ESG & Impact: Investing for Climate Adaptation in Asia

In this podcast, Norbert Ling, ESG Credit Portfolio Manager, Alexander Chan, Head of ESG Client Strategy, Asia Pacific and Yifei Ding, Senior Portfolio Manager examine the investment themes and challenges of impact investing and climate adaptation in Asia.

This is the second of a 2-part series focused on impact investing in Asia. Part 1 gives an overview into impact investing opportunities and challenges, while Part 2 deep-dives into impact investing for adaptation.

As shared in our ESG Outlook, much of the global discourse and initiatives on ESG previously focused on climate mitigation (i.e., focusing on reducing emissions) such as thinking about net zero commitments and transition pathways. Yet coming out of COP27, climate adaptation has increasingly grown in interest. This piece examines the case for investing in climate adaptation in Asia, including understanding adaptation needs and providing an approach for impact investing.

Climate adaptation overview

Climate adaptation overview

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines adaptation as “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects”1. This includes adjustments to environmental changes that have occurred as well as increasing resilience to minimize potential climate risks in future. Key considerations relating to adaptation include:

- Wide impact: Adaptation affects both natural ecosystems (like ocean) and human systems (like food, health). Magnitude of impact is dependent on the region and sectors in concern.

- Localization: Analyzing impact of adaptation needs to be done at localized level given differing types and degree of impact across regions.

- Maladaptation: Refers to unintended effects of adaptation efforts that may cause more adverse climate outcomes such as reinforcing socioeconomic disparities or redistributing vulnerability from one region to another or causing new sources of vulnerabilities2.

- Limits to adaptation: Increases in warming and temperature further constrains effectiveness of adaptation. IPCC also warns that adaptation limits exist where there would be risks where adaptation options might not be available.

- Notable developments in climate adaptation over 2022 have helped increased global attention on adaptation, this includes:

- IPCC AR6 WGII: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II report released in 2022 focuses on “impacts, vulnerability and adaptation” emphasizing on the importance to consider adaptation solutions amidst increasing physical risks

- COP27: The Sharm-El-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda3 was launched outlining 30 adaptation outcomes to enhance resilience for most climate vulnerabilities by 2030 including areas relating to food security, water and nature, human settlements systems, ocean, and coastal systems. The Adaptation Fund also received more than $240M USD4 in new funding and pledges.

- COP15: Global biodiversity framework launched at Biodiversity COP15 included a target focused on minimizing impact of climate change on biodiversity including contributing to adaptation through ecosystem-based approaches5.

