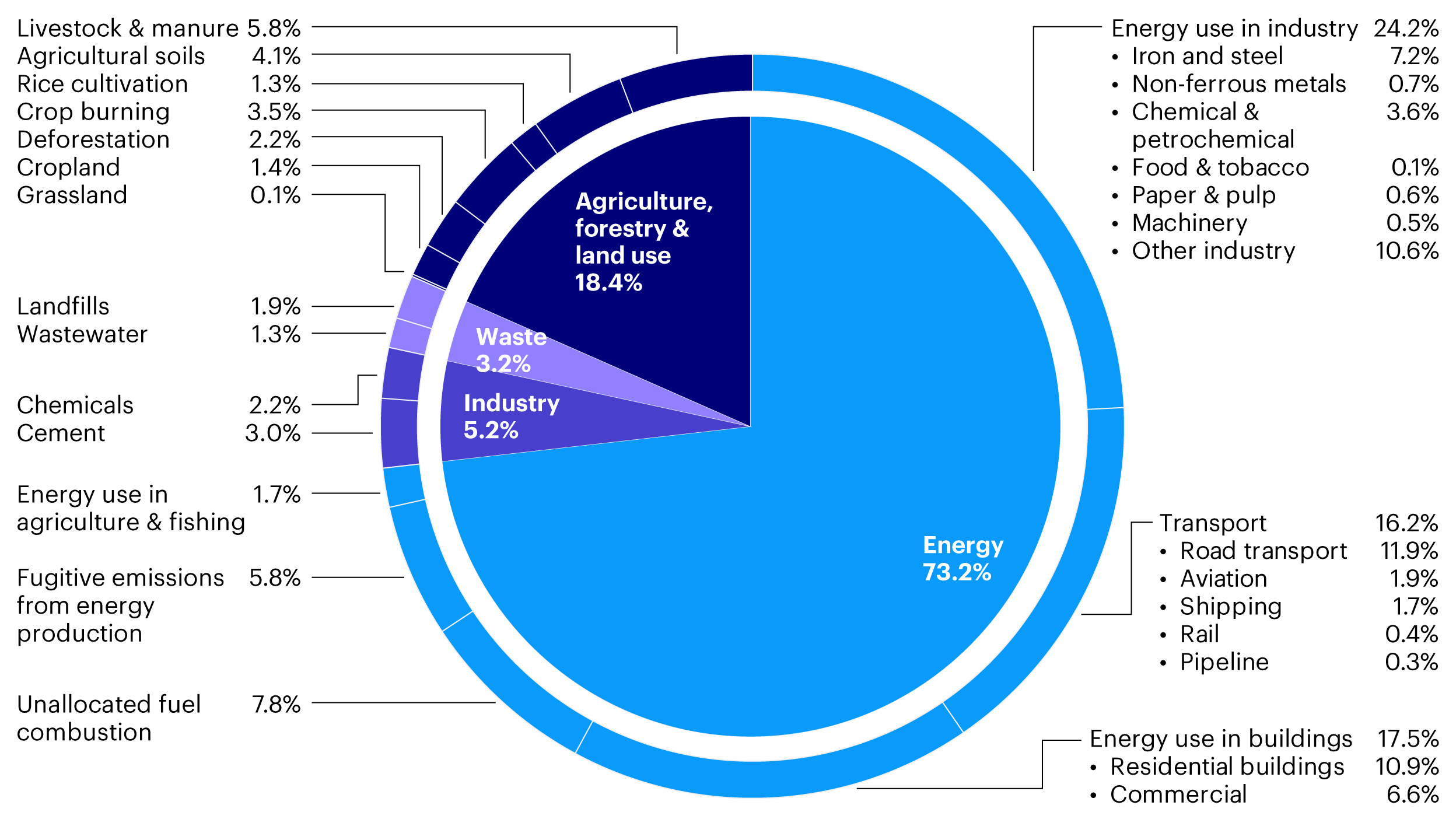

In our opinion, to date, more emphasis has been put on, and more investment capital directed to, emission prevention rather than emission abatement. For example, funding the creation of low carbon energy supply rather than funding the closure of high emission energy supply. We feel the latter has a positive multiplier effect on emission reduction further down supply chains and should therefore be seeing capital flows. Most emissions can be linked to upstream activities. The opportunity, or challenge, is shown below.

