3D investing: adding a third dimension to traditional investing

Key takeaways

The advent of the modern portfolio theory can be traced back to 1952. Since then, the investment industry has established itself as the purveyor of a broad range of products spanning asset classes, geographies styles and themes. The single fiduciary object is clear: to delivery risk-adjusted returns for clients.

ESG factors are often approached in this two-dimensional landscape of risk and return. There’s large and growing literature from academics seeking a definitive determination as to whether ESG factors contribute to or detract from returns. The evidence to date is inconclusive and may remain so given that a constant or consistent correlation seems unlikely.

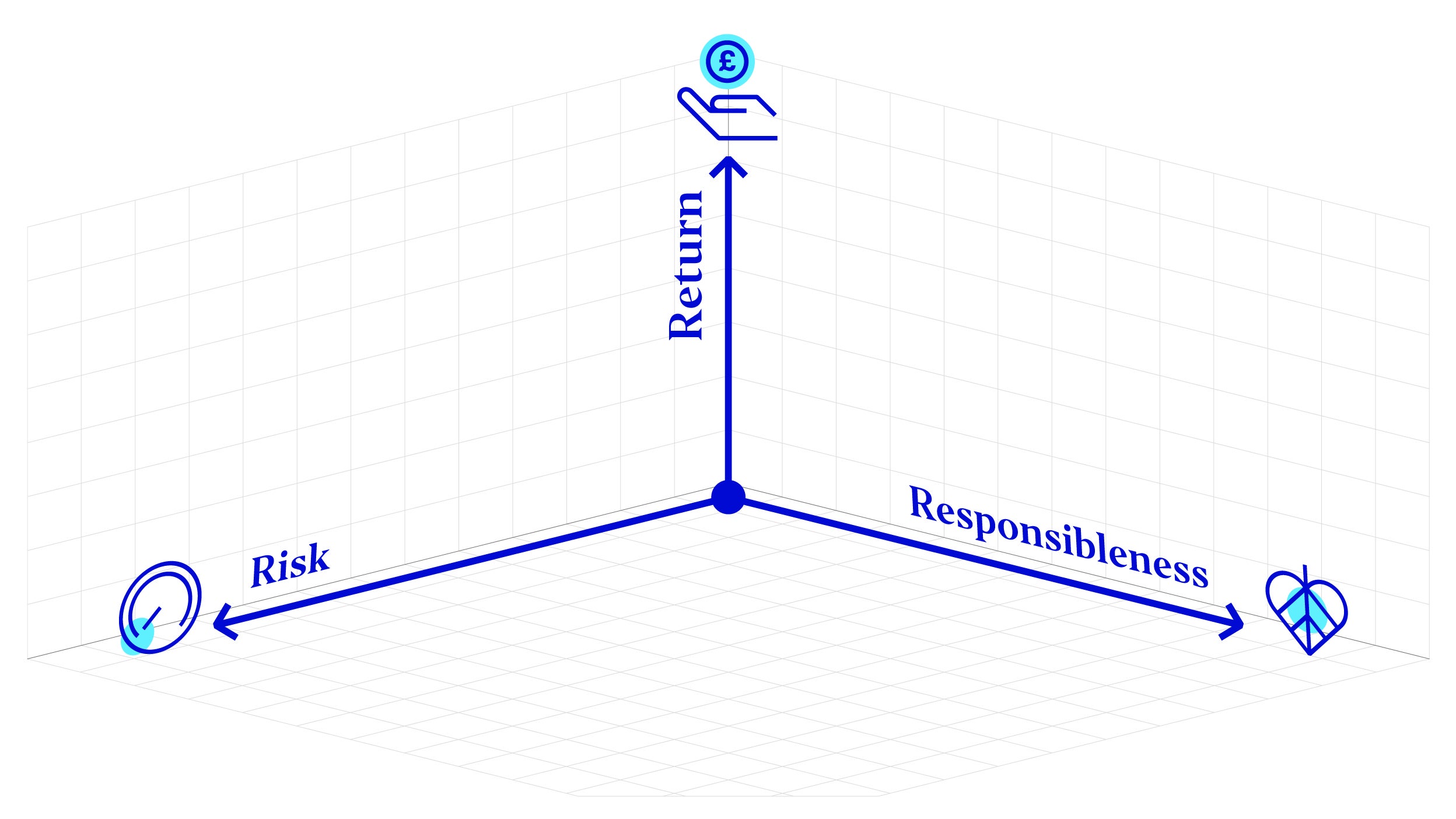

But the key issue is that this debate obscures the realisation that ESG factors are a third dimension for funds and should be measured as such.