Why Asia matters for climate adaptation

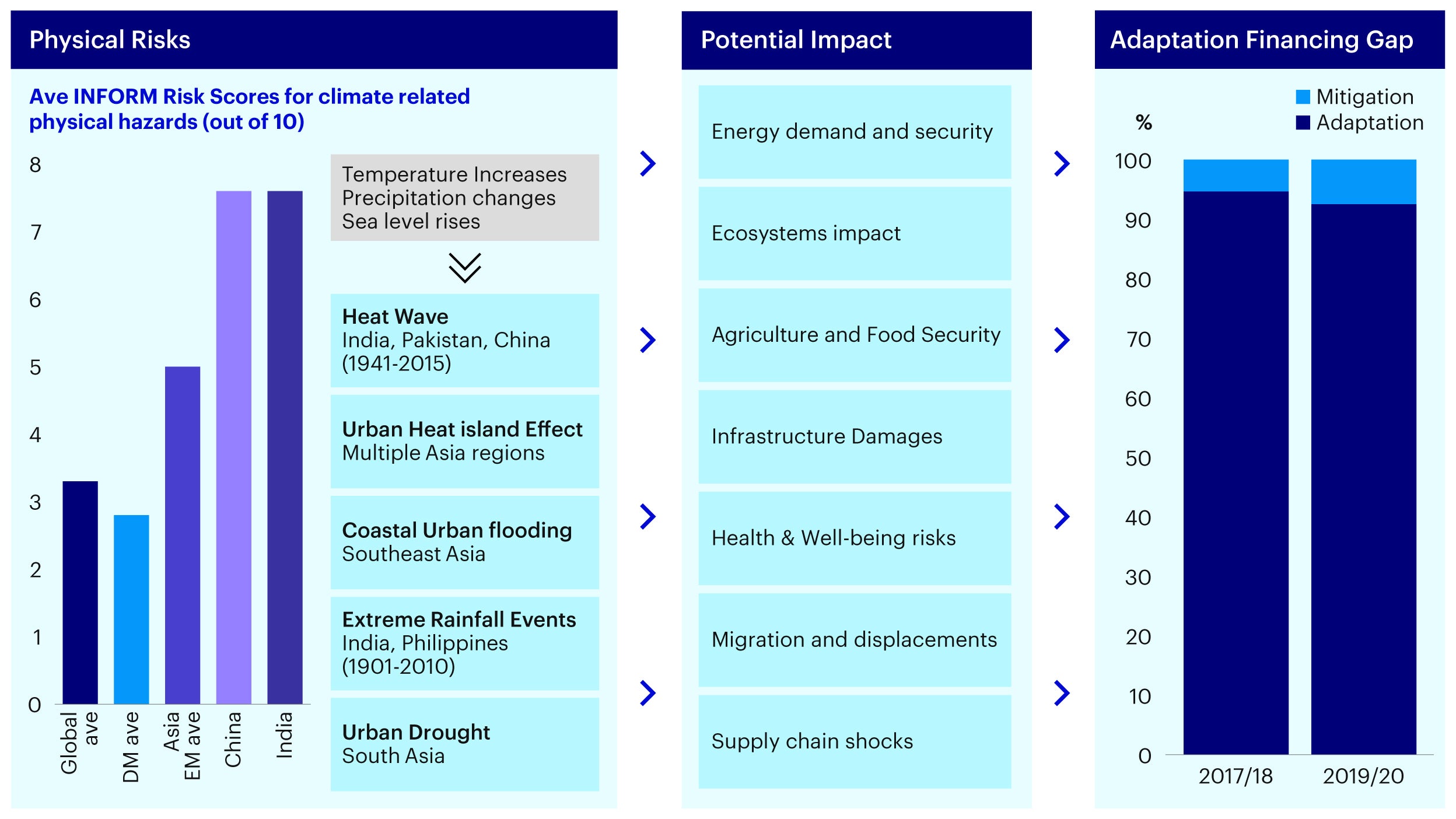

Source: INFORM Scores; Morgan Stanley Research; OECD Landscape Climate Finance; IPCC AR6 WGII; Invesco Analysis.

Asia’s geographic positioning along with the state of socioeconomic development increases the magnitude of climate adverse impacts and raises the need for climate adaptation. Key drivers of why Asia matters include:

- Physical risk impact in Asia: Asia as a region is particularly vulnerable to physical risks relative to other APAC regions with historically much higher occurrences of weather disasters. The larger population alongside low existing adaptive readiness also means that risks in terms of financial or social impacts are more significantly felt. IPCC’s research6 has shown that climate drivers of temperature increases, precipitation changes, sea level rises have in turn also driven more acute climate changes such as heat waves, droughts and flooding and biodiversity and habitat loss.

- Socioeconomic impact: In turn the physical risks translate into potential sectoral and socioeconomical impact

o Increase in energy demand: Climate changes increase energy consumption (such as for heating or cooling) adding pressure on infrastructure and capacity. This is especially as Asia is one of the largest energy importers and material energy security risk and self-sufficiency is expected to decrease from 72% to 63% by 20507.

o Ecosystems impact: Impact on biodiversity and habitat of animals and plants are common risks linked to climate changes. Changes to species distribution due to warming stress, irreversible losses of marine and coastal ecosystems and increasing water stress.

o Agriculture and food security: Precipitation changes and droughts alongside temperature increases affect crop productivity, livestock mortality and affects incidence of pests and diseases. Asia in particular accounts for 67% of global agriculture production and food supply could see significant yield declines.8

o Infrastructure damages: Physical hazards and extreme weather events like droughts, earthquakes and cyclones have previously led to annual multi-hazard losses of more than $170B USD within Asia9 impacting power, water, and other built infrastructure.