Shown for the year 2016 – global greenhouse gas emissions were 49.4 billion tonnes per CO2eq. Source: Our World in Data; Climate Watch, the World Resources Insitute 2020 (data shown at 2016).

Achieving positive second-order effects: The faster we can decarbonise heavy industries, the better, due to the positive knock-on effect. Making cleaner raw material inputs makes it possible to decarbonise downstream products. For example, we should be rewarding a steel production company for building green steel capacity. This would allow a truck manufacturing company to make fossil free electric trucks. An investment banking company Post would in turn be helped in efforts to decarbonise its logistics offering. Without the creation of green steel, the latter two cannot fully decarbonise their activities.

Avoiding negative second-order effects: Decarbonising base materials is integral to avoiding negative knock-on effects. The overall energy transition requires significant investment. It requires all parts of global supply chains to invest cash. This capex will increase demand for commodities and energy. Therefore, it is imperative we can extract commodities and produce energy in a low emission intensive way. If we exclude and ignore these sectors, decarbonisation capex elsewhere will be increasing upstream emissions. Divesting these sectors – pushing them from public to private markets – will not help the world move to a low carbon world.

The benefit to investors: linking transition and financials

We have conviction that transitioning heavy emitters has the greatest impact on emission reduction. Importantly, we also believe it’s a way to combine sustainable and financial objectives.

As discussed, we believe investors can make the largest contribution to mitigating climate change by owning, and therefore supporting, high emitters to decarbonise. Owning a portfolio of low-emitting business models that can easily get to net zero does little for society from a carbon reduction point.

Carbon materiality is the key to linking sustainability and financial objectives. For example, a steel production company and therefore a material emitter today, could drastically improve their financial returns if they built a differentiated position in green steel. It has the potential to improve their revenue, as green steel has a higher average selling price and margins and lower their costs long term through reducing their carbon credit liability.

Furthermore, there are steel companies that either don’t have the ability, or willingness to transition to fossil-fuel free steel. This differentiation will cause creative destruction – companies that can’t afford capex will cease to operate. Companies that successfully evolve their businesses will enjoy a period of supernormal profits.

By identifying leading companies in hard-to-decarbonise sectors, investors can pick long term winners. This allows the combination of financial and sustainable objectives, a key positive of transition investing. We have set out the many positives associated with low-carbon transition, but there are some challenges in its implementation.

Transition investing faces several issues

Varying speeds of transition

The speed of transition required, by industry, company and even country, varies significantly. The chart below demonstrates current expectations for how various high-emitting sectors will decarbonise. This is an important consideration, as slower transitioning sectors risk losing out to faster transitioning sectors as capital flows seek the quickest wins.

Source: IEA. Note: Other = agriculture, fuel production, transformation and related process emissions, and direct air capture.

In addition, the transition cost varies greatly between sectors due to project economics, competition and technology. For capital markets to fully embrace the slower and more costly transition stories, we’ll need policy makers to establish supportive and stable policy frameworks, regulatory regimes and incentives.

Fortunately, we’re seeing positive momentum here. The EU has just recently, significantly increased the ambition of its EU Emissions Trading System to cover more heavy industries. The fact that this comes despite a backdrop of an unprecedented energy crisis, acute cost-of-living pressures, and a land war in Europe, clearly demonstrates the EU’s commitment to remaining a global leader in the fight against climate change.

We’re also encouraged by the increased funding from governments. In Europe, the EU Recovery Fund in conjunction with the EU Green Industrial Plan, is making more money available for investment. Likewise in the US, the introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act, should be supportive for decarbonisation.

With a supportive regulatory backdrop, combined with greater funding, the attention can move to the other key issues, like data availability and performance monitoring.

Data challenges

A big issue in low-carbon transition investing is the availability of emissions data, especially Scope 3 data.

Some advocate ignoring Scope 3 as the reported company data is inconsistent or non-existent. We disagree. Scope 3 emissions make up the majority of total emissions for most sectors. Ignoring it gives companies the ability to ignore their hardest emission challenges.