When you ask a fund manager for an overview of a fund’s performance, you expect the detail to be clear and unambiguous: ‘show me the return of the fund over a selection of time periods.’ When you ask about the risk of a product, you should receive details in terms of different risk measures – drawdown or volatility. So, when you ask a fund manager about the responsibleness or ESG-ness of a fund, shouldn’t you receive details on ESG?

Though we measure return on a stand-alone basis, we also review it in context. This is normally done by reviewing returns in terms of risk. A fund that delivers the same returns as another but with lower risk is likely to be preferable to clients - traditional 2D investing. In the same vein as risk, ESG can contextualise returns. A fund that delivers the same return but improves gender diversity or lowers carbon emissions is also likely to be preferable. As client preferences are shifting to funds that have ESG objectives, so is the landscape for evaluating performance.

This proposition is not dismissing financial returns or risk though - these remain crucial. The aim is to add a third dimension – responsibleness - to the two dimensions of risk and return that the fund industry has operated on for some time.

While we all know that higher risk should accompany higher return, the reality is that this is neither fixed or in constant correlation. I’m sure the interaction of ESG on risk and return is similarly mercurial. This three-dimensional approach not only enables the review of each axis but importantly how each have interacted with each other and enables greater comparison across funds.

This construct does not argue how ESG factors will impact risk and return, it instead provides an approach to review how each factor has been impacted, allowing for analysis of the reality of outcomes rather than the theoretical potential of whether ESG will or won’t impact returns.

Looking at performance across all three dimensions is a fundamental change and one not well understood. Stephen Horan, Elroy Dimson, Kenneth Blay and I have been working on disentangling fund objectives across this third dimension – responsibility – from those that pertain to return and risk. The findings of this work will be presented in an upcoming research paper.

Seeing in 3D

This 3D evaluation is less relevant for traditional funds because they will maintain the traditional fiduciary duty of financial returns. Fund managers of traditional funds will and should review any factor that might impact the value of an investment. This could be the action of central bankers, the savings rates of consumers or the actions of a CEO. ESG factors are no different, especially because they may impact the value of a security and so should also be in scope of consideration. However, it’s important to understand that investors motivated to analyse ESG factors for possible return benefits are simply active investors pursuing higher returns.

The ESG movement has been so prevalent that many traditional funds are now overselling the fact that they integrate ESG into their security selection processes. This can often confuse clients about whether it’s an ESG fund or a traditional fund. To be clear, any fund that only integrates ESG data is not an ESG fund, it’s a traditional fund reviewing all aspects that might impact the value of their investments.

Investors and fund managers will, over time, increasingly set out their desire and intent as it relates to each of these three constituents – Risk, Return and Responsibleness. We call this R3 and it has the flexibility to allow for the separation of traditional investing objectives and ESG objectives. This is important because conflating return objectives with ESG objectives fails to distinguish between these two types of objectives.

Fiduciary duty

Funds that state an ESG objective have arguably established a fiduciary duty to deliver against that objective, since the premise of fiduciary duty is to deliver in the best interest of the client. Therefore, to the extent the client had stated a clear preference in terms of how their money should be managed, fiduciary duty applies in ensuring delivery against that preference. Put simply, if a fund has a secondary non-financial objective or target – let’s say carbon emissions or gender – then I think it seems reasonable to judge the ability of the fund to deliver against that objective or target.

This is where the ESG investing conundrum lies. Sustainable, Responsible and Impact investment funds are often evaluated through the traditional 2D lens of risk and return. I would argue that ESG funds, with their additional fiduciary duty, should be measured and assessed in 3D, with the inclusion of their ESG credentials being measured separately and in addition to risk and return. All three components are important.

I would add that the obsession with fiduciary duty is misplaced as a lever to push ESG investing. This is because fiduciary duty is about process rather than about outcomes. A fund manager that loses all his clients’ money isn’t necessarily in breach of his fiduciary duty since financial markets are particularly hard to predict. What’s crucial is that there are appropriate and demonstratable processes in place, combined with the correct level of diligence. Successful claims for breach of fiduciary duty have almost always been about the failure to have appropriate processes in place, rather than the actual outcome.

Conclusion

Measuring the non-financial outcomes of a fund needs to be segregated for the sanity of the industry, for the ability to deliver against them, and so that clients can evaluate how a fund has done against them.

Currently, outcomes for ESG investments are often reported through pretty pictures and platitudes that may or may not have any relation to the ESG impact of the investments. There needs to be greater standardisation, greater clarity, and a greater distinction made between financial outcomes and non-financial outcomes offered and achieved by investment products. Without this there will be increasing cynicism that will endanger the growth of this crucial investing trend. Clients are demanding 3D investing and we need to see the world in all these dimensions.