o Health and well-being risks: Exposure to climate variations and adverse events could also increase health risks given air pollutants, water-borne diseases, and heat stress. World Health Organization (WHO) estimates around 250,000 deaths per year from 2030 to 2050 including from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea caused by climate changes; particularly in South, East and Southeast Asia.

o Migration and displacement: Climate migrants from South Asia are projected to amount to 40 million by 2050 (1.8% of the regional population)10 producing potential demographic changes and strains in resources.

o Supply chain shocks: Various impacts above could also lead to supply chain shocks and dislocations especially when adverse weather events impact production and logistics.

- Adaptation financing gap: Given the impacts and risks, significant financing is needed towards adaptation needs. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that annual adaptation costs in developing economies would be near $155-300 billion USD by 203011. Yet most of climate finance has gone predominantly into mitigation and adaptation financing still falls behind. There are significant opportunities for investing into adaptation.

- Separately, the physical impacts laid out earlier could also have material financial implications, including:

- Maintenance capex: Higher capex could be expected in sectors with heavy assets given potential climate impact.

- Productivity changes: Adverse weather events likely to impact both workforce productivity and production capacity.

- Costs inflation: Supply shocks from weather disruptions could also drive costs inflation both in supply inputs and end consumables.

- Insurance premiums: Higher insurance premiums are expected especially in sectors with risks of stranded assets.

Challenges to investing for climate adaptation

Source: Invesco analysis, for illustrative purposes only.