It’s important to remember that most business models are reliant, indirectly, on ‘dirty’ materials or energy sources still, which are a big source of Scope 3 emissions and are often linked to operations in other parts of the world. Not acknowledging these Scope 3 emissions or the geographic mismatch between consumption and production would be wrong.

Scope 3 data is still in its infancy but is moving in the right direction and therefore we believe it is valid for investors to focus on Scope 1 + 2 + 3 emissions. Including Scope 3 in analysis and engaging with companies on it helps to improve emissions reporting and the ability of investors to fully map companies to their emissions.

Monitoring companies on their transitions

There is huge interest on the part of many stakeholders to understand how to set robust transition targets and strategies, and to evaluate those set by others. After all, the investment community’s focus on sustainability is rooted in a fiduciary duty to clients. As set out earlier, we believe failing to transition will hurt a company’s financials and therefore underlying value. Investors need to monitor the progress of companies’ transition plans.

As stewards of capital, we believe that companies shouldn’t be allowed to simply set long term targets and move on. However, we acknowledge that monitoring structural emissions reduction is complex.

There are four things that can change a company’s reported emissions:

- The macroeconomic cycle (e.g. volumes)

- Emissions calculation (i.e. methodologies)

- Corporate actions (e.g. disposals)

- Structural changes.

Only the latter should be rewarded or punished, in our view. This is where fundamental investors can add value.

Fundamental analysis and engagement allow investors to make forward-looking emissions estimates and assessments on the likelihood of a company’s transition. Transition strategies need to be run actively and proactively. We need to adapt analysis to account for the economic cycle: mechanically CO2 emissions go up with GDP and vice versa. In-depth analysis of a company’s transition plans allow investors to estimate their likelihood of success, but equally as important it allows for a better understanding, either at issuer or fund level.

Our transition philosophy: overcoming challenges

Our overall sustainable objective is mitigating climate change in a fair and conducive way for all stakeholders. We believe pursuing an investment strategy based on low-carbon transition is the best approach to deliver on this objective. We have built a methodology that seeks to maximise the benefits of transition investing whilst minimising the challenges.

We’ll focus on carbon materiality but expand the analysis into the issuer’s ability to fund their low-carbon transition and willingness to allocate the necessary capital to achieve this. Our assessments of carbon materiality, ability and willingness will be based on available third-party data but combined with our proprietary models and direct engagements with the company. We feel this improves the quality of our inputs and allows for better forward-looking analysis. These data sources also improve our capabilities in monitoring companies’ success and reporting the aggregate decarbonisation at a fund level. We strongly feel our approach will positively contribute to the growth in transition investing, which in turn will help push our society towards a low carbon future.

Overall, our process requires a deep understanding of companies’ targets and strategies. We will draw upon our active, long-term and fundamental stock analysis to assess transition strategies of the companies we will consider owning. Our traditional active investment process, combined with team experience, provide us with the necessary skillsets to identify businesses that can improve their competitive positioning and fundamentals as they change for the better.

Our goal is to invest in businesses that can thrive, not just survive, as they transition.

FAQs

Asset managers, banks and other market participants use a screening process to ascertain whether certain companies should be excluded from the investment process. The screening criteria is usually based on international standards, norms and/or laws. Examples of exclusions include companies that derive a certain percentage of their revenue from thermal coal extraction or from coal energy. Other exclusions include the producers of certain types of weapons and harmful products such as tobacco; companies with governance issues; or those that engage in practices such as child labour.

If environmentally friendly investments are called 'green', money used to finance high-emitting industries is sometimes called 'brown' financing. This could include fossil fuel producers, among others.

Net zero refers to a state in which human-made emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) going into the atmosphere are balanced by removals out of the atmosphere, over a specified period. The ‘net’ in net zero is important because it will be difficult to reduce all emissions to zero on the required timescale. As well as deep and widespread cuts in emissions, there will likely be a need to scale up GHG removals. The Paris Agreement underlines the urgency of net zero, requiring states to aim to limit global warming to well below 2°C and preferably to 1.5°C.

Scope 1 covers emissions from sources that an organisation owns or controls directly. Scope 2 are emissions that a company causes indirectly when the energy it purchases and uses is produced. Scope 3 encompasses emissions that are not produced by the company itself, and not the result of activities from assets owned or controlled by them, but by those that it’s indirectly responsible for, up and down its value chain.