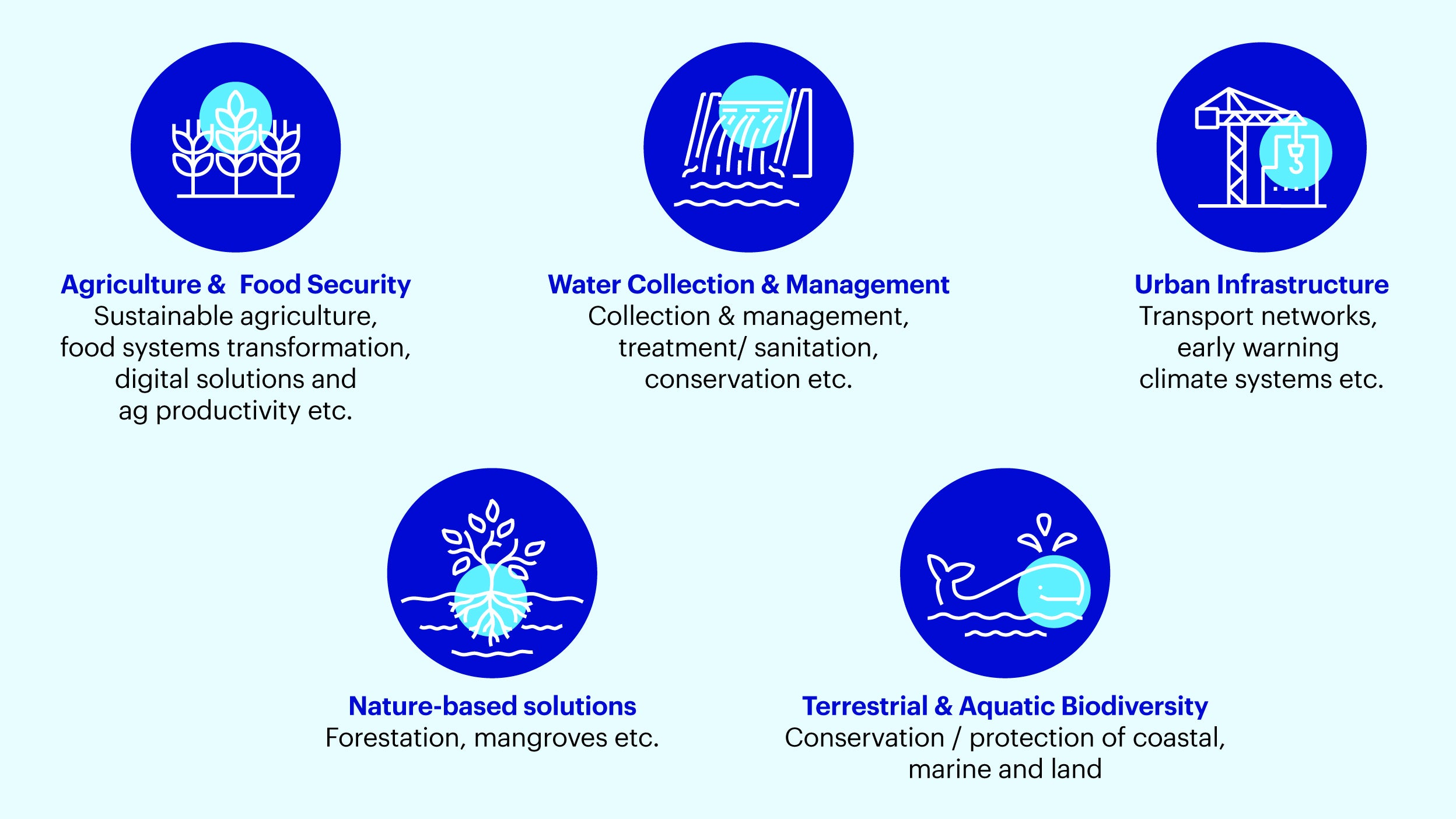

We see a wide range of investment themes within the climate adaptation space, which can concurrently provide multi dividend outcomes across various sustainable development goal (SDG) and social outcomes.

- Agriculture and food security: In our view, the challenge for Asia would be how to strengthen food security to withstand extreme weather while mitigating emissions production from agriculture, water quality related issues and potential biodiversity loss. This theme would also cover the opportunity to incorporate sustainable agricultural practices to build a circular bioeconomy, while helping to tackle rural poverty reduction and improving social well-being. Examples would include using digital solutions, technology to boost productivity, food systems transformation (processing and refrigeration facilities).

- Water: Clean water availability remains a key challenge for urban centers and for agriculture production particularly within the emerging Asia economies (particularly in South Asia). The Asian Development Bank estimates that investment needs for water and sanitation in the region to be an average of $53 billion per annum in Asia up to 203012, with at least one-third of this figure required from the private sector. Projects to help tackle clean water availability include water treatment, sanitation and waste treatment facilities, water conservation and water delivery assets amongst others.

- Infrastructure: In many emerging economies, infrastructure development is ongoing at a fast pace, and it is critical to ensure that the new infrastructure that is built will be climate resilient and incorporate climate risk considerations into the design process. In Asia, $1.7 trillion of infrastructure investment is required annually to 203013. Examples would include transport networks (railway, ports, roads, bridges) and also off-grid renewable energy, early warning climate systems amongst others. These uses can be envisioned by new infrastructure, retrofitting infrastructure and also protective infrastructure.

- Nature-based Solutions (NBS): These will be in areas to protect, sustainably manage or restore natural ecosystem to make the environment more climate resilient. Examples of NBS includes the planting of trees in coastal areas such as mangroves as storm barriers to limit the impact on nearby human population, planting of trees to reduce landslide risks and improve biodiversity as well as concurrently a carbon sink.

- Terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity: As seen in many of the examples and investment themes above, adaptation investing does lend to being more supportive of conservation and protection of coastal, marine and land environments.

Challenges to investing for climate adaptation

Similar to what we covered about impact investing, a couple of challenges stands out in adaptation financing:

- Lack of clear framework and taxonomy: Globally there is yet to be a singular definition of climate adaptation though there have been developments such as Climate Bond Initiative (CBI)’s Climate Resilience Principles or adaptation being included as a potential objective for some regional taxonomies. Within the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) green bond principles, climate adaptation is covered in one of the eligible categories. Effective investing for adaptation outcomes would definitely require clear impact assessment and evaluation frameworks.

- Lack of data: Lack of detailed data disclosures on adaptation metrics follows on from the lack of existing standards and disclosure requirements on adaptation. Especially as many adaptation projects tend to be private issuances, data and impact reporting could be an issue.

- Supply of adaptation financing and projects: Industry figures show that adaptation finance is primarily funded by the public sector. At the same time, supply of quality adaptation projects need to go hand-in-hand with financing. As many of these projects are specific to each region, local expertise and networks are required to identify, assess, and monitor projects.

- Bond labels that we see are used for climate adaptation use of proceeds (Up) include: blue bonds, biodiversity bonds and climate resilience bonds. We have seen the use of these labels within the Asian bond markets currently, such as in China and Japan.

Invesco’s approach to adaptation investing

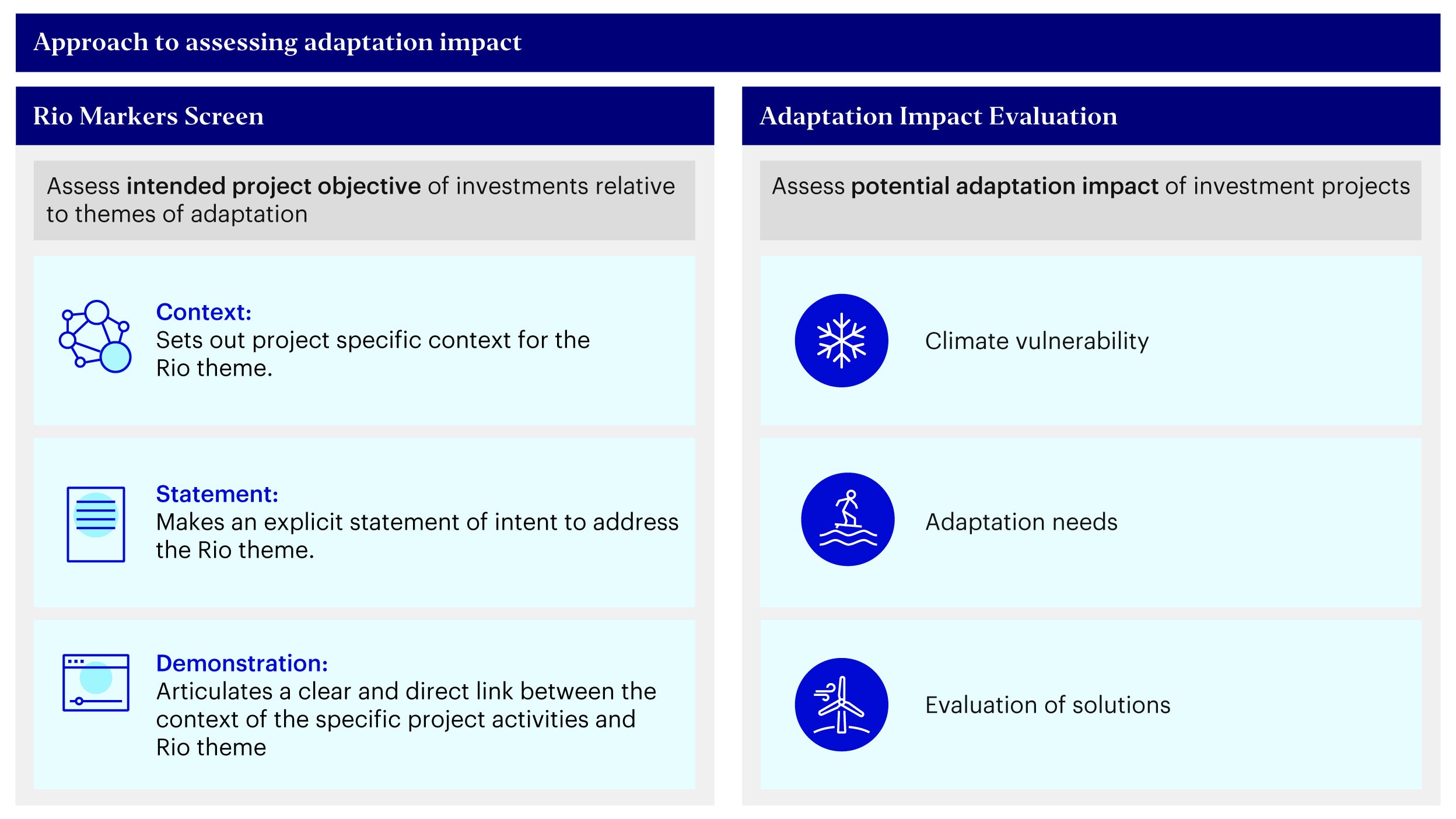

Source: Invesco analysis, for illustrative purposes only.

Given the challenges laid out and the varied investment opportunities, we believe this lends to a proprietary approach by Invesco to evaluate adaptation financing using a combined Rio Markers and Adaptation Impact Evaluation framework. This is part of an ongoing assessment and review when we own the investments in our portfolio, not just at the point of issuance of the instrument. We also believe that adopting an engagement strategy to scale up adaptation financing with both public and private stakeholders is important to mobilize further private sector capital.

- Rio Markers: Developed by the OECD, Rio Markers help to assess intended objectives of a project in question. This includes looking at the project context, objective statement, and linkage to project activities.

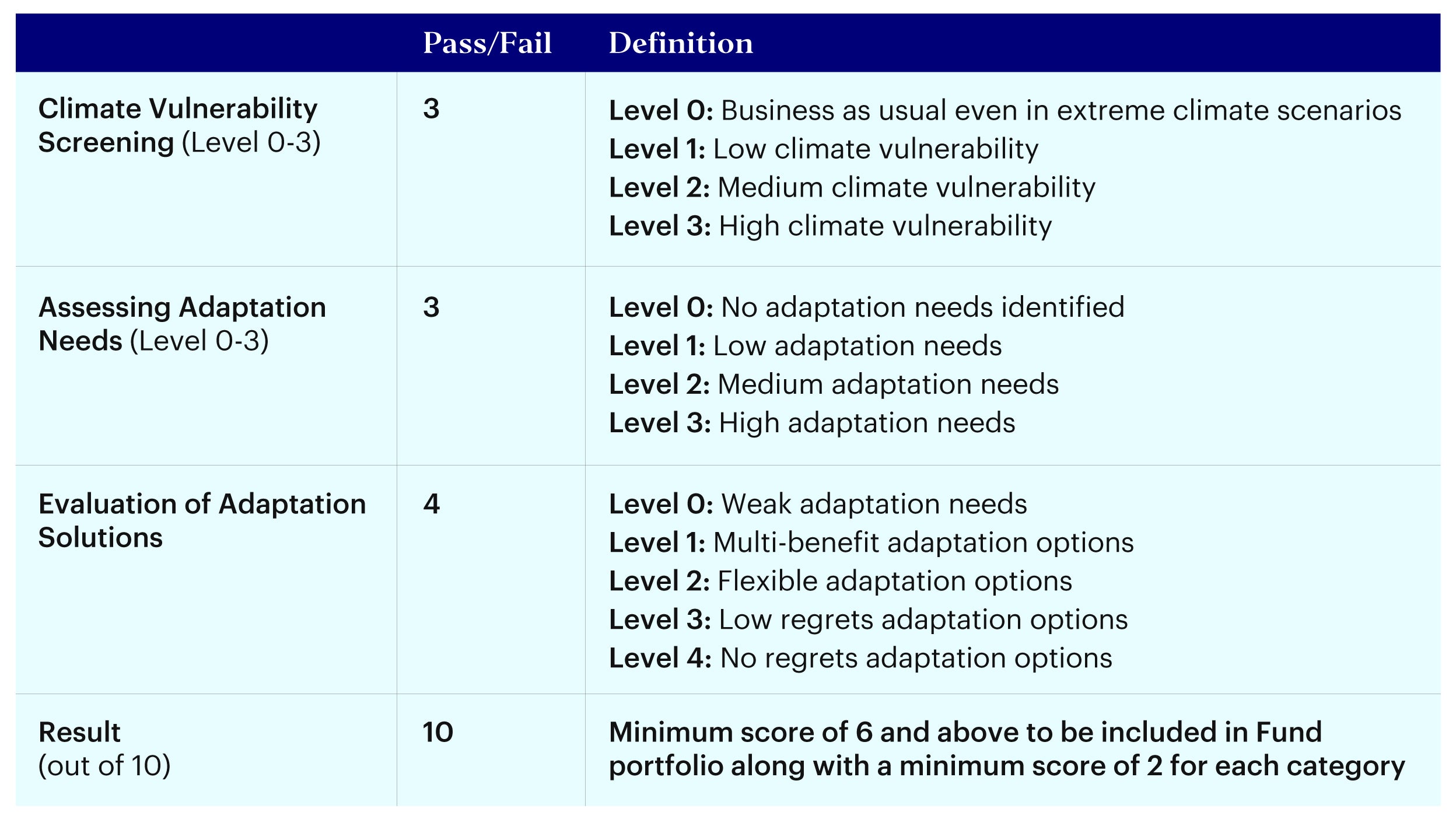

- Climate Adaptation Impact Framework: There are three core pillars we evaluate within our proprietary framework, namely: climate risk screening, assessing adaptation needs and evaluation of adaptation solutions.

Source: Invesco analysis, for illustrative purposes only.

- Climate risk screening: Within climate risk screening, we assess extreme weather risks, alongside the risk of climate events happening. This is based on climate science and modelling wherever available, as well as using data indicators such as GAIN vulnerability score. We also screen for the consequence of climate change in physical risks, transition risks and litigation risks.

- Assessing adaptation needs: When assessing adaptation needs, we focus on target population, region, or ecosystem. In addition, we use data inputs such as GAIN Income Group and GAIN Readiness Score. Lastly, this also includes the magnitude of financing gap for adaptation.

Evaluation of adaptation solutions: An adaptation solution has to lower the consequence of climate change and demonstrate clear cost benefit ratio. Another positive factor when we evaluate would be the commercial viability of the solution. Most pertinently, we also evaluate the proposed impact reporting provided, alongside clear KPIs with monitoring mechanism. External technical expertise applied can be a positive as we assess the execution risk of the solution.

This is accompanied with clear impact reporting on beneficiaries and environmental key performance indicators (KPIs). The bond labels that can be consistent with a climate adaptation objective include blue blonds, climate resilience bonds and biodiversity bonds.

Given the higher physical and socioeconomic impact of climate change in Asia, it is imperative that the climate adaptation financing gap is closed with the mobilization of private capital. Given the lack of a taxonomy, we believe that our proprietary approach using Rio Markers and adaptation impact evaluation provides a suitable approach to direct financing towards the most impactful adaptation projects and assist in capacity building. Lastly, we see that these investment opportunities also yield really strong targeted social outcomes with a triple dividend of improving climate resilience, social impact, and economic development particularly in emerging economies within the Asia-Pacific region.

FOOTNOTES

- 1

-

2

Carbon Brief Guest post: Why avoiding climate change ‘maladaptation’ is vital - Carbon Brief

-

3

UNFCCC COP27 Reaches Breakthrough Agreement on New “Loss and Damage” Fund for Vulnerable Countries | UNFCCC

- 4

-

5

UNEP First draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (cbd.int)

-

6

IPCC WGII p 1476 IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

-

7

IPCC WGII p 1482 IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

-

8

IPCC WGII p 1502 IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

-

9

IPCC WGII p1509 IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

-

10

IPCC WGII p1469 IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

-

11

Climate Policy Initiative Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021 - CPI (climatepolicyinitiative.org)

-

12

Asia’s water security—the glass is still half full, December 2020, https://www.adb.org/news/features/asia-s-water-security-glass-still-half-full#:~:text=As%20AWDO%202020%20describes%2C%20despite,1.2%20billion%20lack%20adequate%20sanitation

-

13

Disaster resilient infrastructure – Unlocking opportunities for Asia and the Pacific, April 2022, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/791151/disaster-resilient-infrastructure-opportunities-asia-pacific.pdf